Programs in Memory

Info

The above video and below textbook content cover the same ideas (but are not identical). Feel free to pick one or the other.

Before we move on to our next concept, it is helpful to explore how programs use memory. Remember that modern computers are stored program computers, which means the program as well as the data are stored in the computer’s memory. A Universal Turing Machine, the standard example of a stored program computer, reads the program from the same paper tape that it reads its inputs to and writes its output to. In contrast, to load a program in the ENIAC, the first electronic computer in the United States, programmers had to physically rewire the computer (it was later modified to be a stored-program computer).

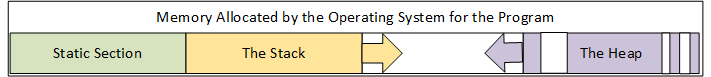

When a program is run, the operating system allocates part of the computer’s memory (RAM) for the program to use. This memory is divided into three parts - the static memory, the stack, and the heap.

The program code itself is copied into the static section of that memory, along with any literals (1, "Foo"). Additionally, the space to hold any variables that are declared static is allocated here. The reason this memory space is called static is that it is allocated when the program begins, and remains allocated for as long as the program is running. It does not grow or shrink (though the value of static variables may change).

The stack is where the space for scoped variables is allocated. We often call it the stack because functionally it is used like the stack data structure. The space for global variables is allocated first, at the “bottom” of the stack. Then, every time the program enters a new scope (i.e. a new function, a new loop body, etc.) the variables declared there are allocated on the stack. When the program exits that scope (i.e. the function returns, the loop ends), the memory that had been reserved for those values is released (like the stack pop operation).

Thus, the stack grows and shrinks over the life of the program. The base of the stack is against the static memory section, and it grows towards the heap. If it grows too much, it runs out of space. This is the root cause of the nefarious stack overflow exception. The stack has run out of memory, most often because an infinite recursion or infinite loop.

Finally, the heap is where dynamically allocated memory comes from - memory the programmer specifically reserved for a purpose. In C programming, you use the calloc(), malloc(), or realloc() to allocate space manually. In Object-Oriented languages, the data for individual objects are stored here. Calling a constructor with the new keyword allocates memory on the heap, the constructor then initializes that memory, and then the address of that memory is returned. We’ll explore this process in more depth shortly.

This is also where the difference between a value type and a reference type comes into play. Value types include numeric objects like integers, floating point numbers, and also booleans. Reference types include strings and classes. When you create a variable that represents a value type, the memory to hold its value is created in the stack. When you create a variable to hold a reference type, it also has memory in the stack - but this memory holds a pointer to where the object’s actual data is allocated in the heap. Hence the term reference type, as the variable doesn’t hold the object’s data directly - instead it holds a reference to where that object exists in the heap!

This is also where null comes from - a value of null means that a reference variable is not pointing at anything.

The objects in the heap are not limited to a scope like the variables stored in the stack. Some may exist for the entire running time of the program. Others may be released almost immediately. Accordingly, as this memory is released, it leaves “holes” that can be re-used for other objects (provided they fit). Many modern programming languages use a garbage collector to monitor how fragmented the heap is becoming, and will occasionally reorganize the data in the heap to make more contiguous space available.