Browser Requests

Before we get too deep in the details of what a request is, and how it works, let’s explore the primary kind of request you’re already used to making - requests originating from a browser. Every time you use a browser to browse the Internet, you are creating a series of HTTP (or HTTPS) requests that travel across the networks between you and a web server, which responds to your requests.

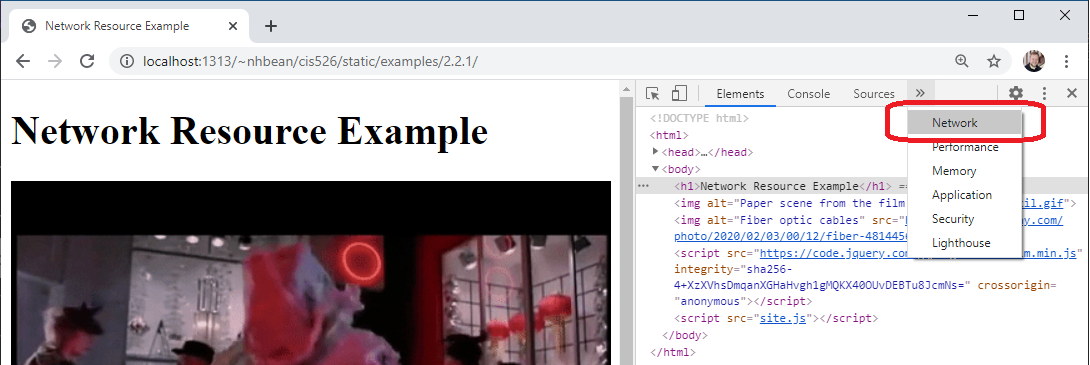

To help illustrate how these requests are made, we’ll once again turn to our developer tools. Open the example page this link. On that tab, open your developer tools with CTRL + SHIFT + i or by right-clicking the page and selecting “Inspect” from the context menu. Then choose the “Network” tab:

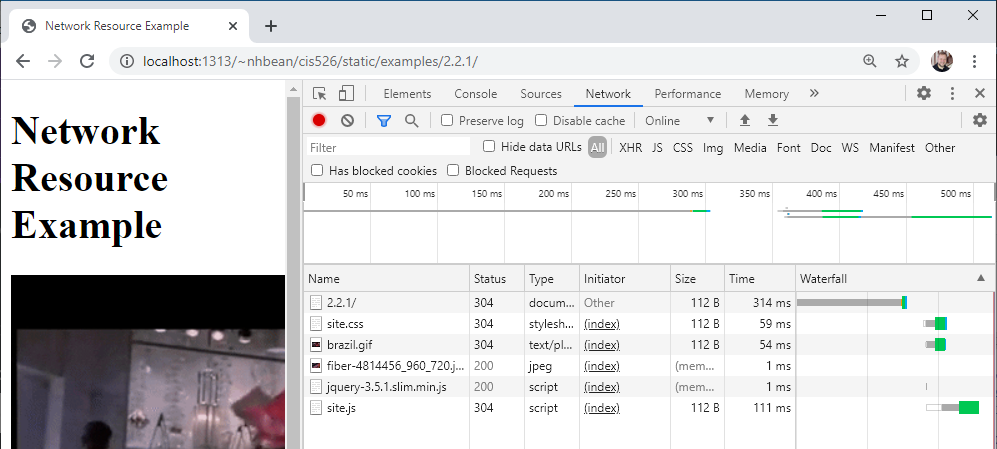

The network tab displays details about each request the browser makes. Initially it will probably be empty, as it does not log requests while not open. Try refreshing the page - you should see it populate with information:

The first entry is the page itself - the HTML file. But then you should see entries for site.css, brazil.gif, fiber-4814456_960_720.jpg, jquery-3.5.1.slim.min.js, and site.js. Each of these entries represents an additional resource the browser fetched from the web in order to display the page.

Take, for example, the two images brazil.gif and fiber-4814456_960_720.jpg. These correspond to <img> tags in the HTML file:

<img alt="Paper scene from the film Brazil" src="brazil.gif"/>

<img alt="Fiber optic cables" src="https://cdn.pixabay.com/photo/2020/02/03/00/12/fiber-4814456_960_720.jpg"/>

The important takeaway here is that the image is requested separately from the HTML file. As the browser reads the page and encounters the <img> tag, it makes an additional request for the resource supplied in its src attribute. When that second request finishes, the downloaded image is added to the web page.

