Boolean logic contains four operators that perform various actions in a Boolean logic statement. Before we learn about them, let’s take a minute to discuss variables in Boolean logic.

As we covered in a previous chapter, most programming languages support a special data type for storing Boolean values. That data type can only contain one of two values, True or False. So, in a Boolean logic statement, any variable can only be either True or False

For each of the operators below, we’ll see both a truth table and Venn diagram representation of the operation. They both present the same information, but in a slightly different way. In each operation, we’ll see all possible values of the variables present in the statement, and the resulting value of the operation on those variables. Since each variable can only have two values, the possibilities are limited enough that we can show all of them.

In the Venn diagrams below, each circle represents a variable.1 The variables are labeled in the circles on each diagram.

Not $ \neg $

The first, and simplest, Boolean logic operator is the not, or negation, operator. This operator simply negates the given Boolean value, turning True into False and False into True. When written, we use the

$ \neg $ symbol, but most programming languages use an exclamation point ! instead.

Below is a truth table giving the value of $ \neg A $ and $ \neg B $, for all possible values of $ A $ and $ B $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ \neg A $ | $ \neg B $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | T | T |

| F | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T |

| T | T | F | F |

We can also see the operation visually using a Venn diagram. In these drawings, assume each individual variable is True, and the shaded portion shows which parts of the diagram are True for the entire statement.

$ \neg A $

As we can see, if $ A $ is true, then $ \neg A $ represents everything in the diagram outside of the circle labeled $ A $. In fact, it includes the area outside of any circle, which represents the whole universe of items that are neither inside of $ A $ nor $ B $. So, the value of $ \neg A $ is not affected by the value of $ B $ in this instance.

We can also extend this to three variables, as shown in the truth table below. It gives the values of $ \neg A $, $ \neg B $, and $ \neg C $ for all possible values of $ A $, $ B $, and $ C $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ C $ | $ \neg A $ | $ \neg B $ | $ \neg C $ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | F | T | T | T |

| F | F | T | T | T | F |

| F | T | F | T | F | T |

| F | T | T | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | F | T | T |

| T | F | T | F | T | F |

| T | T | F | F | F | T |

| T | T | T | F | F | F |

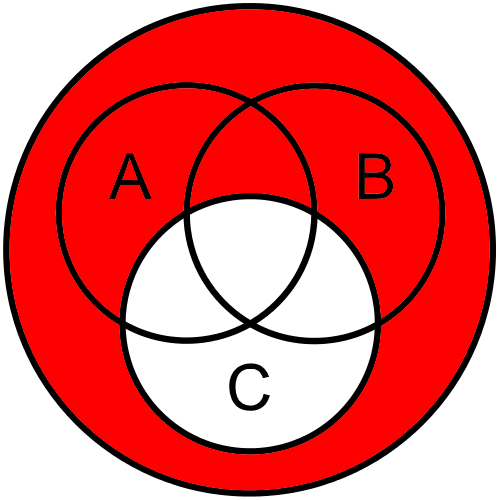

The Venn diagram for this instance is very similar:

$ \neg C $

As we can see, the not operation is very useful when dealing with Boolean values.

And $ \land $

The next Boolean logic operator we’ll cover is the and, or conjunction, operator. This operator works similar to the way we use “and” in our spoken language. If

$ A $ is True, while

$ B $ is also True, then we can say that both

$ A $ and

$ B $ are True. This would be written as

$ A \land B $. Most programming languages use two ampersands && to represent the Boolean and operator, but some languages also include and as a keyword to denote this operator.

Here is a truth table giving the value of $ A \land B $ for all possible values of $ A $ and $ B $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ A \land B $ |

|---|---|---|

| F | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| T | F | F |

| T | T | T |

As we can see, the only time that

$ A \land B $ is True is when both

$ A $ and

$ B $ are True.

