Object-oriented programming allows us to represent items from the real world in our code: we use a class as a general description of each type of item, and then we can instantiate objects based on that class to represent specific items in the world.

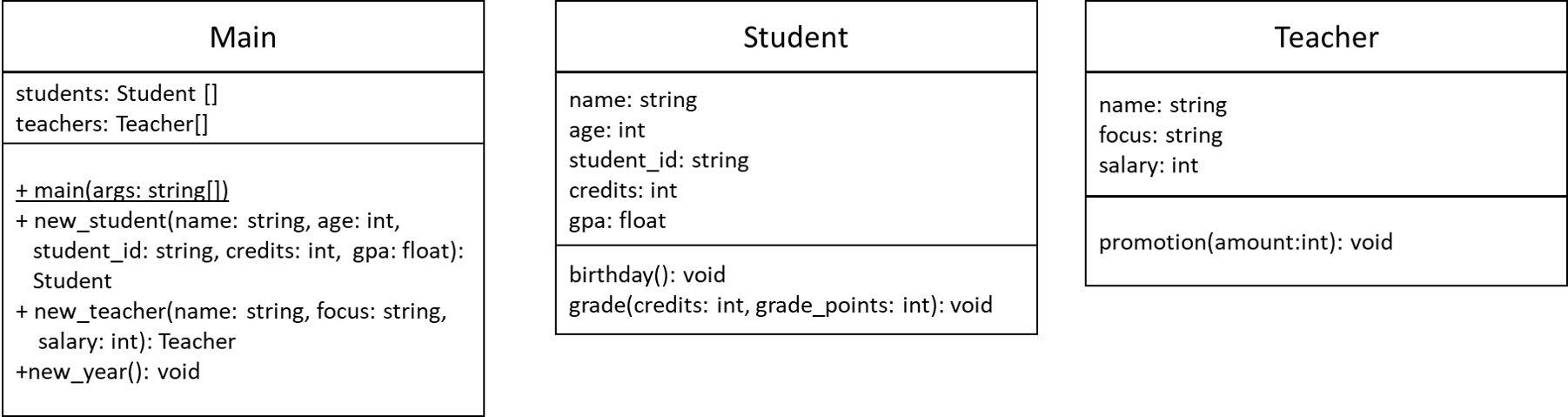

A classic example is to consider writing a computer program to represent a school, with students and teachers represented in code as separate classes. As we can see in the diagram above, both students and teachers can have attributes and methods that help describe the information and behaviors associated with that type of item.

However, this really doesn’t give us the whole picture. For starters, we know that both students and teachers are people, and so they share many of the same features common to all people (name, age, birthday, etc.). Similarly, they can perform many of the same actions.

Of course, we could just add those shared attributes and methods to each class, as we did with the name attribute in the example above. However, hopefully by now our programming instincts tell us that this solution violates the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) mantra, since we’ll have multiple copies of the same code in each class1. If we add an additional class to represent a school administrator, we’ll have to copy all of that code to the new class, making it even more complicated.

This is where we can take our inspiration from the biological system of classification—what if we were able to create a class containing the items that students and teachers have in common?

-

“Sharing attributes” by itself is not a good justification for using inheritance. The real-world objects or concepts should be related in some fashion. ↩︎