Instantiation

YouTube VideoThe video above doesn’t show the correct code slides. You can find those slides by clicking the Video Materials link above, and then the Slides link at the top of that page. We’re working on re-recording this video.

Once we have created our class definition, complete with attributes and methods, we can then use those classes in our programs. To create an actual object based on our class that we can store in a variable, we use a process called instantiation.

Instantiation

To instantiate an object in Java, we use the new keyword, and basically call the name of the class like a function:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

new Student();

}

}Of course, that will create a Student object, but it won’t store it anywhere. To store that object, we can create a new variable using the Student data type, and then assign the Student object we created to that variable:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Student jane = new Student();

}

}This will create a new Student object, and then store it in a variable of type Student named jane. While this may seem a bit confusing at first, it is very similar to how we’ve already been working with variables of types like int and double.

Accessing Attributes

Once we’ve created a new object, we can access the attributes and methods of that object, as defined in the class from which it is created.

For example, to access the name attribute in the object stored in jane, we could use:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Student jane = new Student();

jane.name;

}

}Java uses what is called dot notation to access attributes and methods within a class. So, we start with an object created from that class and stored in a variable, and then use a period or dot . directly after the variable name followed by the attribute or method we’d like to access. Therefore, we can easily access all of the attributes in Student using this notation:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Student jane = new Student();

jane.name;

jane.age;

jane.student_id;

jane.credits;

jane.gpa;

}

}We can then treat each of these attributes just like any normal variable, allowing us to use or change the value stored in it:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Student jane = new Student();

jane.name = "Jane";

jane.age = jane.age + 15;

jane.student_id = "123" + "456";

jane.credits = 45

jane.gpa = jane.gpa - 1.1;

System.out.println(jane.name + ": " + jane.student_id);

}

}Accessing Methods

We can use a similar syntax to access the methods in the Student object stored in jane:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Student jane = new Student();

jane.birthday();

jane.grade(4, 12);

}

}Try It

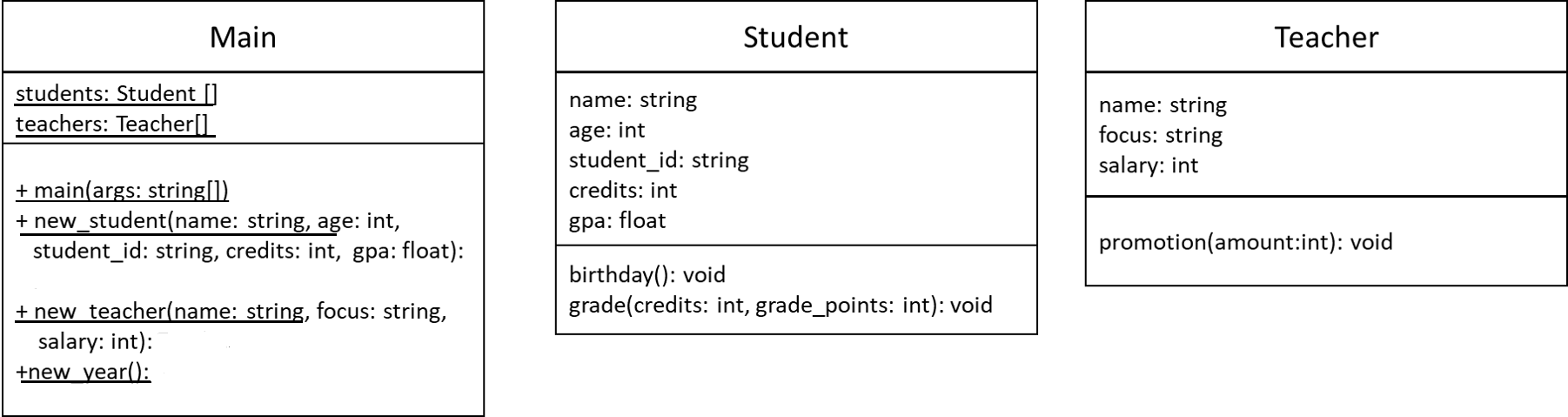

Let’s see if we can use what we’ve learned to instantiate a new student and teacher object in our Main class. First, let’s look at the UML diagram once again:

In that diagram, we see that the Main class should include a method called new_student(), which accepts several parameters corresponding to the attributes in Student. That method should also return an object of type Student. Similarly, there is a method called new_teacher() that does the same for the Teacher class.

So, let’s implement the new_teacher() method and see what it would look like:

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

// more code here

}

static Teacher new_teacher(String name, String focus, int salary){

Teacher someTeacher = new Teacher();

someTeacher.name = name;

someTeacher.focus = focus;

someTeacher.salary = salary;

return someTeacher;

}

}Since we are writing this method in our Main class, we’ll use the static keyword here. We’ll discuss why we need that keyword later in this chapter. Next, we include the Teacher data type as the return data type for this function, since we want to return an object using the type Teacher. Following that, we have our list of parameters, as always.

Inside the function, we instantiate a new Teacher object, storing it in a variable named someTeacher. We must be careful to use a variable name that is not the same as the name of the class Teacher, since that is now the name of a data type and therefore cannot be used as anything else.

Then, we set the attributes in someTeacher to the values provided as arguments to the function. Finally, once we are done, we can return the someTeacher variable for use elsewhere.

Let’s fill in both the new_teacher() and new_student() methods in the Main class now.

In many code examples, it is very common to see variable names match the type of object that they store. For example, we could use the following code to create both a Teacher and Student object, storing them in teacher and student, respectively:

Teacher teacher = new Teacher();

Student student = new Student();This is allowed in Java, since both data type names and variable identifiers are case-sensitive. Therefore, Teacher and teacher can refer to two different things. For some developers, this becomes very intuitive. In fact, we’ve used it several times in this course for the Scanner objects we use to read files.

However, many other developers struggle due to the fact that these languages are case-sensitive. It is very easy to either accidentally capitalize a variable or forget to capitalize the name of a class.

So, in this course, we generally won’t have variable names that match class names in our examples. You are welcome to do so in your own code, but make sure you are careful with your capitalization!