WPF Features

Windows Presentation Foundation is a library and toolkit for creating Graphical User Interfaces - a user interface that is presented as a combination of interactive graphical and text elements commonly including buttons, menus, and various flavors of editors and inputs. GUIs represent a major step forward in usability from earlier programs that were interacted with by typing commands into a text-based terminal (the EPIC software we looked at in the beginning of this textbook is an example of this earlier form of user interface).

You might be wondering why Microsoft introduced WPF when it already had support for creating GUIs in its earlier Windows Forms product. In part, this decision was driven by the evolution of computing technology.

Screen Resolution and Aspect Ratio

No doubt you are used to having a wide variety of screen resolutions available across a plethora of devices. But this was not always the case. Computer monitors once came in very specific, standardized resolutions, and only gradually were these replaced by newer, higher-resolution monitors. The table below summarizes this time, indicating the approximate period each resolution dominated the market.

| Standard | Size | Peak Years |

|---|---|---|

| VGA | 640x480 | 1987-1990 |

| SVGA | 800x600 | 1990-2003 |

| XGA | 1024x768 | 2007-2015 |

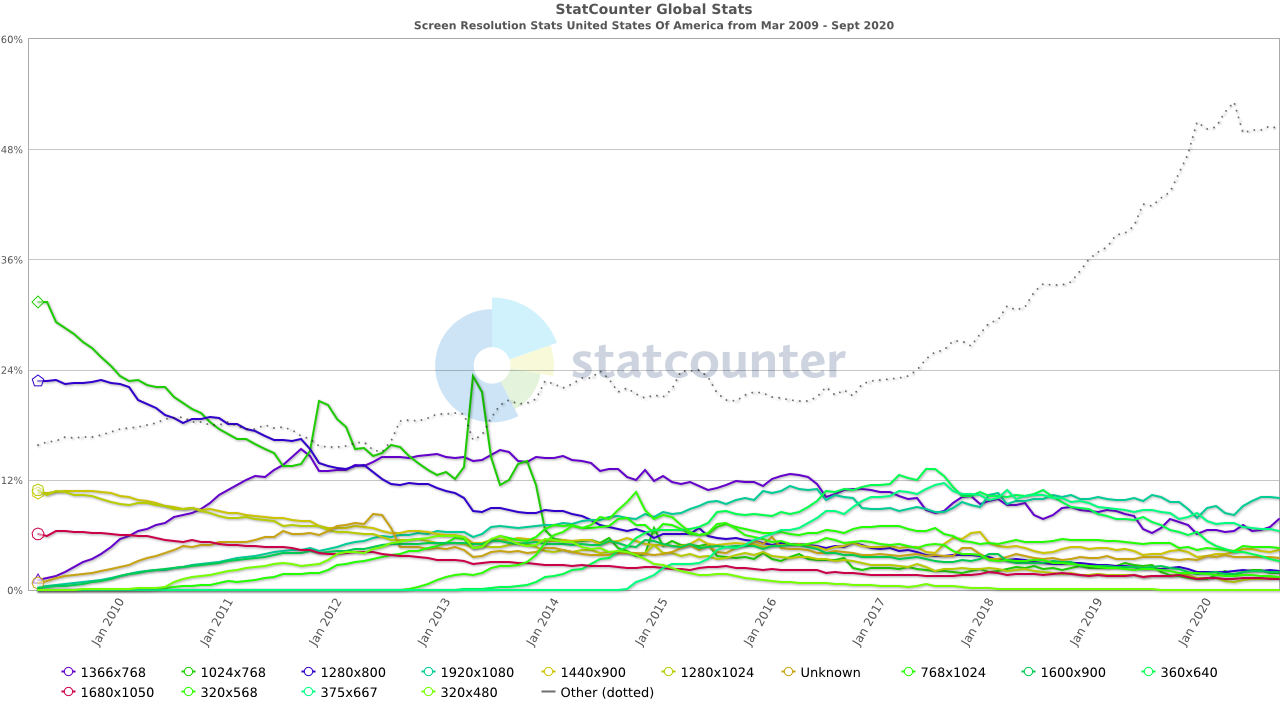

Windows Forms was introduced in the early 2000’s, at a time where the most popular screen resolution in the United States was transitioning from SVGA to XGA, and screen resolutions (especially for business computers running Windows) had remained remarkably consistent for long periods. Moreover, these resolutions were all using the 4:3 aspect ratio (the ratio of width to height of the screen). Hence, the developers of Windows forms did not consider the need to support vastly different screen resolutions and aspect ratios. Contrast that with trends since that time:

There is no longer a clearly dominating resolution, nor even an aspect ratio! Thus, it has become increasingly important for Windows applications to adapt to different screen resolutions. Windows Forms does not do this easily - each element in a Windows Forms application has a statically defined width and height, as well as its position in the window. Altering these values in response to different screen resolution requires significant calculations to resize and reposition the elements, and the code to perform these calculations must be written by the programmer.

In contrast, WPF adopts a multi-pass layout mechanism similar to that of a web browser, where it calculates the necessary space for each element within the GUI, then adapts the layout based on the actual space. With careful design, the need for writing code to position and size elements is eliminated, and the resulting GUIs adapt well to the wide range of available screen sizes.

Direct3D and Hardware Graphics Acceleration

Another major technology shift was the widespread adoption of hardware-accelerated 3D graphics. In the 1990’s this technology was limited to computers built specifically for playing video games, 3D modeling, video composition, or other graphics-intensive tasks. But by 2006, this hardware had become so widely accepted that with Windows Vista, Microsoft redesigned the Windows kernel to leverage this technology to take on the task of rendering windows applications.

WPF leveraged this decision and offloads much of the rendering work to the graphics hardware. This meant that WPF controls could be vector-based, instead of the raster-based approach adopted by Windows Forms. Vector-based rendering means the image to be drawn on-screen is created from instructions as needed, rather than copied from a bitmap. This allows controls to look as sharp when scaled to different screen resolutions or enhanced by software intended to support low-vision users. Raster graphics scaled the same way will look pixelated and jagged.

Leveraging the power of hardware accelerated graphics also allowed for the use of more powerful animations and transitions, as well as freeing up the CPU for other tasks. It also simplifies the use of 3D graphics in windows applications. WPF also leveraged this power to provide a rich storyboarding and animation system as well as inbuilt support for multimedia. In contrast, Windows Forms applications are completely rendered using the CPU and offer only limited support for animations and multimedia resources.

Customizable Styling and Template System

One additional shift is that Windows forms leverage controls built around graphical representations provided directly by the hosting Windows operating system. This helped keep windows applications looking and feeling like the operating system they were deployed on, but limits the customizability of the controls. A commonly attempted feature - placing an image on a button - becomes an onerous task within Windows Forms. Attempting to customize controls often required the programmer to take over the rendering work entirely, providing the commands to render the raw shapes of the control directly onto the control’s canvas. Unsurprisingly, an entire secondary market for pre-developed custom controls emerged to help counter this issue.

In contrast, WPF separated control rendering from windows subsystems, and implemented a declarative style of defining user interfaces using Extensible Application Markup Language (XAML). This provides the programmer complete control over how controls are rendered, and multiple mechanisms of increasing complexity to accomplish this. Style properties can be set on individual controls, or bundled into “stylesheets” and applied en-masse. Further, each control’s default style is determined by a template that can be replaced with a custom implementation, completely altering the appearance of a control.

This is just the tip of the iceberg - WPF also features a new and robust approach to data binding that will be subject of its own chapter, and allows for UI to be completely separated from logic, allowing for more thorough unit testing of application code.