Trees

All about trees!

All about trees!

For the next data structure in the course, we will cover trees, which are used to show hierarchical data. Trees can have many shapes and sizes and there is a wide variety of data that can be organized using them. Real world data that is appropriate for trees can include: family trees, management structures, file systems, biological classifications, anatomical structures and much more.

We can look at an example of a tree and the relationships they can show. Consider this file tree; it has folders and files in folders.

If we wanted to access the file elm.txt, we would have to follow this file path: Foo/B/Q/E/elm.txt. We can similarly store the file structure as a tree like we below. As before, if we wanted to get to the file elm.txt we would navigate the tree in the order: Foo -> B -> Q -> E -> elm.txt. As mentioned before, trees can be used on very diverse data sets; they are not limited to file trees!

In the last module we talked about strings which are a linear data structure. To be explicit, this means that the elements in a string form a line of characters. A tree, by contrast, is a hierarchal structure which is utilized best in multidimensional data. Going back to our file tree example, folders are not limited to just one file, there can be multiple files contained in a single folder- thus making it multidimensional.

Consider the string “abc123”; this is a linear piece of data where there is exactly one character after another. We can use trees to show linear data as well.

While trees can be used for linear data, it would be excessive and inefficient to implement them for single strings. In an upcoming module, we will see how we can use trees to represent any number of strings! For example, this tree below contains 7 words: ‘a’, ‘an’, ‘and’, ‘ant’, ‘any’, ‘all’, and ‘alp’.

In the next sections, we will discuss the properties of a tree data structure and how we would design one ourselves. Once we have a good understanding of trees and the properties of trees, we will implement our own.

The video incorrectly states the degree of a tree is equal to the degree of the root. The correct definition is that the degree of a tree is the largest degree of any node in the tree.

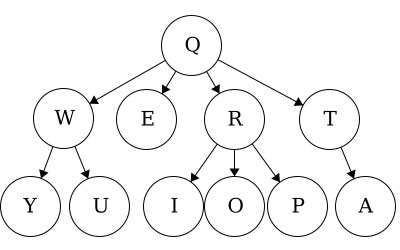

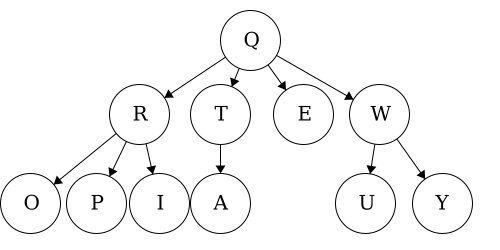

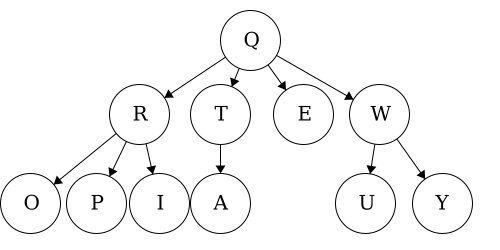

To get ourselves comfortable in working with trees, we will outline some standard vocabulary. Throughout this section, we will use the following tree as a guiding example for visualizing the definitions.

Node - the general term for a structure which contains an item, such as a character or even another data structure.Edge - the connection between two nodes. In a tree, the edge will be pointing in a downward direction.This tree has five edges and six nodes. There is no limit to the number of nodes in a tree. The only stipulation is that the tree is fully connected. This means that there cannot be disjoint portions of the tree. We will look at examples in the next section.

A rule of thumb for discerning trees is this: if you imagine holding the tree up by the root and gravity took effect, then all edges must be pointing downward. If an edge is pointing upward, we will have a cycle within our structure so it will not be a tree.

Root - the topmost node of the treeTo be a tree, there must be exactly one root. Having multiple roots, will result in a cycle or a tree that is not fully connected. In short, a cycle is a loop in the tree.

