A Worked Example

YouTube VideoThis video uses `open(str)` instead of `pathlib` Paths. Most on line sources and examples will use the older style as `pathlib` is fairly recent. The written text will use `pathlib`'s approach.

Now that we’ve seen how to handle working with files in Python, let’s go through an example program to see how we can apply that knowledge to a real program.

Problem Statement

Here’s a problem statement we can use:

Write a driver program in Example.py that accepts three files as command line arguments. The first two represent input files, and the third one represents the desired output file. If there aren’t three arguments provided, either input file is not an existing file, or the output file is an existing directory, print “Invalid Arguments” and exit the program. The output file may be an existing file, since it will be overwritten.

The program should open each input file and read the contents. Each input file will consist of a list of whole numbers, one per line. If there are any errors parsing the contents of either file, the program should print “Invalid Input” and exit. As the input is read, the program should keep track of both the count and sum of all even inputs and odd inputs.

Once all input is read, the program should create the output file and print the following four items, in this order, one per line: number of even inputs, sum of even inputs, number of odd inputs, sum of odd inputs.

Finally, when the program is done, it should simply print “Complete” and exit. Don’t forget to close any open files!

So, let’s break down this problem statement and see if we can build a program to perform this action.

First sketch out the control flow, where and what kind of loops you want to use, what variables you’ll create and which modules you will need.

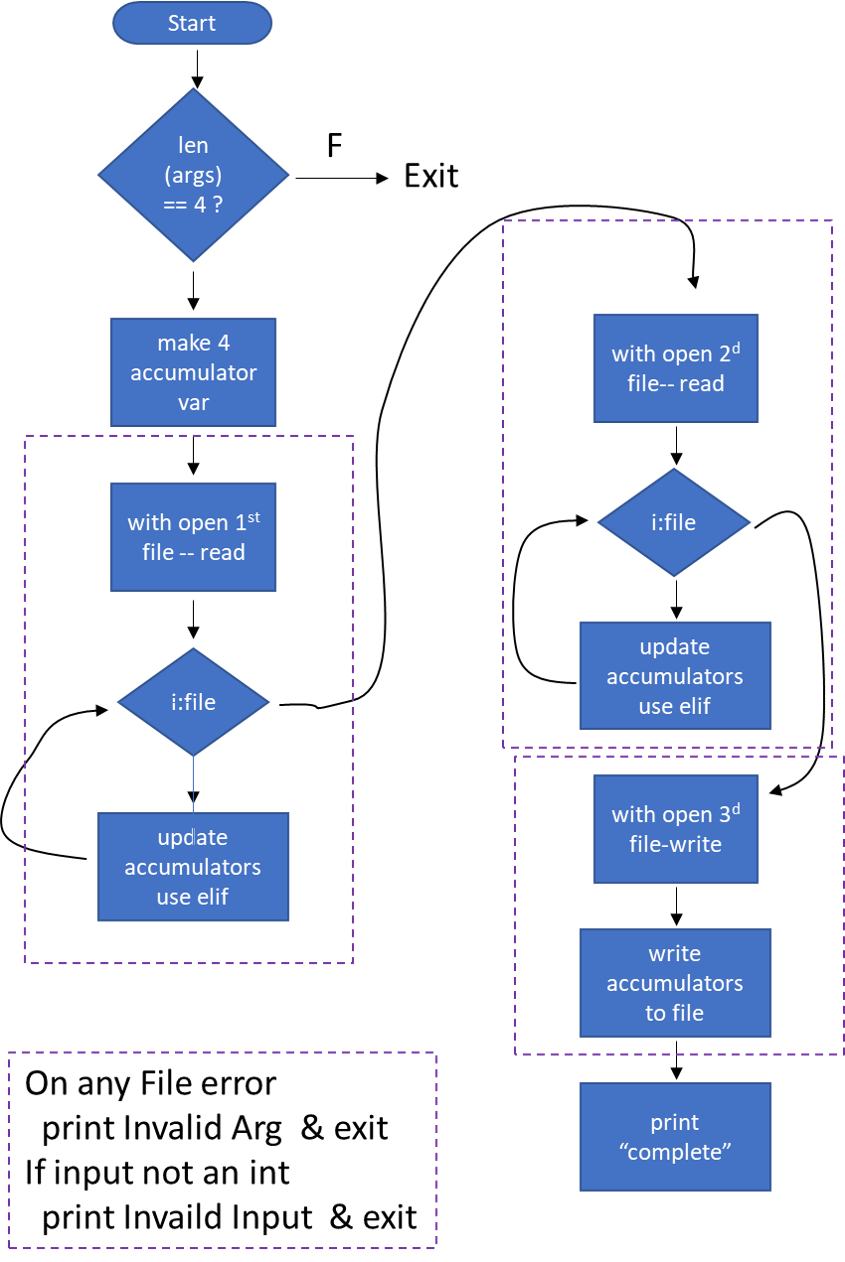

Above is an example sketch for this problem. It does not contain all the details but does give a guide on how the program might to go. Notice how the flow chart abstracts away from the class structure – for an OOP driver program it is detail which is unnecessary to understanding the program flow.

