Stacks are useful in many applications. Classic real-world software that uses stacks includes the undo feature in a text editor, or the forward and back features of web browsers. In a text editor, each user action is pushed onto the stack as it is performed. Then, if the user wants to undo an action, the text editor simply pops the stack to get the last action performed, and then undoes the action. The redo command can be implemented as a second stack. In this case, when actions are popped from the stack in order to undo them, they are pushed onto the redo stack.

Maze Explorer

Another example is a maze exploration application. In this application, we are given a maze, a starting location, and an ending location. Our first goal is to find a path from the start location to the end location. Once we’ve arrived at the end location, our goal becomes returning to the start location in the most direct manner.

We can do this simply with a stack. We will have to search the maze to find the path from the starting location to the ending location. Each time we take a step forward, we push that move onto a stack. If we run into a dead end, we can simply retrace our steps by popping moves off the list and looking for an alternative path. Once we reach the end state, we will have our path stored in the stack. At this point it becomes easy to follow our path backward by popping each move off the top of the stack and performing it. There is no searching involved.

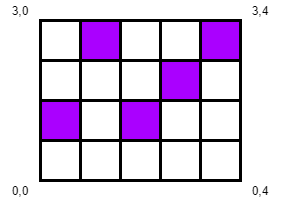

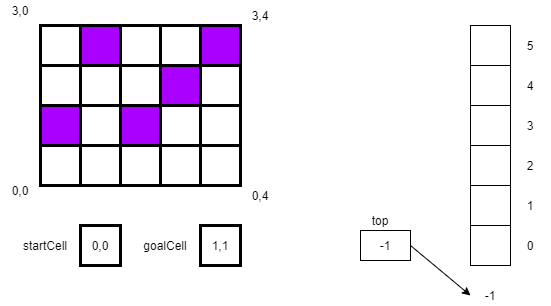

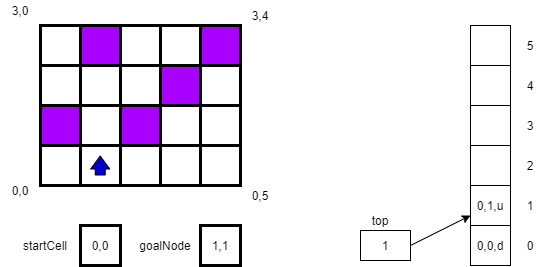

We start with a maze, a startCell, a goalCell, and a stack as shown below. In this case our startCell is 0,0 and our end goal is 1,1. We will store each location on the stack as we move to that location. We will also keep track of the direction we are headed: up, right, down, or left, which we’ll abbreviate as u,r,d,and l.

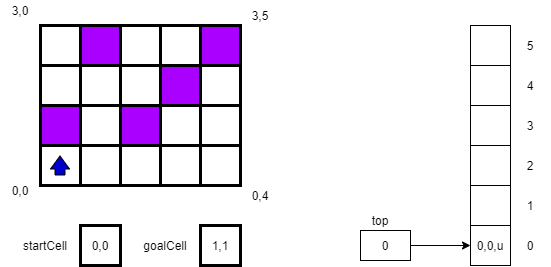

In our first step, we will store our location and direction 0,0,u on the stack.

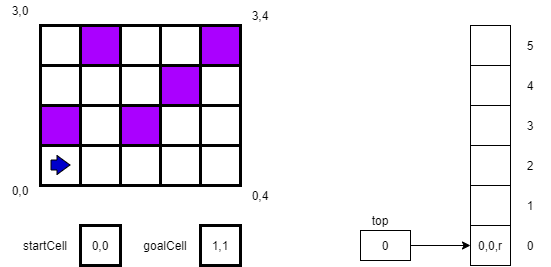

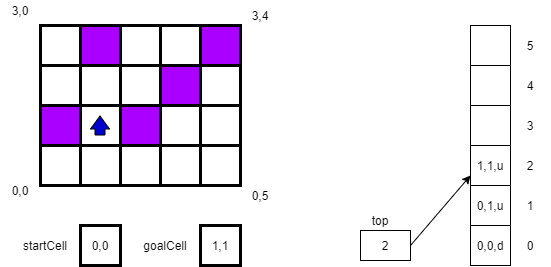

For the second step, we will try to move “up”, or to location 1,0. However, that square in the maze is blocked. So, we change our direction to r as shown below.

After turning right, we attempt to move in that direction to square 0,1, which is successful. Thus, we create a new location 0,1,u and push it on the stack. (Here we always assume we point up when we enter a new square.) The new state of the maze and our stack are shown below.

Next, we try to move to 1,1, which again is successful. We again push our new location 1,1,u onto the stack. And, since our current location matches our goalCell location (ignoring the direction indicator) we recognize that we have reached our goal.

Of course, it’s one thing to find our goal cell, but it’s another thing to get back to our starting position. However, we already know the path back given our wise choice of data structures. Since we stored the path in a stack, we can now simply reverse our path and move back to the start cell. All we need to do is pop the top location off of the stack and move to that location over and over again until the stack is empty. The pseudocode for following the path back home is simple.

loop while !MYSTACK.ISEMPTY()

NEXTLOCATION = MYSTACK.POP()

MOVETO(NEXTLOCATION)

end while