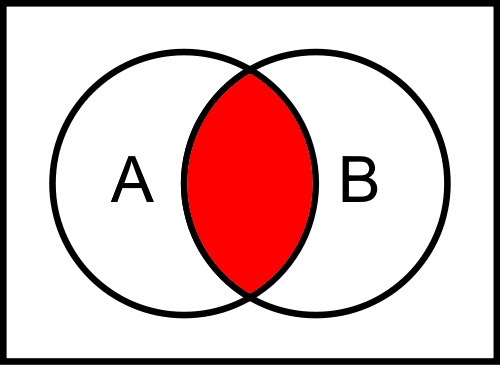

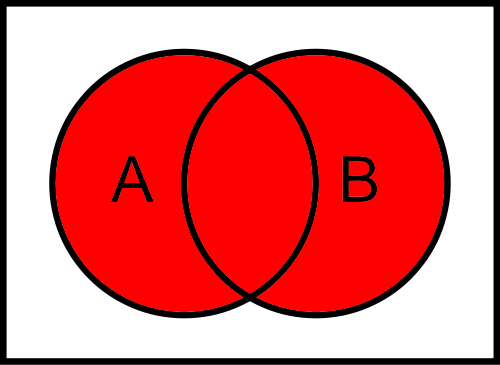

Next, we can look at a Venn Diagram that represents this operation

$ A \land B $

As we can see, only the center of the Venn diagram is shaded, representing the parts of the diagram that are both in $ A $ and $ B $ at the same time.

This operation also easily extends to three variables. This truth table gives the value of $ A \land B \land C $ for all possible values of $ A $, $ B $, and $ C $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ C $ | $ A \land B \land C $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | F | F |

| F | F | T | F |

| F | T | F | F |

| F | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | F |

| T | F | T | F |

| T | T | F | F |

| T | T | T | T |

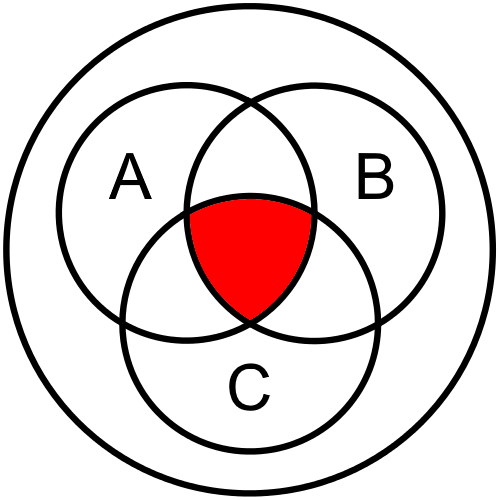

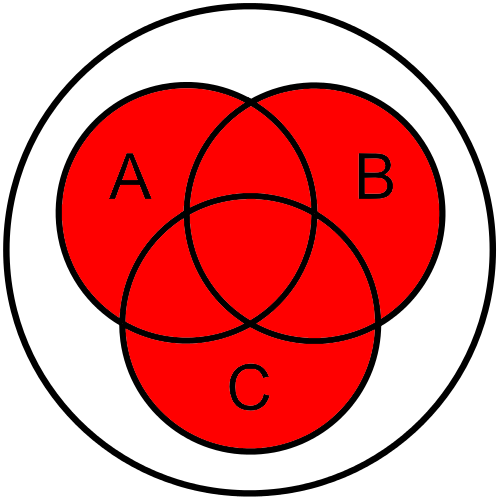

The Venn diagram for this instance is very similar to the one above:

$ A \land B \land C $

Once again, we see that only the very center of the diagram is shaded, as expected.

Or $ \lor $

The third Boolean operator is the or, or disjunction, operator. It is somewhat similar to how we use the word “or” in our spoken language, with a major difference. This operator would be written as

$ A \lor B $. Most programming languages use two vertical pipes || to represent the Boolean or operator, but some languages also include or as a keyword to denote this operator.

