Remote Repositories

YouTube VideoGit bills itself as a distributed version control system. This means it has no central server. Instead, we can create copies of the repository we call remote repositories with the git clone command. These copies can be placed anywhere - in another directory on your computer, or on a different computer on your network, or a computer accessed via the internet.

GitHub is a web service that specifically hosts remote git repositories and allows you to access them through both your git client and through a web (HTML/CSS/JS) interface. It was created primarily to provide a place to host publicly-accessible, open-source projects, though you can also use it to create private repositories. It is not the only such service available; BitBucket is a similar website more focused on closed-source projects, and the popular GitLab is an open-source server for hosting Git projects you can install on your own systems. The Computer Science department at Kansas State University runs its own GitLab server to host projects developed as part of our research and extension mission.

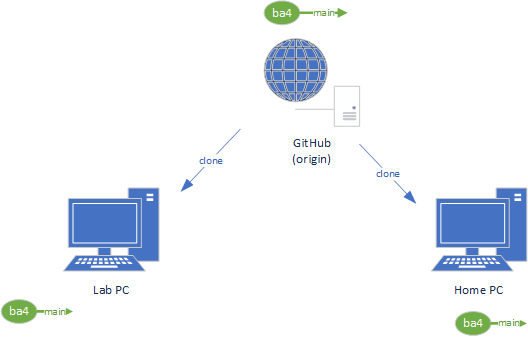

At this point in your learning, you will likely be using a repository hosted on GitHub (usually created by GitHub classroom when you accept an assignment) as a remote repository you are cloning to one or more local repositories. For example, you’ll likely clone your project on both your home computer and a lab computer so you can work in both locations.

A clone is a copy of the project in its current state, including the hidden .git folder. This means it is also a complete git repository! The code will be in the same state as that of the currently active branch of the repo it was cloned from (for a project cloned from GitHub, this would be the main/master branch).

Warning

While the cloned repository is a copy of an existing repository, it will not contain unstaged or ignored files or directories, as these are not tracked by Git.

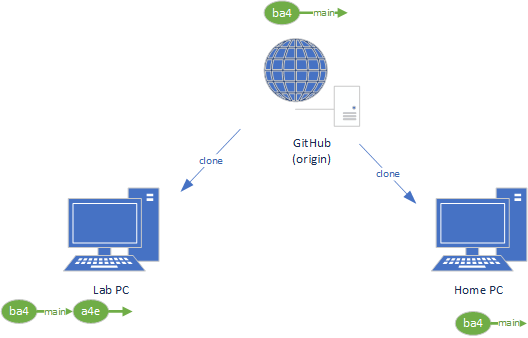

Thus, in our diagram above, the home, lab, and GitHub copies of our repository all start exactly the same, with commit ba4. But if we make and commit changes to one of those repositories, that repository will be ahead of the other repositories, which will not have that commit. We can see this in the diagram below, where we have added commit a4e to the repository on our Lab PC:

To get this same commit on our other remote repositories, we’ll use push and pull commands.

Pushing

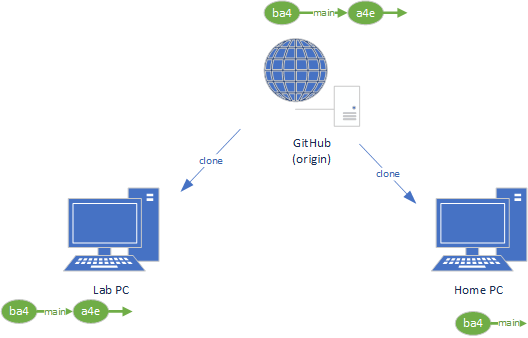

We can push commits from one repository to another one with a git push command. To use this command, we need to know the location of the remote repository, and what branch we want to push our changes to. When we clone an existing repository, Git automatically saves the location of that repository and gives it the name origin. Thus, we can copy our commit a4e from our Lab PC repository to GitHub with the git push command:

$ git push origin mainThis pushes our new commit to the GitHub repository, so it now also has that commit:

Because GitHub does not have a reference to our Home PC’s repository, we can’t push the commit there. Instead, we’ll need to pull it directly from our home computer.

Pulling

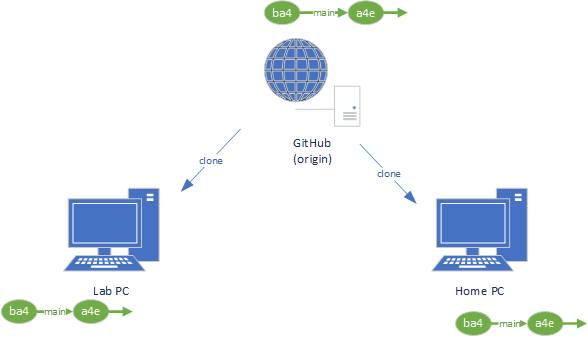

As the repository on our home PC is also a clone of the GitHub repository, it kept track of the location of it using the name origin as well. So we can pull commits from that location (GitHub) using the git pull command:

$ git pull origin mainThis copies any commits on the GitHub repository into the Home PC repository:

Warning

If you push or pull changes to a repository that has extra commits, Git merges the extra commits with the pushed ones (as with the merge command). This can introduce the possibility of merge conflicts when Git is uncertain how to best combine two changes. These must be resolved by you as described in the merge conflict section. For this reason, it is always best practice to pull changes into your local branch, fix any merge conflicts, create a new commit, and only then push it to the remote repository. This ensures that the main branch code is always in good shape.

Remote Repositories

You can actually set up as many remote repositories as you want. In the diagram above, it would be possible to push or pull from the Lab PC to the Home PC directly, provided you had a publicly accessible URL for both (as we normally don’t have static IP addresses for home networks, this is unlikely). You can add an additional remote repository with git remote add [name] [url].

This can be helpful if you have a project you’ve started on your home machine and want to push to GitHub. Create an empty project on GitHub (it must be completely empty, so don’t create a default readme or license file). Then copy the clone URL and use it in your local Git command:

git remote add origin [remote url]where [remote url] is the GitHub clone url. After you’ve done this, you can push your project to GitHub normally.

You can also list all remote repositories in a repo with:

git remote -vRemote Branches

You probably noticed in our push and pull examples above, we specified the main branch. You can also pull or push from other branches, i.e. if you had an experiment branch on your remote repository origin you could pull it with:

git pull origin experimentThat would merge the experiment branch into the branch you currently have checked out.

Most often, we want to have our remote and local branches correspond to one another. In that case, we can first fetch all remote changes (without merging them into our local repository), which will also fetch any new remote branches. Then, we can create a new local branch that is synchronized to a new remote upstream branch. For example, suppose there is an experiment branch in our remote repository and we wish to create a new local experiment branch to track it. We can do:

git fetch

git checkout -b experiment origin/experimentAfter these commands, we have created the new local experiment branch which is currently synchronized with the remote experiment branch, and have checked out that new branch. As we make changes, we can use the git push and git pull shorthands, which will push and pull between the local experiment and remote experiment branches.