Statelessness and Scaling

One final point to make about Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol. It is a stateless protocol. What this means is that the server does not need to keep track of previous requests - each request is treated as though it was the first time a request has been made.

This approach is important for several reasons. One, if a server must keep track of previous requests, the amount of memory required would grow quickly, especially for popular web sites. We could very quickly grow past the memory capacity of the server hardware, causing the webserver to crash.

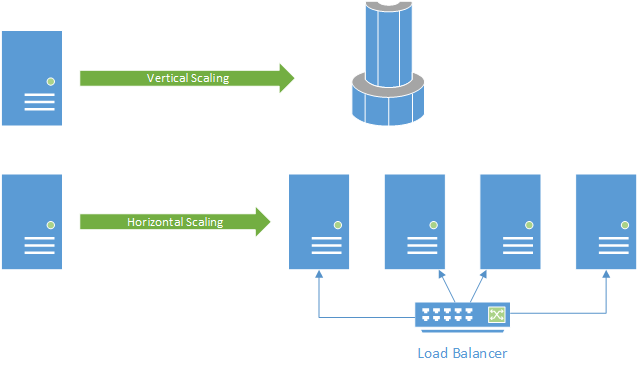

A second important reason is how we scale web applications to handle more visitors. We can do vertical scaling - increasing the power of the server hardware - or horizontal scaling - adding additional servers to handle incoming requests. Not surprisingly, the second option is the most cost-effective. But for it to work, requests need to be handed quickly to the first available server - there is no room for making sure a subsequent request is routed to the same server.

Thus, HTTP was designed as a stateless protocol, in that each new HTTP request is treated as being completely independent from all previous requests from the same client. This means that when using horizontal scaling, if the first request from client BOB is processed by server NANCY, and the second request from BOB is processed by server MARGE, there is no need for MARGE to know how NANCY responded. This stateless property was critical to making the world-wide-web even possible with the earliest internet technologies.

Of course, you probably have experience with websites that do seem to keep track of state - i.e. online stores, Canvas, etc. One of the challenges of the modern web was building state on top of a stateless protocol; we’ll discuss the strategies used to do so in later chapters.