One of the most powerful features of the conditional constructs we’ve covered so far in this course is the ability to chain them together or nest them within each other to achieve remarkably useful program structures. The ability to use conditional constructs effectively is one of the most powerful skills to develop as a programmer.

Zero, One, Negative One

A great example of the many ways to structure a program using conditional constructs is building a simple program that does three things:

- If

xis less than $ 0 $, output-1 - If

xis equal to $ 0 $, output0 - If

xis greater than $ 0 $, output1

Let’s look at two different ways we could structure this program using the conditional constructs we’ve already learned.

See if you can build each of these examples in a file named Conditionals.java, either in Codio or on your own computer. Doing so is a great way to get additional practice working with conditional constructs.

Don’t forget to add the correct class declaration to the file as well! It is not included in the code examples below.

Chaining If Statements

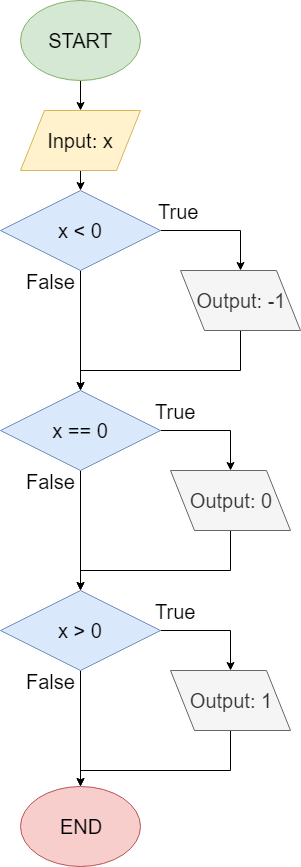

First, we could chain together several if statements to create this program. As a flowchart, the program might look like this:

Here’s one way that program could be written in Java. Once again, we’re just using hard-coded variables for now:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

if (x < 0) {

System.out.println(-1);

}

if (x == 0) {

System.out.println(0);

}

if (x > 0) {

System.out.println(1);

}

}Just like we see in the flowchart, this program contains three if statements chained together, one after another. If we run this program with various inputs, we should see that it produces the expected result.

Nesting If-Else Statements

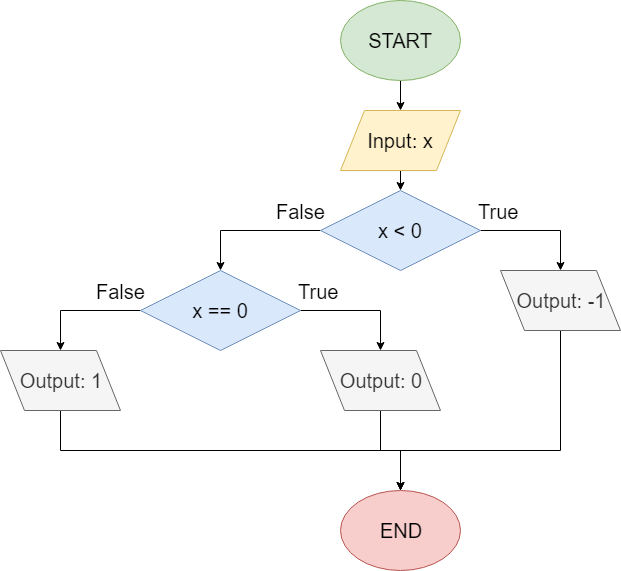

Next, we can achieve the same result using if-else statements. Here’s what that program would look like as as flowchart:

We can also write that program in Java. Here’s one possible way to do it:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

if (x < 0) {

System.out.println(-1);

} else {

if (x == 0) {

System.out.println(0);

} else {

System.out.println(1);

}

}

}In this example, we’ve nested an if-else statement inside of the second block of another if-else statement. So, if the first Boolean expression, x < 0, is true, we’ll output -1 and end the program. However, if it is false, we’ll go into the false branch of the first statement. Then, we’ll see another Boolean expression, x == 0. If that expression is true, we’ll output 0. Otherwise, we’ll output 1. Once again, this program should produce the correct result.