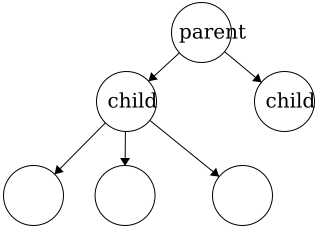

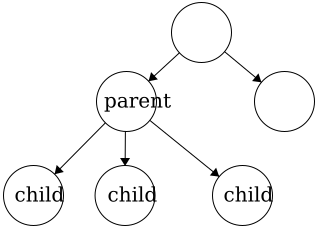

Parent - a node with an edge that connects to another node further from the root. We can also define the root of a tree with respect to this definition; Root: a node with no parent.Child - a node with an edge that connects to another node closer to the root.

In a tree, child nodes must have exactly one parent node. If a child node has more than one parent, then a

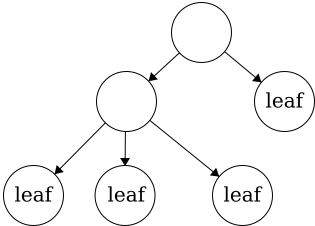

In a tree, child nodes must have exactly one parent node. If a child node has more than one parent, then a cycle will occur. If there is a node without a parent node, then this is necessarily the root node. There is no limit to the number of child nodes a parent node can have, but to be a parent node, the node must have at least one child node.Leaf - a node with no children.

This tree has four leaves. There is no limit to how many leaves can be in a tree.

This tree has four leaves. There is no limit to how many leaves can be in a tree.Degree

The degree of the nodes are shown as the values on the nodes in this example. The degree of the tree is the largest degree of any node in the tree. Thus, the degree for this tree is 3.

tree is defined recursively. This means that each child of the root is the root of another tree and the children of those are roots to trees as well. Again, this is a recursive definition so it will continue to the leaves. The leaves are also trees with just a single node as the root.

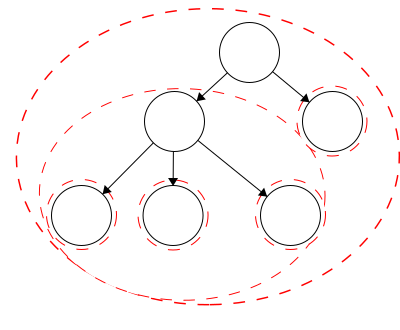

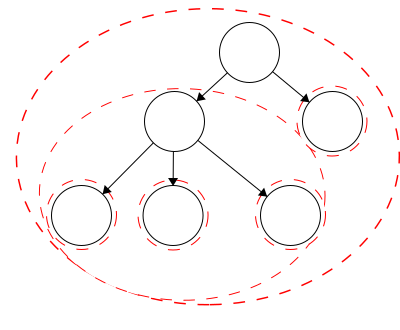

In our example tree, we have six trees. Each tree is outlined in a red dashed circle:

In our example tree, we have six trees. Each tree is outlined in a red dashed circle:

Trees can come in many shapes and sizes. There are, however some constraints to making a valid tree.

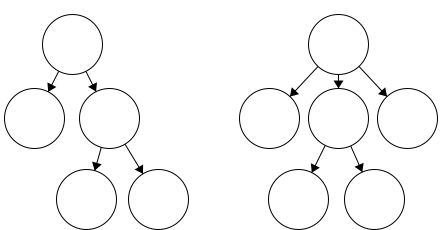

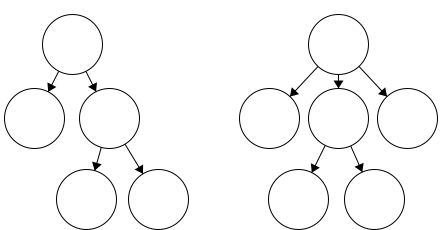

Any combination of the following represents a valid tree:

Below are some examples of invalid trees.