Parsing Arguments

Let’s start programming by parsing the command line arguments. First, we’ll want to make sure there are exactly three arguments. This is probably best done using an If statement, since it makes the code a bit simpler to read than if we would use a Try-Except statement. However, either approach will work.

import sys

from pathlib import Path

class Example:

@classmethod

def main(cls, args):

if len(args) != 4:

print("Invalid Arguments")

return # retruning from main exits the program

if __name___ == "__main__":

Example.main(sys.argv)Don’t forget that sys.argv includes the name of the program, so we’ll really need to make sure that there are 4 arguments in total.

In general, you should check for detectable errors rather than handling them with try-except blocks.

For example, the code snippet above could be skipped and an IndexOutOfBoundsError caught later when access to a missing argument is attempted. But exceptions and exception handlers are many times slower than regular conditional comparison when they are thrown.

Additionally, the logic of the IF statements is more clear–it does not require a reader to be familiar with the exceptions which your code can throw then scanning “except” blocks to see which ones are handled.

An exception to this “Look Before You Leap” approach is type checking a variable before using it; more on this in the methods chapter.

Next, we’ll need to check and make sure that each of the first two arguments is a valid file that we can open. Since we intend to open them anyway, let’s just use a Try-Except statement containing a With statement:

in_file1 = Path(args[1])

in_file2 = Path(args[2])

out_file1 = Path(args[3])

try:

if not in_file1.is_file() or not in_file2.is_file():

print("Invalid Arguments")

return

with in_file1.open('r') as scanner1, in_file2.open('r') as scanner2, out_file1.open("w") as writer:

# -=-=-=-=- MORE CODE GOES HERE -=-=-=-=-

except IOError as e:

print("Invalid Arguments")

return

# -=-=-=-=- MORE EXCEPTIONS GO HERE -=-=-=-=- There are a few new things in this code that we haven’t seen before:

- We can include multiple variables in a With statement by simply separating them with a comma

,. - Since we aren’t worrying about reading input from

sys.stdin, we can just open our files directly in the With statement. Actually, this makes the code very straightforward. - Recall that the

sys.argvvariable is actually a list, so we can access additional command line arguments by simply using different list indices. We haven’t done that yet, but it should make sense.

Now that we’ve confirmed that we can open each file, we can start coding the program’s logic. For the rest of this example, we’ll look at a smaller portion of the code. That code can be placed where the MORE CODE GOES HERE comment is in the skeleton above. We’ll also need to handle a few more exceptions, which can be added where the MORE EXCEPTIONS GO HERE comment is above.

Logic

The program’s logic should be pretty straightforward. First, we’ll need to create loops to read input from each input file:

Notice that we are using two separate For loops here. Since we are dealing with two different input files that are unrelated, this is the simplest way to go.

Next, we can parse the input to an integer, and then determine if it is even or odd:

for line in scanner1:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

# even

else:

# odd

for line in scanner2:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

# even

else:

# oddNotice that we are using two separate For loops here. Since we are dealing with two different input files that are unrelated, this is the simplest way to go.

Next, we can parse the input to an integer, and then determine if it is even or odd:

Finally, we can add a few state variables to keep track of how many of each type we’ve had, and their sum as well:

countEven = 0

countOdd = 0

sumEven = 0

sumOdd = 0

for line in scanner1:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

countEven += 1

sumEven += input

else:

countOdd += 1

sumOdd += input

for line in scanner2:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

countEven += 1

sumEven += input

else:

countOdd += 1

sumOdd += inputExceptions

In the new code above, we are converting strings to integers, which could result in a ValueError. So, we’ll need to add one more except block to the Try-Except statement in the skeleton at the top of this page:

except ValueError as e:

print("Invalid Input")That will handle any problems with the input files themselves.

Printing Output

Finally, we can simply print our four variables to the output file:

countEven = 0

countOdd = 0

sumEven = 0

sumOdd = 0

for line in scanner1:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

countEven += 1

sumEven += input

else:

countOdd += 1

sumOdd += input

for line in scanner2:

line = line.strip()

input = int(line)

if input % 2 == 0:

countEven += 1

sumEven += input

else:

countOdd += 1

sumOdd += input

writer.write("{}\n".format(countEven))

writer.write("{}\n".format(sumEven))

writer.write("{}\n".format(countOdd))

writer.write("{}\n".format(sumOdd))

print("Complete")The four lines at the end should be pretty self-explanatory. We can simply print each number, but we’ll need to convert them to a string first. The simplest way to do that is to use the .format() method to create a formatted string. We’ll also need to remember to print a newline between each of them using the \n character. Of course, we also need to print Complete once we are finished!

Testing

Once we’ve completed the code, we can use the button below to test it and see if it works. Don’t forget to open the example.pregrade.log.txt file that it creates to see detailed feedback from your program.

This content is presented in the course directly through Codio. Any references to interactive portions are only relevant for that interface. This content is included here as reference only.