Of course, we could include a third if-else statement, as shown in this example:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

if (x < 0) {

System.out.println(-1);

} else {

if(x == 0){

System.out.println(0);

}else{

if(x > 0){

System.out.println(1);

}else{

//this should never happen

System.out.println("ERROR!");

}

}

}

}As we discussed earlier in this chapter, we can safely infer that x must be greater than

$ 0 $ based on the two previous Boolean expressions. However, what if we’ve made a logic error in our program, and that assumption is not valid? By including the last if-else statement, we can have our program print an error in the unlikely chance that the value of x is not properly handled by any other option.

In fact, here’s how easy it is to cause just that sort of logic error. Consider the following example:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

if (x < -1) {

System.out.println(-1);

} else {

if (x == 0) {

System.out.println(0);

} else {

if (x > 1) {

System.out.println(1);

} else {

//this should never happen

System.out.println("ERROR!");

}

}

}

}Can you spot the logic error in the example above? Try running the code with different values for x and see what happens.

In this example, we’ve updated the Boolean expression in the first if-else statement to x < -1. Similarly, we’ve changed the Boolean expression in the third statement to x > 1. That change seems logical, right?

What if the value of x is exactly

$ 1 $ or

$ -1 $? In that case, it will fail all three logic expressions, and the program will output ERROR! instead. By including the third if-else statement, we can detect logic errors that may not easily be found otherwise. Without that statement, the program would most likely output 1 even when the input is -1, which is clearly a negative number.

So, in many cases, it may be better to include additional if-else statements to explicitly check all possible cases, instead of relying on assumptions and inferences, which may lead to unintended logic errors.

Inline Nesting

Finally, it is acceptable to minimize nested if-else statements if the nested statement is exclusively in the false branch. Here’s an example:

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

if (x < 0) {

System.out.println(-1);

} else if (x == 0) {

System.out.pr intln(0);

} else if (x > 0) {

System.out.println(1);

} else {

//this should never happen

System.out.println("ERROR!");

}

}Many programming languages refer to this structure as an if-else if-else statement. In this program, if the first Boolean expression is false, it immediately moves to the next Boolean expression following the first set of else if keywords. The process continues until one Boolean expression evaluates to true, or the final else keyword is reached. In that case, we know that none of the Boolean expressions evaluated to true, so the final false branch is executed.

While other programming languages include an explicit keyword for else if, Java does not. Instead, we are simply omitting the curly braces that surround the false block on each if-else statement. The Java compiler treats the entire if-else statement contained in that block as a single line, so the curly braces are not explicitly required in this case.

This is the one and only case where it is acceptable to remove those unnecessary curly braces in most Java style guides. Some programmers find this inline structure simpler to read and follow, as it avoids the problem of code being nested several layers deep. Others feel that it is dangerous to remove any explicit curly braces, and prefer the nested structure instead.

It should be obvious that only one branch of an if-else if-else will ever be executed, because the branches are mutually exclusive. It is a excellent practice to always use the if-else if-else structure whenever you know the logic should be exclusive. Consider a simple program we call the “Goldilocks Porridge Temperature Tester”.

if (isTooHot) {

System.out.println("porridge is too hot");

}

if (isTooCold) {

System.out.println("porridge is not hot enough");

}

if (isJustRight) {

System.out.println("porridge is perfect");

}A future reader of the program, unfamiliar with the children’s tale, would see there are 3 boolean variables (isTooHot, isTooCold, isJustRight) and, depending on their values,up to 3-lines might get printed. This is because we cannot safely assume that just one of them will be true. In fact, they could all three be true!

However, if we rewrite the program to use if-else if-else instead of just if-else statements:

if (isTooHot){

System.out.println("porridge is too hot");

}else if (isTooCold) {

System.out.println("porridge is not hot enough");

}else if (isJustRight) {

System.out.println("porridge is perfect");

}the future reader would know that only one line should ever be printed.