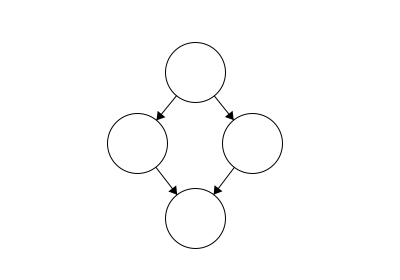

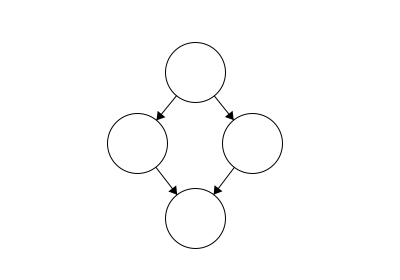

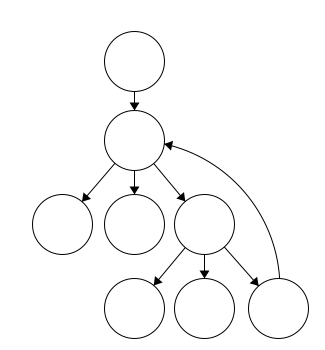

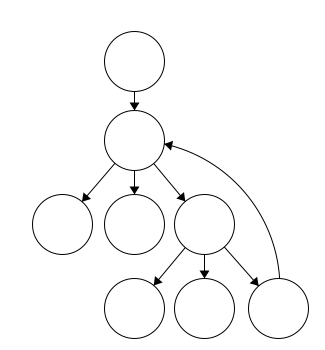

A cycle

Again, cycles are essentially loops that occur in our tree. In this example, we see that our leaf has two parents. One way to determine whether your data structure has a cycle is if there is more than one way to get from the root to any node.

Again, cycles are essentially loops that occur in our tree. In this example, we see that our leaf has two parents. One way to determine whether your data structure has a cycle is if there is more than one way to get from the root to any node.

A cycle

Here we can see another cycle. In this case, the node immediately after the root has two parents, which is a clue that a cycle exists. Another test

Here we can see another cycle. In this case, the node immediately after the root has two parents, which is a clue that a cycle exists. Another test

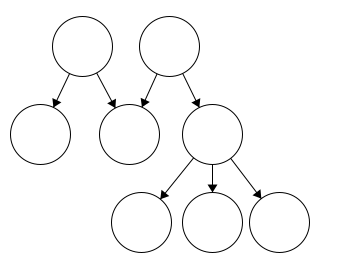

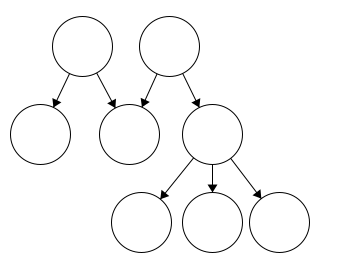

Two Roots

Trees must have a single root. In this instance, it may look like we have a tree with two roots. Working through this, we also see that the node in the center has two parents.

Trees must have a single root. In this instance, it may look like we have a tree with two roots. Working through this, we also see that the node in the center has two parents.

Two Trees

This example would be considered two trees, not a tree with two parts. In this figure, we have two fully connected components. Since they are not connected to each other, this is not a single tree.

This example would be considered two trees, not a tree with two parts. In this figure, we have two fully connected components. Since they are not connected to each other, this is not a single tree.

Along with understanding how trees work, we want to also be able to implement a tree of our own. We will now outline key components of a tree class.

Recall that trees are defined recursively so we can build them from the leaves up where each leaf is a tree itself. Each tree will have three properties: the item it contains as an object, its parent node of type MyTree, and its children as a list of MyTrees. Upon instantiation of a new MyTree, we will set the item value and initialize the parent node to None and the children to an empty list of type MyTree.

Suppose that we wanted to construct the following tree.

We would start by initializing each node as a tree with no parent, no children, and the item in this instance would be the characters. Then we build it up level by level by add the appropriate children to the respective parent.

Disclaimer: This implementation will not prevent all cycles. In the next module, we will introduce steps to prevent cycles and maintain true tree structures.

In this method, we will take a value as input and then check if that value is the item of a child of the current node. If the value is not the item for any of the node’s children then we should return none.

function FINDCHILD(VALUE)

FOR CHILD in CHILDREN

IF CHILD's ITEM is VALUE

return CHILD

return NONE

end functionEach of these will be rather straight forward; children, item, and parent are all attributes of our node, so we can have a getter function that returns the respective values. The slightly more involved task will be getting the degree. Recall that the degree of a node is equal to the number of children. Thus, we can simply count the number of children and return this number for the degree.

