We’ve examined many different versions of a linear search algorithm. We can find the first occurrence of a number in an array, the last occurrence of that number, or a value with a particular property, such as the minimum value. Each of these are examples of a linear search, since we look at each element in the container sequentially until we find what we are looking for.

So, what would be the time complexity of this process? To understand that, we must consider what the worst-case input would be. For this discussion, we’ll just look at the find function, but the results are similar for many other forms of linear search. The pseudocode for find is included below for reference.

1function FIND(NUMBER, ARRAY)

2 loop INDEX from 0 to size of ARRAY - 1

3 if ARRAY[INDEX] == NUMBER

4 return INDEX

5 end if

6 end for

7 return -1

8end functionHow would we determine what the worst-case input for this function would be? In this case, we want to come up with the input that would require the most steps to find the answer, regardless of the size of the container. Obviously, it would take more steps to find a value in a larger container, but that doesn’t really tell us what the worst-case input would be.

Therefore, the time complexity for a linear search algorithm is clearly proportional to the number of items that we need to search through, in this case the size of our array. Whether we use an iterative algorithm or a recursive algorithm, we still need to search the array one item at a time. We’ll refer to the size of the array as $N$.

Here’s the key: when searching for minimum or maximum values, the search will always take exactly $N$ comparisons since we have to check each value. However, if we are searching for a specific value, the actual number of comparisons required may be fewer than $N$.

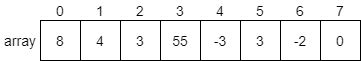

To build a worst-case input for the find function, we would search for the situation where the value to find is either the last value in the array, or it is not present at all. For example, consider the array we’ve been using to explore each linear search algorithm so far.

What if we are trying to find the value 55 in this array? In that case, we’ll end up looking at 4 of the 8 elements in the array. This would take $N/2$ steps. Can we think of another input that would be worse?

Consider the case where we try to find 0 instead. Will that be worse? In that case, we’ll need to look at all 8 elements in the array before we find it. That requires $N$ steps!

What if we are asked to find 1 in the array? Since 1 is not in the array, we’ll have to look at every single element before we know that it can’t be found. Once again, that requires $N$ steps.

We could say that in the worst-case, a linear search algorithm requires “on the order of $N$” time to find an answer. Put another way, if we double the size of the array, we would also need to double the expected number of steps required to find an item in the worst case. We sometimes call this linear time, since the number of steps required grows at the same rate as the size of the input.

Can We Do Better?

Our question now becomes, “Is a search that takes on the order of $N$ time really all that bad?”. Actually, it depends. Obviously, if $N$ is a small number (less than 1000 or so) it may not be a big deal, if you only do a single search. However, what if we need to do many searches? Is there something we can do to make the process of searching for elements even easier?

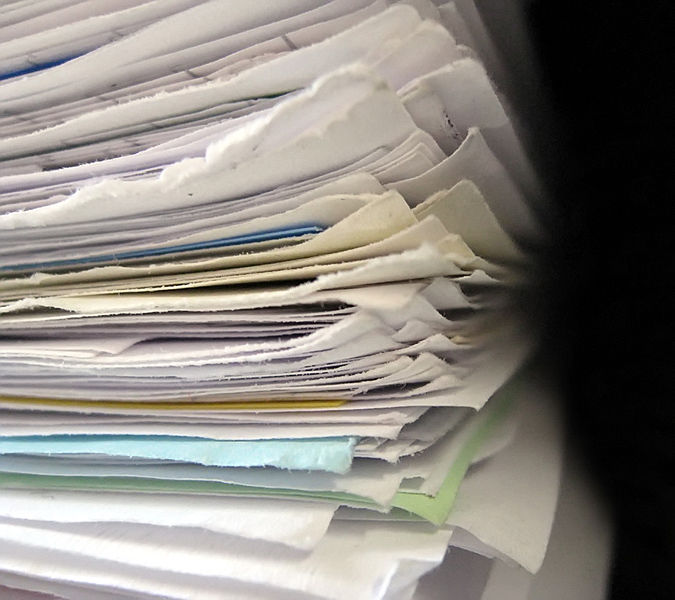

Let’s consider the real world once again for some insights. For example, think of a pile of loose papers on the floor. If we wanted to find a specific paper, how would we do it?

In most cases, we would simply have to perform a linear search, picking up each paper one at a time and seeing if it is the one we need. This is pretty inefficient, especially if the pile of papers is large.

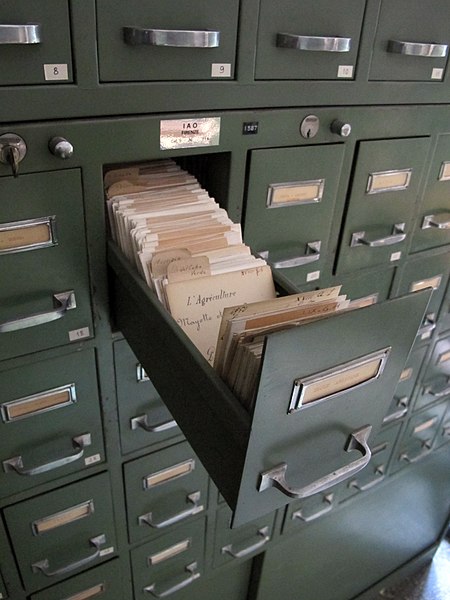

What if we stored the papers in a filing cabinet and organized them somehow? For example, could we sort the papers by title in alphabetical order? Then, when we want to find a particular paper, we can just skip to the section that contains files with the desired first letter and go from there. In fact, we could even do this for the second and third letter, continuing to jump forward in the filing cabinet until we found the paper we need.

This seems like a much more efficient way to go about searching for things. In fact, we do this naturally without even realizing it. Most computers have a way to sort files alphabetically when viewing the file system, and anyone who has a collection of items has probably spent time organizing and alphabetizing the collection to make it easier to find specific items.

Therefore, if we can come up with a way to organize the elements in our array, we may be able to make the process of finding a particular item much more efficient. In the next section, we’ll look at how we can use various sorting algorithms to do just that.

-

File:FileStack retouched.jpg. (2019, January 17). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 22:12, March 23, 2020 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:FileStack_retouched.jpg&oldid=335159723. ↩︎

-

File:Istituto agronomico per l’oltremare, int., biblioteca, schedario 05.JPG. (2016, May 1). Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Retrieved 22:11, March 23, 2020 from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Istituto_agronomico_per_l%27oltremare,_int.,_biblioteca,_schedario_05.JPG&oldid=194959053. ↩︎