Branches

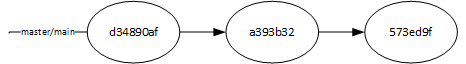

Branches are a powerful mechanisms for working on different versions of your code. The name “branch” is derived from visualizing a repository as a tree structure, with each commit being a node in the tree. For a simple repository, this tree structure is pretty boring - just a straight line as each node has only one child:

This default branch was historically named “master”, though recent practice has shifted to using the term “main”. GitHub provides guidance and support for renaming existing project branches.

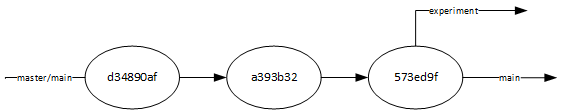

At any node in the commit tree, we could create a new branching point with the command git branch [branchname] where we supply the branch name. The branch starts with exactly the same code as the current commit to main (or whatever branch we are branching from). Then we can check out the branch with git checkout [branchname], using the name we supplied. Let’s create and check out a branch named “experiment” in our above example:

$ git branch experiment

$ git checkout experimentWe now have a new branch, experiment, branching from commit 573ed9f:

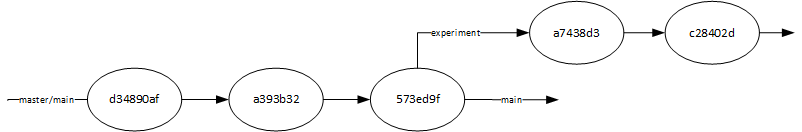

While “experiment” is the checked out branch, any commits we make are placed on it instead of the main branch. Let’s assume we create two commits on the experiment branch; our tree will now look like:

We can switch back to the main branch at any point with git checkout main. When we do so, our code will be reverted back to how it was in the last commit to the main branch (commit 573ed9f). If it turns out our experiment was a flop, we can forget about the experiment branch and the changes we made to it - we’re back to a clean working build at the point before we started the experiment.

It is important to understand how commits and branches interact. When you check out a branch, the code in the repository is reverted to the last commit on that branch. And any new commits you make are saved to the currently checked out branch.

If you have uncommitted or staged changes in files, git will refuse to check out a branch until these are committed or stashed, as checking out the branch will overwrite those changes and they would be lost forever. In contrast, unstaged and ignored files are fine (as there is no committed version that will overwrite the file). Best practice is to commit your changes before switching branches, unless you want to throw the changes away.

If, on the other hand, we like the changes from the experiment, and want to add them to the main branch, we can merge those changes with the git merge [branchname] command:

$ git merge experimentThis merges the specified branch with the currently checked-out branch. Git accomplishes merging through a recursive strategy, which works very well. However, if both branches have had changes committed since the last shared commit, there is a possibility that some of those changes will overlap, and Git will not be able to determine which to use. This is called a merge conflict and must be resolved by you. See the merge conflict section later for more details.

There are a number of reasons we might want to create a branch; let’s examine some common use cases.

Prototype branches - Let’s say we wanted to try making some changes to our code that we aren’t sure will work - basically, we are creating an experimental prototype. If this experiment doesn’t end up succeeding, we would like to return to our current version of the project. This is exactly the scenario we walked through above.

Feature branches - Let’s assume you have a working program you need to add a new feature to, but you still want to be able to access the working code. In this case, you can create a branch to work on that feature. That way, when your feature is only partially done, you can still switch back to your main branch and fix a bug, etc., without needing to remove or comment out your half-written feature code.

Personal branches - Let’s say you’re working with a team. You want to make sure that the main branch is always clean, ready-to-go code, and you don’t want to have to deal with your teammate’s half-written code (nor they with yours). Each team member can create their own branch to do their work on, and when it is tested and ready, merge that code into the main branch.

Each of these approaches can (and usually is) used in conjunction with remote repositories. We’ll take a look at that next.