We will have two functions to check the node type: one to determine if the node is a leaf and one to determine if it is a root. The definition of a leaf is a node that has no children. Thus, to check if a node is a leaf, we can simply check if the number of children is equal to zero. Similarly, since the definition of a root is a node with no parent, we can check that the parent attribute of the node is None.

When we wish to add a child, we must fisrt make sure we are able to add the child.

MyTreeWe will return true if the child was successfully added and false otherwise while raising the appropriate errors.

function ADDCHILD(CHILD)

IF CHILD has PARENT

throw exception

IF CHILD is CHILD of PARENT

return FALSE

ELSE

append CHILD to PARENT's children

set CHILD's parent to PARENT

return TRUE

end functionAs an example, lets walk through the process of building the tree above:

a with item ‘A’b with item ‘B’c with item ‘C’d with item ‘D’e with item ‘E’f with item ‘F’g with item ‘G’h with item ‘H’i with item ‘I’g to tree dh to tree di to tree de to tree bf to tree bOnce we have completed that, visually, we would have the tree above and in code we would have:

a with parent_node = None, item = ‘A’, children = {b,c,d}b with parent_node = a, item = ‘B’, children = {e,f}c with parent_node = a, item = ‘C’, children = { }d with parent_node = a, item = ‘D’, children = {g,h,i}e with parent_node = b, item = ‘E’, children = { }f with parent_node = b, item = ‘F’, children = { }g with parent_node = d, item = ‘G’, children = { }h with parent_node = d, item = ‘H’, children = { }i with parent_node = d, item = ‘I’, children = { }Note: When adding a child we must currently be at the node we want to be the parent. Much like when you want to add a file to a folder, you must specify exactly where you want it. If you don’t, this could result in a wayward child.

In the case of removing a child, we first need to check that the child we are attempting to remove is an instance of MyTree. We will return true if we successfully remove the child and false otherwise.

function REMOVECHILD(CHILD)

IF CHILD in PARENT'S children

REMOVE CHILD from PARENT's children

SET CHILD's PARENT to NONE

return TRUE

ELSE

return FALSE

end functionAs with adding a child, we need to ensure that we are in the ‘right place’ when attempting to remove a child. When removing a child, we are not ’erasing’ it, we are just cutting the tie from parent to child and child to parent. Consider removing d from a. Visually, we would have two disjoint trees, shown below:

In code, we would have:

