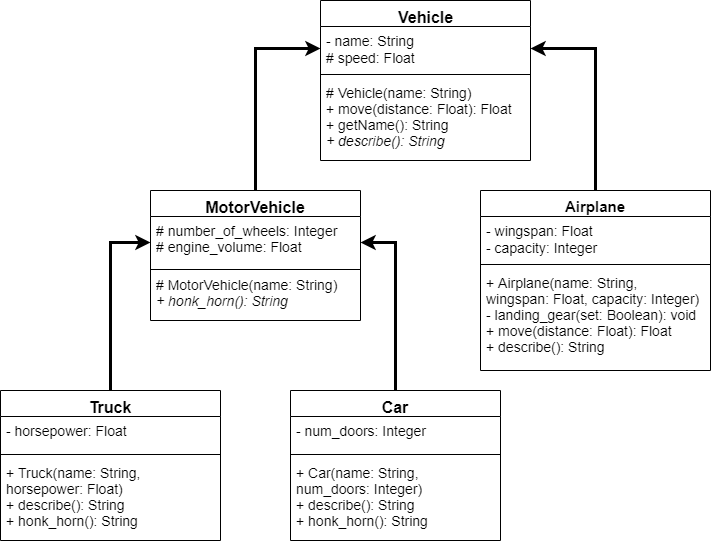

Now that we’ve created some classes that follow different inheritance relationships, let’s explore how we can use those relationships to change some methods in each class through the use of method overriding.

Vehicle Class

First, let’s look at a couple of methods in the Vehicle class, the move() and describe() methods. As we might recall, the describe() method is an abstract method since it is in italicized text in the UML diagram. We’ll discuss how to build an abstract method later in this chapter, but for now we’ll just implement it as a normal method that does nothing. Likewise, we haven’t discussed what a hash symbol # means in front of the speed attribute or the constructor, so we’ll just make them public for now.

public class Vehicle{

private String name;

public double speed;

public String getName(){ return this.name; }

public Vehicle(String name){

this.name = name;

this.speed = 1.0;

}

public double move(double distance){

System.out.println("Moving");

return distance / this.speed;

}

public String describe(){

return "";

}

}That’s a very simple implementation of the Vehicle class. The move() method simply accepts a distance to move as a floating point number, and then divides that by the speed of the vehicle to get the time it takes to go that distance. For the default vehicle, we’ll assume that it moves at a speed of 1.0.

Inheritance and Constructors

Now that we’ve created some methods in the Vehicle class, let’s go back to the Airplane class and see how we can build it. First, we’ll need to add the attributes and the constructor for this class:

public class Airplane extends Vehicle{

private double wingspan;

private int capacity;

public Airplane(String name, double wingspan, int capacity){

this.name = name;

this.wingspan = wingspan;

this.capacity = capacity;

}

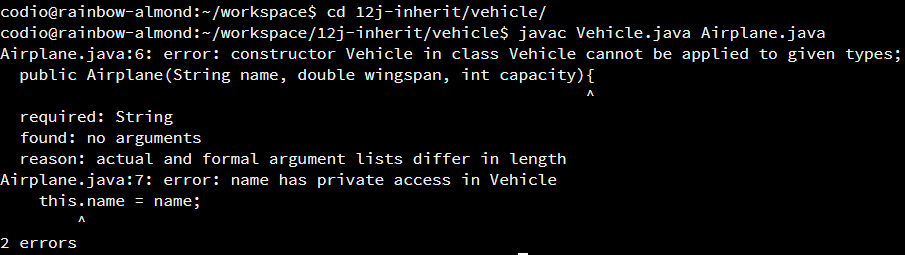

}Before we go any further, let’s stop there and compile this code to make sure that it works. Recall that we’ll need to manually run the compiler from the terminal and include both of these files in the compiler command. So, to do that, we can open the terminal in Codio and use the following two commands to open the directory containing these files and then compile them:

cd ~/workspace/12j-inherit/vehicle

javac Vehicle.java Airplane.javaWhen we do that, we’ll get some errors as shown in this screenshot:

There are actually two errors here. Let’s talk about the second error first. It says that the name attribute in the Vehicle class is private, so we can’t access it from Airplane. This may seem strange, since Airplane is inheriting from Vehicle, but in Java, the private keyword also prevents any child classes from accessing that data.

This actually makes sense if we think about it. For example, consider a class containing private data that we’d like to access. We could just create our own class that inherits from that class, and then we’d have direct access to all those private attributes and methods. Sounds like a pretty bad security flaw, right? That’s why Java enforces the rule that any private attribute cannot be accessed by child classes. Later in this chapter, we’ll learn about another security modifier keyword that allows child classes to access these variables.

So, to set the value of the name attribute, we’ll need to somehow provide that value to the constructor of the Vehicle class. However, the first error addresses that problem directly, so let’s look at it and see how the solution to that error fixes both of these problems.

The first error is telling us that we cannot create an instance of the Vehicle class because we didn’t provide the required parameter for the constructor. But wait, why is it trying to create a Vehicle object? Doesn’t this constructor just instantiate an Airplane object?

