The New Science of Learning

Terry Doyle and Todd Zakrajsek explore the implications of mindsets and other understandings of the learning process emerging from cognitive science in their book The New Science of Learning: How to Learn in Harmony with your Brain, which they specifically wrote for college-age learners. I would encourage you to read this book. But I’ll offer a brief summary here:

Sleep

Perhaps the most impactful thing you can do to improve your learning is to get high-quality sleep. It is during sleep that your brain consolidates the memories of the day (including what you were learning) into long-term storage. Insufficient sleep has a large negative impact on this process, resulting in lost or inaccessible memories.

The three stages of memory processing are encoding, storage, and retrieval. All three are affected in different ways by the amount of sleep you get. It is difficult to encode new learning when you are tired and unable to pay attention to the information. In fact, when you are sleep deprived, it becomes more difficult to learn new information the longer you are awake. Similarly, without the proper amount of sleep, storage of new memories will be disrupted. The third stage of memory processing is the recall phase (retrieval). During retrieval, the memory is accessed and re-edited. This is often the most important stage, as learned information is of limited value if it can't be recalled when needed, for example, for an exam. [...] Converging scientific evidence, from the molecular to the phenomenological, leaves little doubt that memory reprocessing "offline," that is, during sleep is an important component of how our memories are formed, shaped, and remembered.Dolye and Zakrajsek, 2013, pp. 21-22

The NIH recommends 7.5 to 9 hours of sleep nightly. Individuals can vary greatly in their sleep needs, and may have different sleep patterns known as “chronotypes” which are the basis for stereotypes like ‘morning people’ or ’night owls’. It is important to understand your own sleep patterns to be able to adapt your study and sleep habits to maximize your learning effectiveness. Doyle and Zakrajsek offer advice to tailor your sleep and study patterns, as well as how to deal with ‘sleep debt’ - the learning penalty incurred when you were unable to get enough rest.

Info

Caffeine and alcohol, especially when consumed in large quantities, disrupt your ability to sleep effectively, and therefore your ability to learn.

Exercise

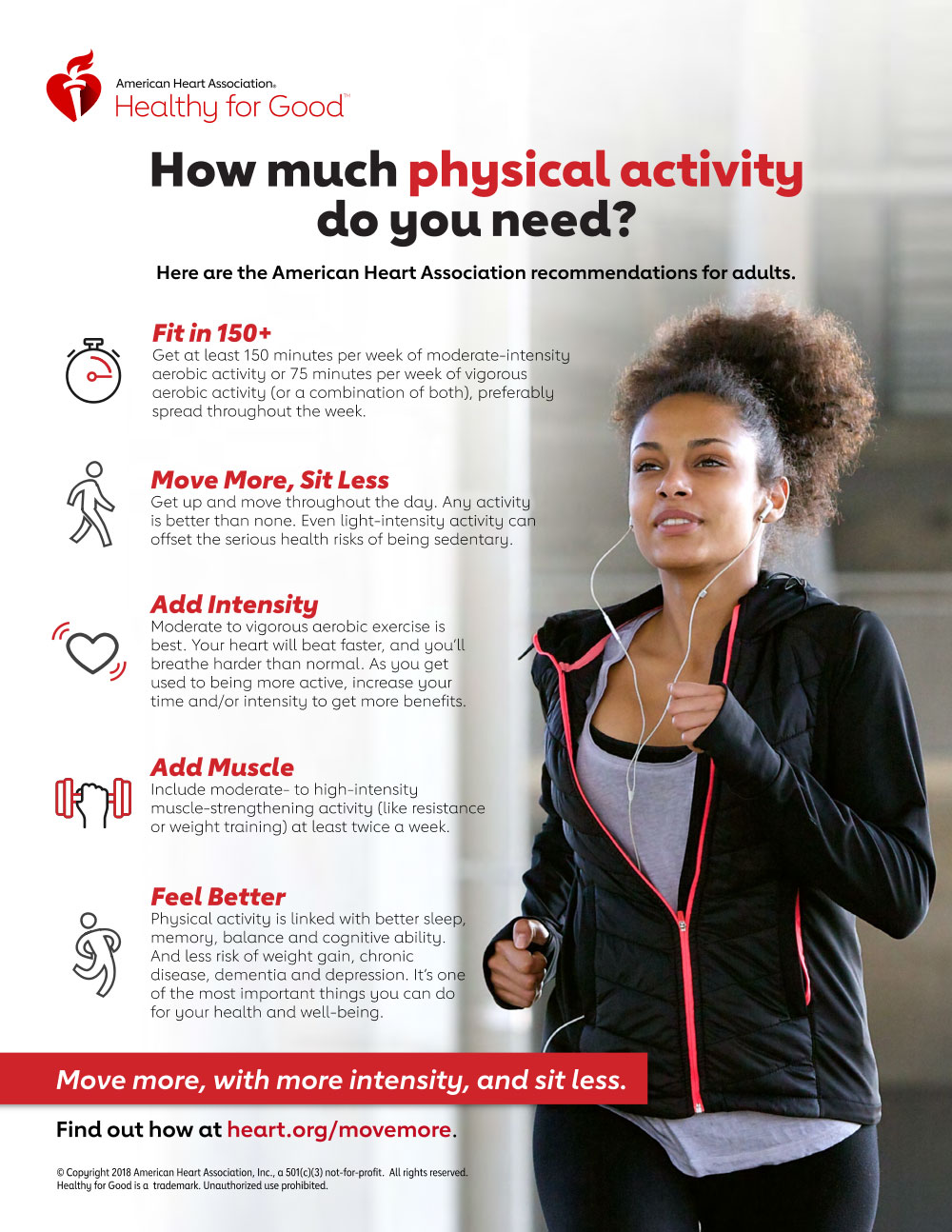

Exercise plays a surprisingly important role in learning. When you exercise - especially aerobic exercise (the kind that gets your heart rate up), your body releases extra neurochemicals and proteins that are used by the brain cells to communicate. This rush of extra resources improves your ability to learn new concepts and skills.