Consider ordering food at a restaurant as an example. On the menu, you might see the statement “Soup or Salad” as one of the options for your meal. This means that you must choose either “soup” or “salad” to go with your meal, but usually you aren’t allowed to have both (at least, without paying more).

Now, consider a similar statement,

$ A \lor B $. If either

$ A $ or

$ B $ are True, we would say that

$ A \lor B $ is also True. However, if both

$ A $ and

$ B $ are True, we would also say that

$ A \lor B $ is True. So, the Boolean or operator will return True when both inputs are True, which differs from how we use it in spoken language.

Here is a truth table giving the value of $ A \lor B $ for all possible values of $ A $ and $ B $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ A \lor B $ |

|---|---|---|

| F | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| T | T | T |

As we can see, the only time that

$ A \lor B $ is False is when both

$ A $ and

$ B $ are False. As long as at least one of the values is True, the whole statement is True.

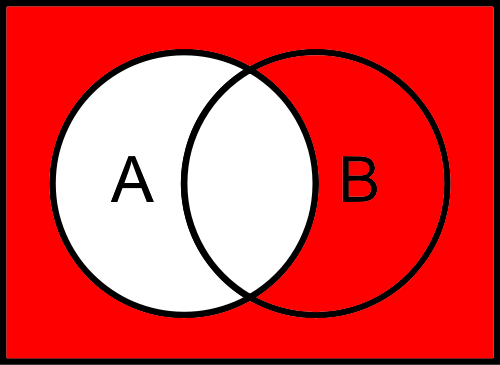

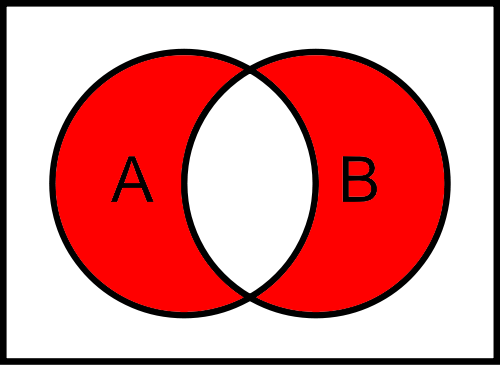

Next, we can look at a Venn Diagram that represents this operation

$ A \lor B $

As we can see, both circles are completely shaded, showing that $ A \lor B $ contains all items in either $ A $ or $ B $, or both $ A $ and $ B $ at the same time.

This operation also easily extends to three variables. This truth table gives the value of $ A \lor B \lor C $ for all possible values of $ A $, $ B $, and $ C $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ C $ | $ A \lor B \lor C $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | F | F |

| F | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T |

| F | T | T | T |

| T | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | T |

| T | T | F | T |

| T | T | T | T |

The Venn diagram for this instance is very similar to the one above:

$ A \lor B \lor C $

Once again, we see that all parts of the Venn diagram are shaded, except for the part outside of all the circles.

Exclusive Or $ \oplus $

The last Boolean operator we’ll cover is exclusive or, or exclusive disjunction. We’ll sometimes see this referred to as xor as well. When written, we use the $ \oplus $ symbol. However, not all programming languages have implemented this operator, so there is no consistently used symbol in programming.

This operator works in the same way that “or” works in our spoken language. Recall the “Soup or Salad” example from earlier. The exclusive or operation is True if only one of the inputs is True. If both inputs are True, the output is False.

Here is a truth table giving the value of $ A \oplus B $ for all possible values of $ A $ and $ B $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ A \oplus B $ |

|---|---|---|

| F | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| T | T | F |

As we can see, the result is True when either

$ A $ or

$ B $ are True, but it is False if both of them are True, or if both of them are False.

As a Venn diagram, it would look like this:

$ A \oplus B $

As we can see, the parts of the diagram in $ A $ and $ B $ are shaded, but the center part, which is in both $ A $ and $ B $, is not shaded.

