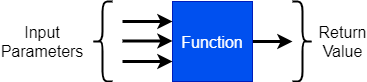

Functions are small pieces of reusable code that allow you to divide complex programs into smaller subprograms. Ideally, functions perform a single task and return a single value. (It should be noted that some programming languages allow for procedures, which are similar to functions but return no values. Except for the return value, it is safe to group them with functions in our discussion below.)

Functions can be thought of as black boxes. When we talk about black boxes we mean that users cannot look inside the box to see how it actually works. A good example of a black box is a soda machine. We all use them and know how to operate them, but very few of actually know how they work inside. Nor do we really want to know. We are happy to simply use them machine and have it give a nice cold soda when we are thirst!

Calling Functions

To be able to reuse functions easily, it is important to define what a function does and how it should be called.

Before we can call a function, we must know the function’s signature. A function’s signature includes the following.

- The name of the function.

- The parameters (data) that must be provided for the function to perform its task.

- The type of result the function returns.

While a signature will allow us to actually call the function in code. Of course to use functions effectively, we must also know exactly what the function is supposed to do. We will talk more about how we do this in the next module on programming by contract. For now we can assume that we just have a good description of what the function does.

While we do not need to know exactly how a function actually performs its task, the algorithm used to implement the function is vitally important as well. We will spend a significant amount of time in this course designing such algorithms.

Executing Functions

The lifecycle of a function is as follows.

- A program (or another function) calls the function.

- The function executes until it is complete.

- The function returns to the calling program.

When the function is called, the arguments, or actual parameters, are copied to the function’s formal parameters and program execution jumps from the “call” statement to the function. When the function finishes execution, execution resumes at the statement following the “call” statement.

In general, parameters are passed to functions by value, which means that the value of the calling program’s actual parameter is copied into the function’s formal parameter. This allows the function to modify the value of the formal parameter without affecting the actual parameter in the calling program.

However, when passing complex data structures such as objects, the parameters are passed by reference instead of by value. In this case, a pointer to the parameter is passed instead of a copy of the parameter value. By passing a pointer to the parameter, this allows the function to actually make changes to the calling program’s actual parameter.