Most of the computer programs we’ll write must deal with numbers in some way. So, it makes perfect sense to start working with the numerical data types, since we’ll use them very often. Let’s dive in and see how we can use these numerical data types in Java!

Java has built in primitive types for various numeric, text and logic values. A variable in Java can refer to either a primitive type or a full fledged object.

Integers

The first data types we’ll learn about in Java are the ones for storing whole numbers. There are actually 4 different types that can perform this task, each with different characteristics.

| Name | Type | Size | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byte | byte |

8 bits | $ -128 $ | $ 127 $ |

| Short | short |

16 bits | $ -32\,768 $ | $ 32\,767 $ |

| Integer | int |

32 bits | $ -2\,147\,483\,648 $ | $ 2\,147\,483\,647 $ |

| Long | long |

64 bits | $ -2^{63} $ | $ 2^{63} - 1 $ |

As we can see, each data type in this list has a different size, and can store numbers within a different range. So, if we know the minimum and maximum values that could possibly be stored in a particular variable, we can use the smallest corresponding data type that can store that value. This would allow us to conserve the amount of memory used in our programs.

However, in practice, most modern computers have more than enough memory available to handle our programs, so this is typically not a concern for most developers. Instead, it is best to use the largest possible data type, to avoid errors in the future as the program is updated and data values may become larger than initially anticipated.

In this program, and most of the code in this book, we’ll typically use the integer, or int data type for all whole numbers. Even though it isn’t the largest data type for storing whole numbers, it is generally large enough. In addition, the int data type is supported universally across many different programming languages, so learning how to use it will make it easier to switch between languages later on.

Floating Points

The next data types we’ll learn about in Java are the ones for storing rational and irrational numbers. There are actually 2 different types that can perform this task, each with different characteristics.

| Name | Type | Size | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Float | float |

32 bits | $ \pm 10^{\pm 38} $ |

| Double | double |

64 bits | $ \pm 10^{\pm 308} $ |

Unlike the data types for whole numbers, it is more difficult to discuss the minimum and maximum values for these data types, as it requires a thorough understanding of how they are stored in binary and interpreted by the processor in a computer. In general, each one can handle large numbers as well as small numbers extremely well.

However, just like scientific notation, the numbers it stores at best can only be as accurate as the number of digits it holds. So, when storing an extremely large number, there will be some rounding error.

In this program, and most of the code in this book, we’ll typically use the Double, or double data type for all decimal numbers.

Using Numbers in Code

Now that we’ve discussed the various data types available in Java, let’s look at how we can actually create variables that can store data in our programs.

Before working with the code examples in the rest of this chapter, we’ll need to add a class declaration and a main method declaration to a file named Types.java. In Codio, you can open it by clicking on the file in the tree to the left. If you don’t recall how to do that, now is a great time to review the material in Chapter 1 before continuing.

Setting up a new file each time is great programming practice!

Declaring

In Java, we can declare a variable using this syntax:

<type> <identifier>;So, to declare a variable of type int named x, we would write:

int x;We can also do the same for each of the types listed above:

byte b;

short s;

int i;

long l;

float f;

double d;As with any other part of our program, we must first declare it before we can use it.

Java has rules about the allowable names with can be used as identifiers, you can find them in the Java Documentation.

By convention, variable names should be descriptive and use camelCase to aid in reading.

Assigning

Once a variable has been declared, we can give it a value using an assignment statement. Assignment uses this syntax:

<destination> = <expression>In that example above, <destination> is the identifier of the variable we’d like to store data in, and <expression> is any valid Java expression that produces a value. It could be a number, another variable, a mathematical operation, or even a method call, which we’ll learn about in a later chapter. The variable we are storing the value in must always be on the left side of the equals = sign.

For example, if we want to store the value

$ 5 $ in an int variable named x, we could write the following:

int x;

x = 5;We can even combine the declaration and assignment statements into a single statement, like this:

int x = 5;The same syntax applies to all of these types in Java:

byte b = 1;

short s = 2;

int i = 3;

long l = 4;

float f = 1.2f;

double d = 3.4;When assigning values from one variable to another using primitive data types, the value is copied in memory. So, changing the value of the first variable would not affect the others, as in this example:

int x = 5;

int y = x;

x = 6;At the end of that code, the value of x is

$ 6 $, but y still contains

$ 5 $. This is important to remember.

See if you can create a variable using each of the six data types listed above in Types.java. What happens when you assign a value at that is too big or too small for the variable’s data type? Can you assign the value from an int variable into a byte variable?

Notice in the code that the float variable f is assigned using the value 1.2f instead of just 1.2. This is because decimal values in Java are interpreted as double values by default, so when assigning a double to a float there is a possible loss of precision that the Java compiler will complain about. To avoid that, we can explicitly state that the value is a float by appending the letter f to it. We won’t see this very often outside of this lesson.