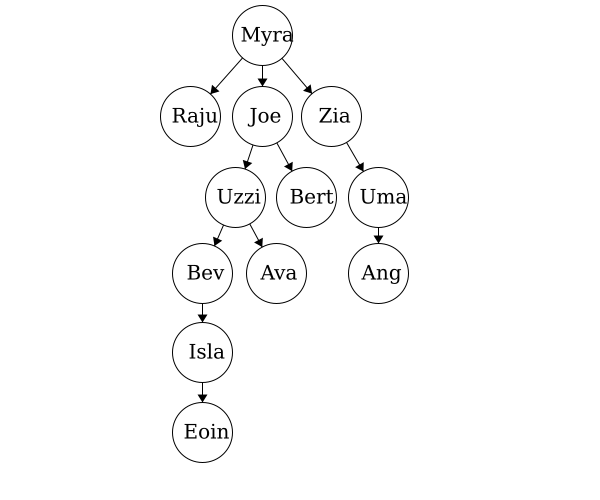

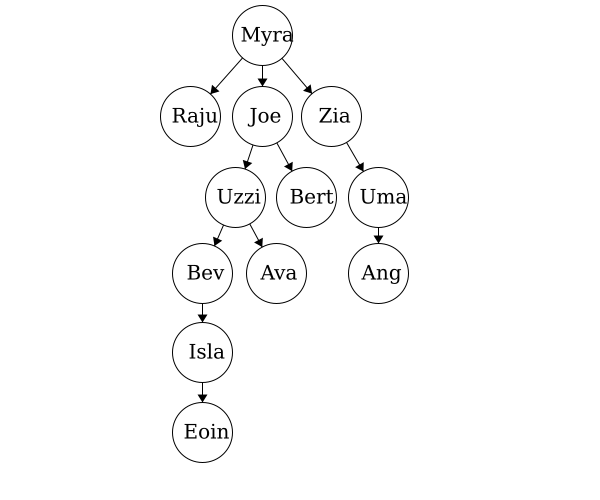

a with parent_node = None, item = ‘A’, children = {b,c}b with parent_node = a, item = ‘B’, children = {e,f}c with parent_node = a, item = ‘C’, children = { }d with parent_node = None, item = ‘D’, children = {g,h,i}e with parent_node = b, item = ‘E’, children = { }f with parent_node = b, item = ‘F’, children = { }g with parent_node = d, item = ‘G’, children = { }h with parent_node = d, item = ‘H’, children = { }i with parent_node = d, item = ‘I’, children = { }Many of the terms used in trees relate to terms used in family trees. Having this in mind can help us to better understand some of the terminology involved with abstract trees. Here we have a sample family tree.

Ancestor - The ancestors of a node are those reached from child to parent relationships. We can think of this as our parents and our parent’s parents, and so on.

Descendant - The descendants of a node are those reached from parent to child relationships. We can think of this as our children and our children’s children and so on.

Siblings - Nodes which share the same parent

We can describe the sizes of trees and position of nodes using different terminology, like level, depth, and height.

Level - The level of a node characterizes the distance between the node and the root. The root of the tree is considered level 1. As you move away from the tree, the level increases by one.

Depth - The depth of a node is its distance to the root. Thus, the root has depth zero. Level and depth are related in that: level = 1 + depth.

Height of a Node - The height of a node is the longest path to a leaf descendant. The height of a leaf is zero.

Height of a Tree - The height of a tree is equal to the height of the root.

When working with multidimensional data structures, we also need to consider how they would be stored in a linear manner. Remember, pieces of data in computers are linear sequences of binary digits. As a result, we need a standard way of storing trees as a linear structure.

Path - a path is a sequence of nodes and edges, which connect a node with its descendant. We can look at some paths in the tree above:

Q to O: QRO

Traversal is a general term we use to describe going through a tree. The following traversals are defined recursively.

Pre refers to the root, meaning the root goes before the children.QWYUERIOPTA

Post refers to the root, meaning the root goes after the children.YUWEIOPRATQ

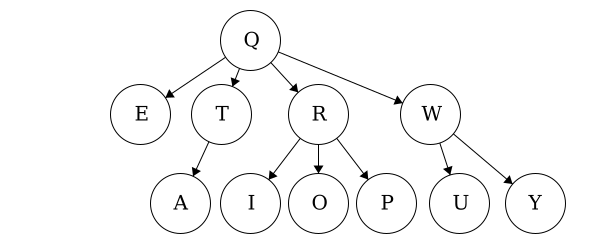

When we talk about traversals for general trees we have used the phrase ’the traversal could result in’. We would like to expand on why ‘could’ is used here. Each of these general trees are the same but their traversals could be different. The key concept in this is that for a general tree, the children are an unordered set of nodes; they do not have a defined or fixed order. The relationships that are fixed are the parent/child relationships.

| Tree | Preorder | Postorder |

|---|---|---|

| Tree 1 | QWYUERIOPTA |

YUWEIOPRATQ |

| Tree 2 | QETARIOPWUY |

EATIOPRUYWQ |

| Tree 3 | QROPITAEWUY |

OPIRATEUYWQ |

A binary tree is a type of tree with some special conditions. First, it must follow the guidelines of being a tree:

The special conditions that we impose on binary trees are the following:

To reinforce these concepts, we will look at examples of binary trees and examples that are not binary trees.

This is a valid binary tree. We have a single node, the root, with no children. As with general trees, binary trees are built recursively. Thus, each node and its child(ren) are trees themselves.