One of the major things to recall when inheriting from a class is that each object instantiated from the child class is also an object of the parent class. We can think of it like the child object contains an instance of the parent object. Because of that, when we try to create an instance of the child class, or Airplane in this example, that constructor must also be able to call the constructor for the parent class, or Vehicle.

We run into a snag, however, because we’ve provided a constructor in Vehicle that requires an argument. In that case, we must provide an argument to the constructor for Vehicle in order to instantiate that object, since the default constructor is no longer available. How can we do that?

Thankfully, there is a quick an easy way to handle this in Java. Inside of our constructor, we can use the special method super() to call the parent class’s constructor. We can provide any needed arguments to that method call, which are then provided to the constructor in the parent class. So, let’s update our constructor to use a call to super():

public class Airplane extends Vehicle{

private double wingspan;

private int capacity;

public Airplane(String name, double wingspan, int capacity){

super(name);

this.wingspan = wingspan;

this.capacity = capacity;

}

}Now, inside of the constructor for Airplane, we have added the line super(name), which calls the constructor of the parent class Vehicle, providing name as the argument for the String parameter. This will resolve both of our errors.

It is important to note, however, that the call to the parent class’s constructor using super() must be the first line inside of this constructor, before any other code. The Java compiler will helpfully enforce this restriction, providing us with a helpful error if we forget.

Method Overriding

Finally, we can explore how to override a method in our child class. In fact, it is as simple as providing a method declaration that uses the same method signature as the original method. A method signature in programming describes the method name, return type, and type and order of parameters defined in the function. So, we can override the move() and describe() methods in Airplane using code similar to the following:

public class Airplane extends Vehicle{

private double wingspan;

private int capacity;

public Airplane(String name, double wingspan, int capacity){

super(name);

this.wingspan = wingspan;

this.capacity = capacity;

}

public void landing_gear(boolean set){

if(set){

System.out.println("Landing gear down");

}else{

System.out.println("Landing gear up");

}

}

@Override

public double move(double distance){

this.landing_gear(false);

System.out.println("Moving");

this.landing_gear(true);

return distance / this.speed;

}

@Override

public String describe(){

return String.format("I am an airplane with a wingspan of %f and capacity %d", this.wingspan, this.capacity);

}

}In this code, we see that we have included method declarations for both move() and describe() that use the exact same method signatures as the ones declared in Vehicle. Also, since we are overriding a method from a parent class, we must also use the @Override method decorator above each method. This tells the Java compiler that we intend to override a method with this code, and it will make sure that we’ve done it correctly or give us errors when we try to compile the code.

Calling Overridden Methods

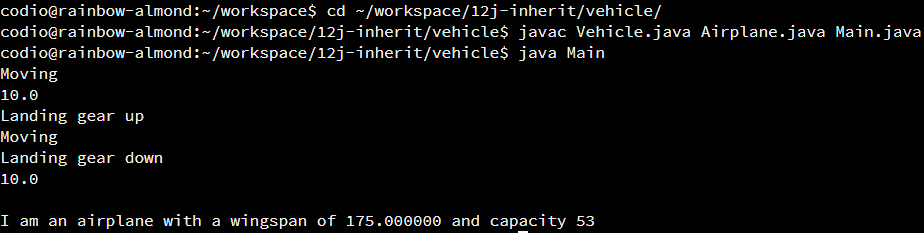

To really understand how this works, let’s look at a quick main() method that explores how each of these work.

public class Main{

public static void main(String[] args){

Vehicle vehicle = new Vehicle("Boat");

Airplane airplane = new Airplane("Plane", 175, 53);

System.out.println(vehicle.move(10));

System.out.println(airplane.move(10));

System.out.println(vehicle.describe());

System.out.println(airplane.describe());

}

}This code will simply call each method, printing whatever values are returned by the methods themselves. We must also remember that some of the methods may also print information, so we’ll see that output before we see the return value printed.

To compile and run this code, we can use these commands:

cd ~/workspace/12j-inherit/vehicle

javac Vehicle.java Airplane.java Main.java

java Mainand we should see the following output:

In this screenshot, we can see that calling the move() method on the Vehicle object just prints the message “Moving”, while calling it on the Airplane object causes the messages about landing gear to be printed as well. This shows that our Airplane object is using the code from the overridden move() method correctly.

In a later part of this chapter, we’ll discuss polymorphism and how overridden methods have a major impact on the functionality of objects stored in that way.

Try it!

Let’s see if we can do the same for the overridden methods in the Truck and Car classes. First, we’ll start with this code for the MotorVehicle class:

public class MotorVehicle extends Vehicle{

public int number_of_wheels;

public double engine_volume;

public MotorVehicle(String name){

super(name);

this.number_of_wheels = 2;

this.engine_volume = 125;

}

public String honk_horn(){

return "";

}

}See if you can complete the code for the Truck and Car classes to do the following:

Truck.describe()should return “I’m a big semi truck hauling cargo”Truck.honk_horn()should return “Honk”Car.describe()should return either “I’m a sedan” if it has 4 doors, “I’m a coupe” if it has 2 doors, or “I’m different” if it has any other number of doorsCar.honk_horn()should return “Beep”

You’ll also need to write the constructors for each class. Inside the constructor, you should store the parameters provided to the appropriate attributes.