Trees

There are three types of trees to consider: generic trees, tries, and binary trees.

General Trees

-

Insert: In general, inserting an element into a tree by making it a child of an existing tree is a constant time operation. However, this depends on us already having access to the parent tree we’d like to add the item to, which may require searching for that element in the tree as discussed below, which runs in linear time based on the size of the tree. As we saw in our projects, one way we can simplify this is using a hash table to help us keep track of the tree nodes while we build the tree, so that we can more quickly access a desired tree (in near constant time) and add a new child to that tree.

-

Access: Again, this is a bit complex, as it requires us to make some assumptions about what information is available to us. Typically, we can only access the root element of a tree, which can be done in constant time. If we’d like to access any of the other nodes in the tree, we’ll have to traverse the tree to find them, either by searching for them if we don’t know the path to the item (which is linear time based on the size of the tree), or directly walking the tree in the case that we do know the path (which is comparable to the length of the path, or linear based on the height of the tree).

-

Find: Finding a particular node in a generic tree is a linear time operation based on the number of nodes in the tree. We simply must do a full traversal of the tree until we find the element we are searching for, typically either by performing a preorder or postorder traversal. This is very similar to simply looking at each element in a linear data structure.

-

Delete: Removing a child from an existing tree is an interesting operation. If we’ve already located the tree node that is the parent of the element we’d like to remove, and we know which child we’d like to remove, then the operation would be a linear time operation related to the number of children of that node. This is because we may have to iterate through the children of that tree node in order to find the one we’d like to remove. Recall that trees generally store the children of each node in a linked list or an array, so the time it takes to remove a child is similar to the time it takes to remove an element from those structures. Again, if we have to search for either the parent or the tree node we’d like to remove from that parent, we’ll have to take that into account.

-

Memory: In terms of memory usage, a generic tree uses memory that is on the order of the number of nodes in the tree. So, as the number of nodes in the tree is doubled, the amount of memory it uses doubles as well.

Tries

Tries improve on the structure of trees in one important way - instead of using a generic list to store each child, they typically use a statically sized array, where each index in the array directly corresponds to one of the possible children that the node could have. In the case of a trie that represents words, each tree node may have an array of 26 possible children, one for each letter of the alphabet. In our implementation, we chose to use lists instead to simplify things a bit, but for this analysis we’ll assume that the children of a trie node can be accessed in constant time through the use of these static arrays.

In the analysis below, we’ll assume that we are dealing with words in a trie, not individual nodes. We’re also going to be always starting with the root node of the overall trie data structure.

-

Insert: To insert a new word in a trie, the process will run in linear time based on the length of the word. So, to insert a 10 character word in a trie, it should take on the order of 10 steps. This is because we can find each individual node for each character in constant time since we are using arrays as described above, and we’ll need to do that once for each character, so the overall time is linear based on the number of characters. If the path doesn’t exist, we’ll have to create new tree nodes to fill it in, but if the path does exist, it could be as simple as setting the boolean value at the correct node to indicate that it is indeed a word.

-

Access: Similarly to determine if a particular word is in the trie, it will also run in linear time based on the length of the word. We simply must traverse through the path in the tree, and at each node it is a constant time operation to find the correct child and continue onward. So, in total this is a linear time operation.

-

Find: Find is pretty much the same as access, since we can’t just directly jump to a particular node in the tree. So, this is also in linear time based on the length of the word.

-

Delete: Once again, deleting a word simply involves finding it, which runs in linear time. Once it is deleted, we may go through and prune branches that are unused, which is also a linear time operation as we work back upwards in the trie. So, overall the whole operation runs in linear time based on the length of the word.

In summary, pretty much every operation performed on a trie is related to the length of the word that is provided as input. Pretty nifty!

- Memory: Analyzing the memory usage of a trie is a bit more interesting. Traditionally, we say that the memory consumed by a trie is on the order of $n * m$, where $n$ is the number of words stored in the trie, and $m$ is the length of the longest word in the trie. We come to this value because there could be $n$ words that do not share any prefixes, and if they are all the same length $n$ then we’ll need that many nodes to represent the whole trie. However, in practice the actual memory usage may be somewhat less because of the shared prefixes and shorter words being part of longer words, but remember that we are concerned with the worst case memory usage for a trie, which is $n * m$.

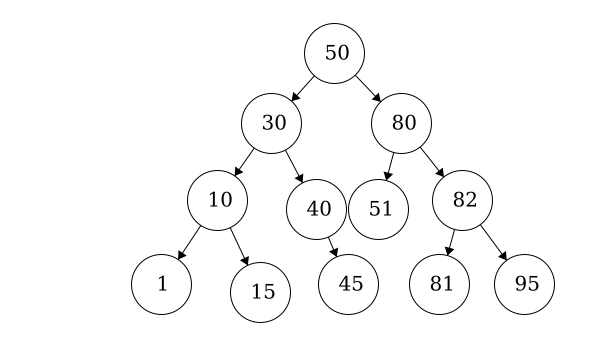

Binary Trees

A binary tree is a tree that is limited to having only two children of each node, and the children and parents are sorted such that every element to the left of the node is less than or equal to its value, and all elements to the right of the node are greater than or equal to its value. Because of this, they perform a little differently than traditional trees.

One major concept related to binary trees is whether the tree is “balanced” or not. A balanced tree has children that differ in height by no more than 1. If the tree is perfectly balanced, meaning all subtrees are balanced, then there are some interesting relationships that develop.

Most notably, the overall height $h$ of the tree is no larger than $log_2(n)$, where $n$ is the number of elements in the tree.

We didn’t cover the algorithms to balance a binary tree in this course since they can be a bit complex, but for this analysis we’ll discuss the performance of binary trees when they are perfectly balanced as well as when they are unbalanced.

-

Insert: To insert a new element in a binary tree, we may have to descend all the way to the bottom of the tree, so the operation is linear based on the height of the tree. If the tree is a perfectly balanced binary tree, then it is on the order of $log_2(n)$. Otherwise, it is linear based on the height, which in the worst case of a completely unbalanced tree could be the number of nodes itself. Once you’ve added the new item, a perfectly balance tree may need to rebalance itself, but that operation is not any more costly than the insert operation.

-

Access: Similarly, to access a particular element in a binary tree, we’ll have to descend through the tree until we find the element we are looking for. At each level, we know exactly which child to check, so it is once again related to the height of the tree. If the tree is a perfectly balanced binary tree, then it is on the order of $log_2(n)$. Otherwise, it is linear based on the height, which in the worst case of a completely unbalanced tree could be the number of nodes itself.

-

Find: Once again, find in this instance is similar to access.

-

Delete: Finally, deleting an element from a binary tree involves finding the element, which will be linear based on the height of the tree. Once the element is removed, then a perfectly balanced tree will need to rebalance itself, which could also take the same amount of time. So, in both cases, it runs on the order of $h$ time, which in the worst case is the total number of nodes $n$ on an unbalanced tree, or $log_2(n)$ on a perfectly balanced tree.

So, most operations involving a perfectly balanced binary tree run in $log_2(n)$ time, which is very efficient when compared to a generic tree. However, if the tree is not balanced, then we cannot make any assumptions about the height of the tree and each operation could require $n$ time, where $n$ is the number of nodes in the tree.

- Memory: The memory usage of a binary tree is directly correlated with the number of nodes, so we typically say that it is on the order of $n$ memory usage.