HTTP 2.0

You may have noticed that the earlier parts of this chapter focused on HTTP version 1.1, while mentioning version 2.0. You might wonder why we didn’t instead look at version 2.0 - and it’s a valid question.

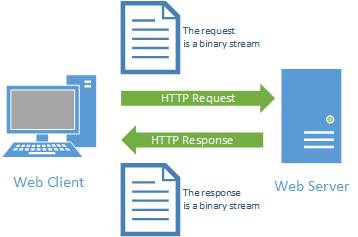

In short, HTTP 2.0 was created to make the request-response pattern of the web more efficient. One method it uses to do so is switching from text-based representations of requests and responses to binary-based representations. As you probably remember from working with File I/O, binary files are much smaller than the equivalent text file. The same is true of HTTP requests and responses. But the structure of HTTP 2.0 Requests and Responses are identical to HTTP 1.1 - they are simply binary (an hence, harder to read).

But this is not the only improvement in HTTP 2.0. Consider the request-response pattern we discussed earlier in the chapter:

To display a webpage, the browser must first request the page’s HTML data. As it processes the returned HTML, it will likely encounter HTML <img>, <link>, and <src> tags that refer to other resources on the server. To get these resources, it will need to make additional requests. For a modern webpage, this can add up quickly! Consider a page with 20 images, 3 CSS files, and 2 JavaScript files. That’s 25 separate requests!

One of the big improvements between HTTP/1.0 and HTTP/1.1 was that HTTP/1.1 does not close its connection to the server immediately - it leaves a channel open for a few seconds. This allows it to request these additional files without needing to re-open the connection between the browser and the server.

HTTP/2.0 takes this thought a step farther, by trying to anticipate the browser’s additional requests. In the HTTP/2.0 protocol, when a browser requests an HTML page, the server can push the additional, linked files as part of the response. Thus, the entire page content can be retrieved with a single request instead of multiple, separate requests. This minimizes network traffic, allowing the server to handle more requests, and speeds up the process of rendering pages on a client’s machine.