In addition to getting this regular exercise, you should periodically get up from your computer and walk around, or even better, adopt a standing desk. The human body is not meant to sit for extended periods of time. Doing so can lead to blood pooling in the buttocks and thighs and increases dramatically your risk of heart attack and stroke.

The Senses

As memories are encoded, they draw upon all the senses involved in the experience. Research is starting to show that involving multiple senses in a learning activity can improve the learning. This is one reason I sprinkle these readings with images and videos. It is also one of the reasons I like using Cognitive Apprenticeship in my teaching. By showing you the code I am writing (seeing), and talking about what and why I am doing it (hearing), and having you write the same code (touching), we are engaging multiple senses for a stronger learning experience.

You can also leverage this in your own learning efforts. Creating concept maps connecting the ideas you are learning in this and other CS courses engages you visually with the learning, and also encourages your brain to recognize and utilize those connections to strengthen your reasoning about them. Annotating your textbooks engages you in both reading (seeing) and touching (writing), and helps you reflect more strongly on what you are studying. Try printing out the pages of this textbook as you read them, and make your own annotations in the margins and put it into a three-ring binder. It will improve your learning and give you a physical copy of the text when you’re done!

Patterns

The human brain is built to recognize and process patterns. Explicitly seeking patterns in what you’re doing can therefore help your learning. And programming is chock full of patterns! Consider if I asked you to write some code to add one to each element in an array. What would you do? Possibly a for loop like this:

for(int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++) {

array[i] += 1;

}But what if I asked you to halve the value instead? perhaps:

for(int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++) {

array[i] /= 2;

}Notice the parts that stay the same? We call this pattern iteration, and use it constantly. Moreover, the syntax of the for loop itself is a pattern. In fact, for loops were developed because of another pattern programmers found themselves using regularly:

int i = 0;

while(i < array.Length) {

// DO SOMETHING WITH ARRAY

i++;

}Notice the three statements int i = 0;, i < array.Length, and i++;? These are the three parts of a for loop! When programmers found themselves using this pattern over and over again, they added new syntax to programming languages to simplify writing it1. In fact, the reason we use the semicolon to separate the three parts of a for loop is because they were originally separate statements in this while loop construction.

We also can apply this pattern recognition on similar, but unfamiliar formulations. Consider this code:

for(int i = array.Length-1; i >= 1; i--) {

array[i] += array[i-1];

}What does it do?

You likely noticed that it iterates through an array, but not forward through the array but rather backwards. And at each step we increase the value of an item by the value of the item before it. Could we rewrite this code as a forward iteration?

Memory

We already talked about the role of sleep in memory formation, but Doyle and Zakrajsek go deeper into how memories form and how that can be enhanced in the context of college life. For example, cognitive science has shown that parts of the brain responsible for memory formation remain active up to an hour after the learning experience (i.e. a lecture) has ended. So the common practice of scheduling your classes back-to-back may be impacting your ability to learn in the earlier classes!

Research has also shown that distributed practice is crucial to reinforcing and making available memories involved in skills as well as conceptual reasoning. The process of using the skill, or recalling the knowledge at regular intervals helps ‘settle’ the learning into our minds. In contrast, the practice of cramming may help us recall answers for an exam, but shortly after those answers will be lost to us, as the memories we formed were short-term. This is also why this class, as well as your math and physics courses emphasize solving problem after problem. It isn’t that we want to torture you - it’s that this continual practice is what helps you to learn the skills you’re developing.

Elaboration is another key to strengthening memory and recall. This involves adding more nuanced understandings to what you already know. For example, in this class we’re revisiting programming syntax that you’ve already learned, and I’ll be introducing new ideas and concepts that tie into that. Just like the example of how a for loop is nothing more than syntactic sugar for a specific while loop formulation. Do you need to know that? Probably not. But learning about it helps reinforce your understandings of how both kinds of loops operate, and that can make you a more proficient programmer.

Do you study while watching YouTube or conversing with friends? You might be interested to know that multitasking has a significant impact on memory formation:

When you shift task while working on something that requires thinking, such as texting your friend and listening to a lecture in class, your brain goes through a four-step process that allows you to switch your attention: (a) shift alert, (b) rule activation for task 1, (c) disengagement, (d) rule activation for task 2. This process is repeated every time you switch tasks that involve thinking, and you never get better or faster at it. You may have noticed that when you try to do two thinking tasks at the same time, you cannot complete both simultaneously, as the brain must shut down one task before working on the other. [...R]esearch demonstrates that individuals who shift tasks make 50% more errors and spend at least 50% more time on both tasks.Dolye and Zakrajsek, 2013, p. 79

Stress also has an impact on memory formation - even minor stressful events can cause the release of hormones that disrupt the brain’s learning process. Exercise is the best counter to this issue, both helping repair the damage from stress and prevent it from occurring.

We call this common practice of adding new syntax to a language to simplify writing commonly used patterns syntactic sugar, as it’s not strictly necessary, but makes the process of writing programs so much sweeter. ↩︎