This is also a valid binary tree. All of the left children are less than their parent. The node with item ‘10’ is also in the correct position as it is less than 12, 13, and 14 but greater than 9.

We have the same nodes but our root is now 12 whereas before it was 14. This is also a valid binary tree.

Here we have an example of a binary tree with alphabetical items. As long as we have items which have a predefined order, we can organize them using a binary tree.

We may be inclined to say that this is a binary tree: each node has 0, 1, or 2 children and amongst children and parent nodes, the left child is smaller than the parent and the right child is greater than the parent. However, in binary trees, all of the nodes in the left tree must be smaller than the root and all of the nodes in the right tree must be larger than the root. In this tree, D is out of place. Node D is less than node T but it is also less than node Q. Thus, node D must be on the right of node Q.

In this case, we do not have a binary tree. This does fit all of the criteria for being a tree but not the criteria for a binary tree. Nodes in binary trees can have at most 2 children. Node 30 has three children.

In the first module we discussed two types of traversals: preorder and postorder. Within that discussion, we noted that for general trees, the preorder and postorder traversal may not be unique. This was due to the fact that children nodes are an unordered set.

We are now working with binary trees which have a defined child order. As a result, the preorder and postorder traversals will be unique! These means that for a binary tree when we do a preorder traversal there is exactly one string that is possible. The same applies for postorder traversals as well.

Recall that these were defined as such:

Now for binary trees, we can modify their definitions to be more explicit:

Let’s practice traversals on the following binary tree.

Since we have fixed order on the children, we can introduce another type of traversal: in-order traversal.

In-order Traversal:

While this is a valid binary tree, it is not balanced. Let’s look at the following tree.

We have the same nodes but our root is now 12 whereas before it was 14. This is a valid binary tree. We call this a balanced binary tree. A balanced binary tree looks visually even amongst the left and right trees in terms of number of nodes.

Note: Balancing is not necessary for a valid binary tree. It is, however, important in terms of time efficiency to have a balanced tree. For example, the number of actions when inserting an element is about the same as the number of levels in the tree. If we tried to add the value 11 into the unbalanced tree, we would traverse 5 nodes. If we tried to add the value 11 in to the balanced tree, we would traverse just 3 nodes.

We believe that balancing binary trees is out of the scope of this course. If you are interested in how we might balance a tree, feel free to check out these videos by Dr. Joshua Weese.

YouTube Video YouTube VideoIn this module we have introduce vocabulary related to trees and what makes a tree a tree. To recap, we have introduced the following:

Child - a node with an edge that connects to another node closer to the root.Degree

Degree of a node - the number of children a node has. The degree of a leaf is zero.Degree of a tree - the degree of an entire tree is the largest degree of any node found in the tree.Edge - connection between two nodes. In a tree, the edge will be pointing in a downward direction.Leaf - a node with no children.Node - the general term for a structure which contains an item, such as a character or even another data structure.Parent - a node with an edge that connects to another node further from the root. We can also define the root of a tree with respect to this definition;Root - the topmost node of the tree; a node with no parent.Now we will work on creating our own implementation of a tree. These definitions will serve as a resource to us when we need refreshing on meanings; feel free to refer back to them as needed.

We discussed more terminology related to trees as well as tree traversals. To recap the new vocabulary:

Ancestor - The ancestors of a node are those reached from child to parent relationships. We can think of this as our parents and the parents of our parents, and so on.Depth - The depth of a node is its distance to the root. Thus, the root has depth zero. Level and depth are related in that: level = 1 + depth.Descendant - The descendants of a node are those reached from parent to child relationships. We can think of this as our children and our children’s children and so on.Height of a Node - The height of a node is the longest path to a leaf descendant. The height of a leaf is zero.Height of a Tree - The height of a tree is equal to the height of the root.Level - The level of a node characterizes the distance the node is from the root. The root of the tree is considered level 1. As you move away from the tree, the level increases by one.Path - a sequence of nodes and edges which connect a node with its descendant.Siblings - Nodes which share the same parentTraversal is a general term we use to describe going through a tree. The following traversals are defined recursively.