Need for Test Doubles

YouTube VideoAs we build larger and larger applications, we may find that it becomes more and more difficult to see the entire application as a whole. Instead, it helps to think of the application as many different modules, and each module interacts with others based on their publicly available methods, which make up the application programming interface or API of the module.

Ideally, we’d like each module of the program to be independent from the others, with each one having a clear purpose or reason for inclusion in the program. This is a key part of the design principle separation of concerns, which involves breaking larger systems down into distinct sections that address a particular “concern” within the larger system.

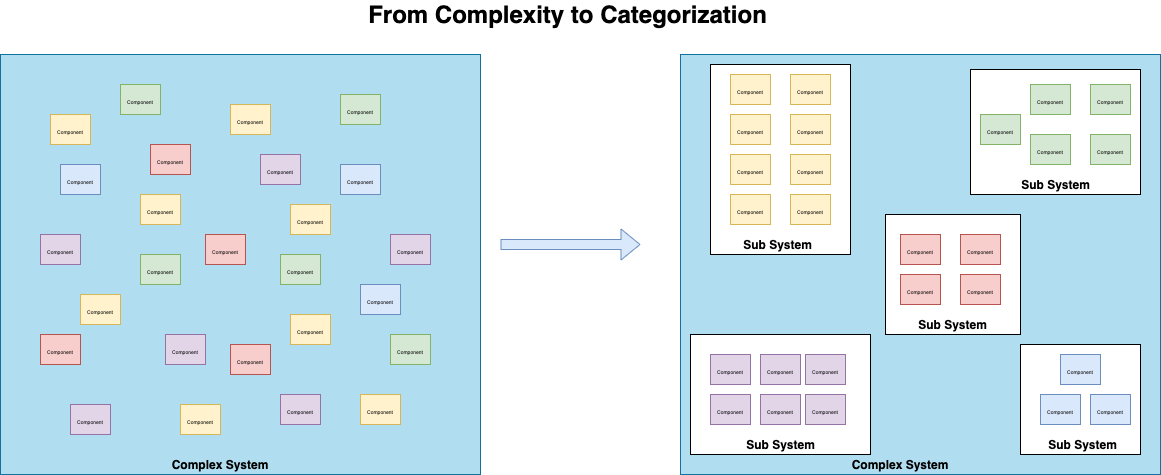

So, by categorizing the individual classes in our application based on similarity, we can then start to organize our application into modules of code that are somewhat independent of each other. They still interact through the public APIs of each module, but the internal workings of one module should not be visible to another.

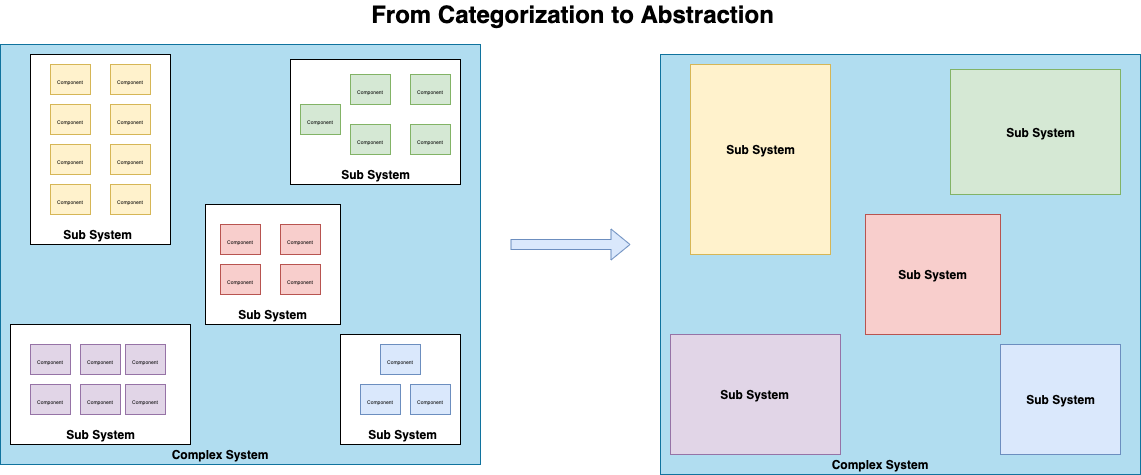

Once we start writing unit tests for our code, we can start to abstract away the details of other modules in the system, and focus just on the internal workings of the single unit of code, usually a class or method, that we intend to test.

However, this is difficult when our code has to call methods that are present in another module. How can we test our code and make sure it works, without also having to test that the module it is calling also works correctly and returns a correct value? If we cannot figure out a way to do this, then unit testing our code is not very helpful since it won’t allow us to accurately pinpoint the location of an error.

Test Doubles

This is where the concept of test doubles comes in. Let’s say our code needs to call a method called getArea() that is part of the API of another module, which will calculate the area of a given shape. All our code needs to do is compare the returned value of that method with a few key values, and display a result.

Depending on the shape, calculating the area can be a computationally intensive process, so we probably don’t want to do that many times in our unit tests. In addition, since that method is contained in another module, we definitely don’t want to test that it actually returns the correct answer.

Instead, we just know that the API of that module says that the getArea() method will return a floating-point value that is non-negative. This is a postcondition that is well documented in the API, so as long as that module is working correctly, we know that the getArea() method will return some non-negative floating-point value.

Therefore, instead of calling the getArea() method that is contained in the external module, we can create a stub method that simply returns a non-negative floating-point value. Then, whenever our code calls getArea(), we can intercept that message and direct it instead to our stub method, which quickly returns a valid value that we can use in our tests. We can even modify the stub to return either the exact values we want, or just any random value.

There are many more powerful things we can do with these test doubles, such as:

- Verify that a particular method is called within our code based on an input condition

- Produce some fake data that our code can operate on that is not provided via arguments (an “indirect input”)

- Verify that our code updates data in another module properly (an “indirect output”)

- Observe how many times our code instantiates a particular type of object.

Test doubles are a crucial part of writing more useful and advanced unit tests, especially as our programs become larger and we wish to test portions of the code that are integrated with other modules.

References

- Test Double at xUnit Patterns

- Test Doubles - Fakes, Mocks and Stubs at Pragmatists blog