This operation is most interesting when extended to three variables. This truth table gives the value of $ A \oplus B \oplus C $ for all possible values of $ A $, $ B $, and $ C $.

| $ A $ | $ B $ | $ C $ | $ A \oplus B \oplus C $ |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | F | F | F |

| F | F | T | T |

| F | T | F | T |

| F | T | T | F |

| T | F | F | T |

| T | F | T | F |

| T | T | F | F |

| T | T | T | T |

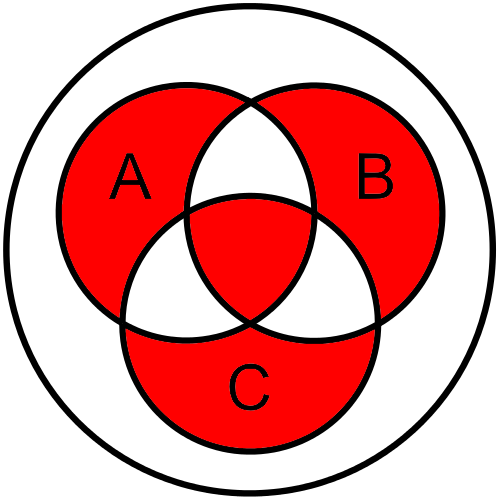

The Venn diagram for this instance is as follows:

$ A \oplus B \oplus C $

In this instance, we see the parts of the diagram representing items that are just in $ A $, $ B $, and $ C $ alone are shaded, as we’d expect. However, we also see the center of the diagram, representing items in $ A \land B \land C $ is also shaded. Interesting, isn’t it? Let’s see if we can break it down.

Just like we hopefully remember from mathematics, when we have multiple operations chained together, we must respect the order of operations. So, we can insert parentheses into the original statement to show how it would actually be calculated:

$ ((A \oplus B) \oplus C) $Now, let’s assume that all three of our variables are True, represented by

$ T $. So, we can reduce the first part as follows:

$$((A \oplus B) \oplus C) $$ $$((T \oplus T) \oplus T) $$ $$(F \oplus T) $$

As we can see, since

$ A $ and

$ B $ are both True, we find that

$ A \oplus B $ is False, as expected. Now, we can continue to reduce the expression:

$$ (F \oplus T) $$ $$ T $$

In this case, since only one of the two operands is True, the result of exclusive or would also be True. Therefore,

$ A \oplus B \oplus C $ is True when all three variables are True. In short, a string of exclusive ors is True if an odd number of the variables are True, and it is False if an even number of variables are True.

Not all languages support an logical exclusive or. Alternate forms are $ ( A \lor B) \land \lnot (A \land B) $ or $ (\lnot A \land B) \lor (A \land \lnot B) $.

At some restaurants, you are given a choice of not just two, but three items to go with your meal. Of course, the intent is for you to choose just one of the three items listed.

However, now that you understand how exclusive or works, you might see how you could get all three items instead of just one! Logic is pretty powerful, isn’t it?

Comparators

Finally, it is worth discussing other operators that can result in a Boolean value. The most important of these operators are the comparators, which compare two values and return a result that is either True or False. We’ve definitely seen these operators before in mathematics, but may not have actually realized that they result in a Boolean value.

Below is a table giving the common comparators used in programming, along with an example of how they might be used:

| Name | Operator | Symbol | True Example |

False Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal | $ = $ | == |

1 == 1 |

1 == 2 |

| Not Equal | $ \neq $ | != |

1 != 2 |

1 != 1 |

| Greater Than | $ > $ | > |

2 > 1 |

1 > 2 |

| Greater Than or Equal To | $ \geq $ | >= |

1 >= 1 |

1 >= 2 |

| Less Than | $ < $ | < |

1 < 2 |

2 < 1 |

| Less Than or Equal To | $ \leq $ | <= |

1 <= 1 |

2 <= 1 |

That covers all of the basic operators and symbols in Boolean logic. On the next page, we’ll learn how to combine them together and create logical statements using the rules of Boolean algebra.

-

The Venn diagrams are adapted from ones found on Wikimedia Commons ↩︎