Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol

At the heart of the world wide web is the Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP). This is a protocol defining how HTTP servers (which host web pages) interact with HTTP clients (which display web pages).

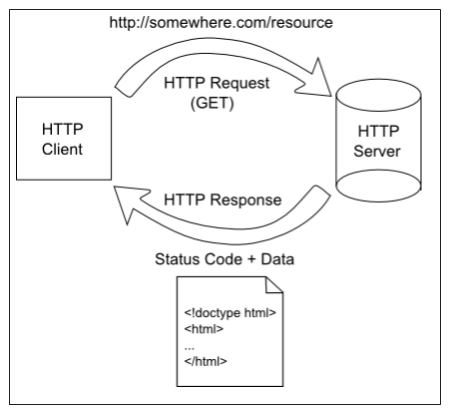

It starts with a request initiated from the web browser (the client). This request is sent over the Internet using the TCP protocol to a web server. Once the web server receives the request, it must decide the appropriate response - ideally sending the requested resource back to the browser to be displayed. The following diagram displays this typical request-response pattern.

This HTTP request-response pattern is at the core of how all web applications communicate. Even those that use websockets begin with an HTTP request.

The HTTP Request

A HTTP Request is just text that follows a specific format and sent from a client to a server. It consists of one or more lines terminated by a CRLF (a carriage return and a line feed character, typically written \r\n in most programming languages).

- A request-line describing the request

- Additional optional lines containing HTTP headers. These specify details of the request or describe the body of the request

- A blank line, which indicates the end of the request headers

- An optional body, containing any data belonging of the request, like a file upload or form submission. The exact nature of the body is described by the headers.

The HTTP Response

Similar to an HTTP Request, an HTTP response consists of one or more lines of text, terminated by a CRLF (sequential carriage return and line feed characters):

- A status-line indicating the HTTP protocol, the status code, and a textual status

- Optional lines containing the Response Headers. These specify the details of the response or describe the response body

- A blank line, indicating the end of the response metadata

- An optional response body. This will typically be the text of an HTML file, or binary data for an image or other file type, or a block of bytes for streaming data.

Making a Request

With our new understanding of HTTP requests and responses as consisting of streams of text that match a well-defined format, we can try manually making our own requests, using a Linux command line tool netcat.

Open a PowerShell instance (Windows) or a terminal (Mac/Linux) and enter the command:

$ ssh [eid]@cslinux.cs.ksu.edu

Alternatively, you can use Putty to connect to cslinux. Detailed instructions on both approaches can be found on the Computer Science support pages.

Warning

If you are connecting from off-campus, you will also need to connect through the K-State VPN to access the Computer Science Linux server. You can find more information about the K-State VPN on the K-State IT pages

The $ indicates a terminal prompt; you don’t need to type it. The [eid] should be replaced with your eid. This should ssh you into the CS Linux system. It will prompt you for your CS password, unless you’ve set up public/private key access.

Once in, type the command:

$ nc google.com 80

The nc is the netcat executable - we’re asking Linux to run netcat for us, and providing two command-line arguments, google.com and 80, which are the webserver we want to talk to and the port we want to connect to (port 80 is the default port for HTTP requests).

Now that a connection is established, we can stream our request to Google’s server:

GET / HTTP/1.1

The GET indicates we are making a GET request, i.e. requesting a resource from the server. The / indicates the resource on the server we are requesting (at this point, just the top-level page). Finally, the HTTP/1.1 indicates the version of HTTP we are using.

Note that you need to press the return key twice after the GET line, once to end the line, and the second time to end the HTTP request. Pressing the return key in the terminal enters the CRLF character sequence (Carriage Return & Line Feed) the HTTP protocol uses to separate lines

Once the second return is pressed, a whole bunch of text will appear in the terminal. This is the HTTP Response from Google’s server. We’ll take a look at that next.

Reading the Response

Scroll up to the top of the request, and you should see something like:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 16 Jan 2019 15:39:33 GMT

Expires: -1

Cache-Control: private, max-age=0

Content-Type: text/html; charset=ISO-8859-1

P3P: CP="This is not a P3P policy! See g.co/p3phelp for more info."

Server: gws

X-XSS-Protection: 1; mode=block

X-Frame-Options: SAMEORIGIN

Set-Cookie: 1P_JAR=2019-01-16-15; expires=Fri, 15-Feb-2019 15:39:33 GMT; path=/; domain=.google.com

Set-Cookie: NID=154=XyALfeRzT9rj_55NNa006-Mmszh7T4rIp9Pgr4AVk4zZuQMZIDAj2hWYoYkKU6Etbmjkft5YPW8Fens07MvfxRSw1D9mKZckUiQ--RZJWZyurfJUyRtoJyTfSOMSaniZTtffEBNK7hY2M23GAMyFIRpyQYQtMpCv2D6xHqpKjb4; expires=Thu, 18-Jul-2019 15:39:33 GMT; path=/; domain=.google.com; HttpOnly

Accept-Ranges: none

Vary: Accept-Encoding

<!doctype html>...The first line indicates that the server responded using the HTTP 1.1 protocol, the status of the response is a 200 code, which corresponds to the human meaning “OK”. In other words, the request worked. The remaining lines are headers describing aspects of the request - the Date, for example, indicates when the request was made, and the path indicates what was requested. Most important of these headers, though, is the Content-Type header, which indicates what the body of the response consists of. The content type text/html means the body consists of text, which is formatted as HTML – in other words, a webpage.

Everything after the blank line is the body of the response - in this case, the page content as HTML text. If you scroll far enough through it, you should be able to locate all of the HTML elements in Google’s search page.

That’s really all there is with a HTTP request and response. They’re just streams of data. A webserver just receives a request, processes it, and sends a response.