Printing

We can also use the System.out.println and System.out.print methods we learned earlier to output the current value of a variable to the screen. Here’s an example:

int x = 5;

System.out.println(x);Notice that the variable x is not in quotation marks. This way, we’ll be able to print the value stored in the variable x to the screen. If we place it in quotation marks, we’ll just print the letter x instead.

Later, in the project for this chapter, we’ll learn how to combine multiple variables into a single output.

Casting

When writing our programs, sometimes we need to change the data type that a particular value is stored as, especially when we want to store it in a new variable. Ideally, we would construct our programs to avoid this issue, but in the real world we aren’t always so lucky.

To change the data type of a value, we can cast that value to a different data type. To cast a value to a different data type, we put the data type we’d like it to be in parentheses in front of the value.

Let’s look at the example below:

int x = 120;

byte y = x;

System.out.println(y);In this example, we’ve created an int variable x, and stored

$ 120 $ in that variable. We then create a byte variable y, and try to store the value from x into y.

Try to run these examples by placing each one in Types.java and seeing what happens. Does it work? Try it before reading the answers below.

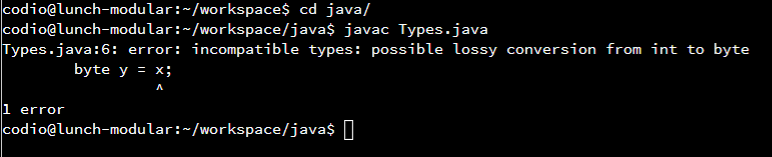

When we try to compile that example, we should get the following compiler error:

Since the int data type is larger than the byte data type, the compiler will give us an error stating that we might lose data when we perform that conversion. Of course, if we reverse the int and byte data types, and try to assign a byte to and int, it will work just fine.

In general, we should try to avoid this problem by redesigning our program to eliminate the need to store a variable in a smaller type, but sometimes it is necessary. To do this, we’ll need to cast the value to the correct data type. Let’s update the example above:

int x = 120;

byte y = (byte) x;

System.out.println(y);In this example, we have added a (byte) in front of the variable x when we are assigning it to y. This tells the compiler that we would like to convert the data type of x to byte before storing it in y. Now, when we try to compile and run this program, it will act as we expect.

However, let’s look at one final example to see why the compiler would warn us about converting to a smaller data type:

int x = 128;

byte y = (byte) x;

System.out.println(y);When we say “cast” we really mean convert. Sometimes this results in a change in the the binary representation. Conversion preserves the semantics (meaning) but over writes the binary. In addition to the “casting” syntax (desired type) value ... (int)2.0, you will be exposed to many ConvertTo() methods later in this course.

Casting nearly always preserves the original binary but may result in gibberish; you lose the meaning.

int x = (int)'2';

// results in x equal to 50 not 2

// '2' binary 00110010

// int value of 00110010 is 50However, “casting” is nearly always used to mean “convert”. It comes from the origins of programming, where languages supported fewer types and the binary had the same semantic meaning across multiple data types.

| type | bytes | binary for the value of 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| byte | 1 | 00000010 | |

| short | 2 | 0000000000000010 | |

| int | 4 | 00000000000000000000000000000010 |

From the above table you can see how casting might work for various sized integer values. Leading “bits” were ignored when casting to a byte-wise smaller type. Leading 0s were added when casting to larger type.

We will use cast and convert interchangeably in this course to mean convert to the desired data type. In Java casting between primitive numeric-types often preserves the semantics (value) of the cast. (int) 2.5 is the integer 2, and (double)-4 is the double -4.0.

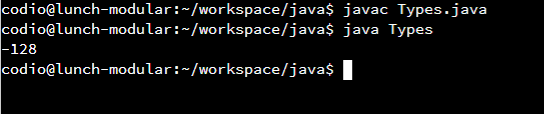

In this example, instead of storing

$ 120 $ in x, we have instead stored

$ 128 $. When we compile and run this program, we get this unexpected output:

We expect it to output $ 128 $, but instead it outputs $ -128 $. That’s strange, isn’t it?

What’s happening is an error known as integer overflow. Since

$ 128 $ is too large to fit in a byte variable, the computer will truncate, or remove, the bits that are at the front of the number that won’t fit. This could cause data to be lost or misinterpreted, which is what happens here.

So, we must always be careful and not try to cast a variable to a smaller data type if it is too large to fit in that data type. This is why the compiler will always warn us when we try to do so, unless we add an explicit cast to our code.

To make things simpler, we typically just use a single data type for whole numbers, and a single data type for decimal numbers. By using the same type consistently throughout our programs, we can avoid many issues related to data types and casting.

As stated above, most of the examples in this book will use the int data type for whole numbers, and the double data type for decimal numbers. These choices are consistent with the majority of official Java code.