Notice too that while one image was on our webserver, the other is retrieved from Pixabay.com’s server.

Similarly, we have two JavaScript files:

<script src="https://code.jquery.com/jquery-3.5.1.slim.min.js" integrity="sha256-4+XzXVhsDmqanXGHaHvgh1gMQKX40OUvDEBTu8JcmNs=" crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

<script src="site.js"></script>As with the images, one is hosted on our website, site.js, and one is hosted on another server, jquery.com.

Both the Pixabay image and the jQuery library are hosted by a Content Delivery Network- a network of proxy servers that are distributed geographically in such a way that a request for a resource they hold can be processed from a nearby server. Remember that the theoretical maximum speed for internet transmissions is the speed of light (for fiber optics) or electrons in copper wiring. Communication is further slowed at each network switch encountered. Serving files from a nearby server can prove very efficient at speeding up page loads because of the shorter distance and smaller number of switches involved.

A second benefit of using a CDN to request the JQuery library is that if the browser has previously downloaded the library when visiting another site it will have cached it. Using the cached version instead of making a new request is much faster. Your app will benefit by faster page loads that use less bandwidth.

Notice too that the jQuery <script> element also uses the integrity attribute to allow the browser to determine if the library downloaded was tampered with by comparing cryptographic tokens. This is an application of Subresource Integrity, a feature that helps protect your users. As JavaScript can transform the DOM, there are incentives for malicious agents to supplant real libraries with fakes that abuse this power. As a web developer you should be aware of this, and use all the tools at your disposal to keep your users safe.

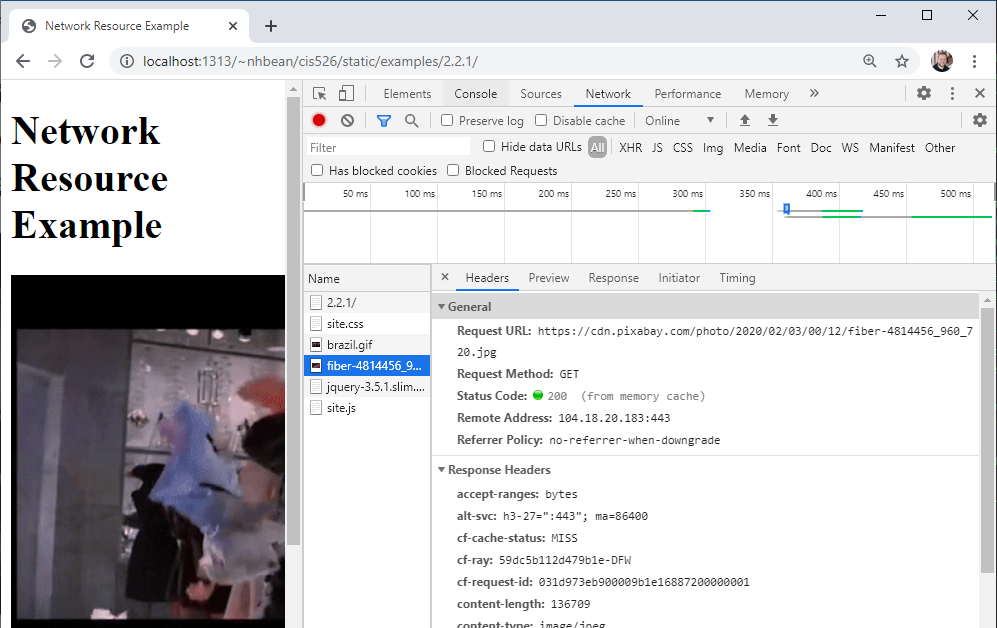

You can use the network tab to help debug issues with resources. Click on one of the requested resources, and it will open up details about the request:

Notice that it reports the status code along with details about the request and response, and provides a preview of the requested resource. We’ll cover what these all are over the remainder of this chapter. As you learn about each topic, you may want to revisit the tab with the example to see how these details correspond to what you are learning.