The Growth of Computing

By this point, you should be familiar enough with the history of computers to be aware of the evolution from the massive room-filling vacuum tube implementations of ENIAC, UNIVAC, and other first-generation computers to transistor-based mainframes like the PDP-1, and the eventual introduction of the microcomputer (desktop computers that are the basis of the modern PC) in the late 1970’s. Along with a declining size, each generation of these machines also cost less:

| Machine | Release Year | Cost at Release | Adjusted for Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENIAC | 1945 | $400,000 | $5,288,143 |

| UNIVAC | 1951 | $159,000 | $1,576,527 |

| PDP-1 | 1963 | $120,000 | $1,010,968 |

| Commodore PET | 1977 | $795 | $5,282 |

| Apple II (4K RAM model) | 1977 | $1,298 | $8,624 |

| IBM PC | 1981 | $1,565 | $4,438 |

| Commodore 64 | 1982 | $595 | $1,589 |

This increase in affordability was also coupled with an increase in computational power. Consider the ENIAC, which computed at 100,000 cycles per second. In contrast, the relatively inexpensive Commodore 64 ran at 1,000,000 cycles per second, while the more pricy IBM PC ran at 4,770,000 cycles per second.

Not surprisingly, governments, corporations, schools, and even individuals purchased computers in larger and larger quantities, and the demand for software to run on these platforms and meet these customers’ needs likewise grew. Moreover, the sophistication expected from this software also grew. Edsger Dijkstra described it in these terms:

The major cause of the software crisis is that the machines have become several orders of magnitude more powerful! To put it quite bluntly: as long as there were no machines, programming was no problem at all; when we had a few weak computers, programming became a mild problem, and now we have gigantic computers, programming has become an equally gigantic problem.Edsger Dijkstra, The Humble Programmer (EWD340), Communications of the ACM

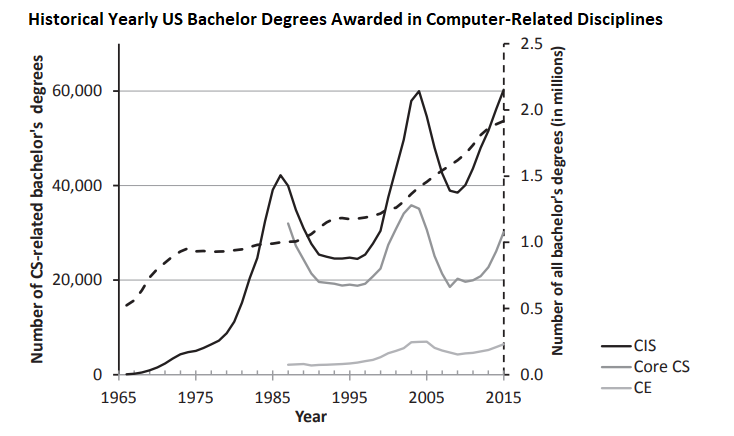

Coupled with this rising demand for programs was a demand for skilled software developers, as reflected in the following table of graduation rates in programming-centric degrees (the dashed line represents the growth of all bachelor degrees, not just computer-related ones):

Unfortunately, this graduation rate often lagged far behind the demand for skilled graduates, and was marked by several periods of intense growth (the period from 1965 to 1985, 1995-2003, and the current surge beginning around 2010). During these surges, it was not uncommon to see students hired directly into the industry after only a course or two of learning programming (coding boot camps are a modern equivalent of this trend).

All of these trends contributed to what we now call the Software Crisis.