Concurrency Approaches

Concurrency means “doing more than one thing at the same time.” In computer science, concurrency can refer to (1) structuring a program or algorithm so that it can be executed out-of-order or in partial order, or (2) actually executing computations in parallel. In modern-day programming, we’re often talking about both. But to help us develop a stronger understanding, let’s look at the two ideas one-at-a-time, and then bring it together.

Concurrency

One of the earliest concurrency problems computer science dealt with was the efficient use of early computers. Consider a mainframe computer like the PDP-1, once a staple of the university computer science department. In 1963, the base price of a PDP-1 was $120,000. Adjusted for inflation, this would be a price of a bit more than one million dollars in 2020! That’s a pretty big investment! Any institution, be it a university, a corporation, or a government agency that spent that kind of money would want to use their new computer as efficiently as possible.

Consider when you are working on a math assignment and using a calculator. You probably read your problem carefully, write out an equation on paper, and then type a few calculations into your calculator, and copy the results to your paper. You might write a few lines as you progress through solving the problem, then punch a new calculation into your calculator. Between computations, your calculator is sitting idle - not doing anything. Mainframe computers worked much the same way - you loaded a program, it ran, and spat out results. Until you loaded a new program, the mainframe would be idle.

Batch Processing

An early solution was the use of batch processing, where programs were prepared ahead of time on punch-card machines or the like, and turned over to an IT department team that would then feed these programs into the computer. In this way, the IT staff could keep the computer working as long as there was batched work to do. While this approach kept the computer busy, it was not ideal for the programmers. Consider the calculator example - it would be as if you had to write out your calculations and give them to another person to enter into the calculator. And they might not get you your results for days!

Can you imagine trying to write a program that way? In the early days that was exactly how CS students wrote programs - they would write an entire program on punch cards, turn it in to the computer staff to be batched, and get the results once it had been run. If they made a mistake, it would require another full round of typing cards, turning them in, and waiting for results!

Batch processing is still used for some kinds of systems - such as the generation of your DARS report at K-State, for sending email campaigns, and for running jobs on Beocat and other supercomputers. However, in mainframe operations it quickly was displaced by time sharing.

Time Sharing

Time-sharing is an approach that has much in common with its real-estate equivalent that shares its name. In real estate, a time-share is a vacation property that is owned by multiple people, who take turns using it. In a mainframe computer system, a time sharing approach likewise means that multiple people share a single computer. In this approach, terminals (a monitor and keyboard) are hooked up to the mainframe. But there is one important difference between time-sharing real estate and computers, which is why we can call this approach concurrent.

Let’s return to the example of the calculator. In the moments between your typing an expression and reading the results, another student could type in their expression, and get their results. A time-sharing mainframe does exactly that - it take a few fractions of a second to advance each users’ program, switching between different users at lightning speed. Consider a newspaper where twenty people might we writing stories at a given moment - each terminal would capture key presses, and send them to the mainframe when it gave its attention, which would update the text editor, and send the resulting screen data back to the terminal. To the individual users, it would appear the computer was only working with them. But in actuality it was updating all twenty text editor program instances in real-time (at least to human perception).

Like batch processing, time-sharing is still used in computing today. If you’ve used the thin clients in the DUE 1114 lab, these are the current-day equivalents of those early terminals. They’re basically a video card, monitor, and input device that are hooked up to a server that runs multiple VMs (virtual machines), one for each client, and switches between them constantly updating each.

Multitasking

The microcomputer revolution did not do away with the concept. Rather, modern operating systems still use the basic concept of the approach, though in the context of a single computer it is known as multitasking. When you write a paper now, your operating system is switching between processes in much the same way that time-sharing switched between users. It will switch to your text editor, processing your last keystroke and updating the text on screen. Then it will shift to your music player and stream the next few thousand bytes of the song you’re listening to the sound card. Then it will switch to your email program which checks the email server and it will start to notify you that a new email has come in. Then it will switch back to your text editor.

The thin clients in DUE 1114 (as well as the remote desktops) are therefore both time-sharing between VMs and multitasking within VMs.

Parallel Processing

The second approach to concurrency involves using multiple computers in parallel. K-State’s Beocat is a good example of this - a supercomputer built of a lot of individual computers. But your laptop or desktop likely is as well; if you have a multi-core CPU, you actually have multiple processors built into your CPU, and each can run separate computational processes. This, it is entirely possible that as you are writing your term paper the text editor is running on one processor, your email application is using a second one, and your music is running on a third.

In fact, modern operating systems use both multitasking and parallel processing in tandem, spreading out the work to do across however many cores are available, and swapping between active processes to on those cores. Some programs also organize their own computation to run on multiple processors - your text editor might actually be handling your input on one core, running a spellcheck on a second, and a grammar check on a third.

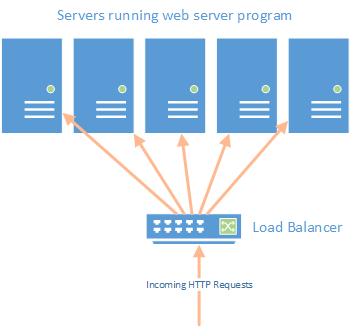

Remember our earlier discussion about scaling web servers? This is also a parallel processing approach. Incoming HTTP requests are directed by a load balancer to a less-busy server, and that server formulates the response.

Multithreading

Individual programs can also be written to execute on multiple cores. We typically call this approach Multithreading, and the individually executing portions of the program code threads.

These aren’t the only ways to approach concurrency, but they are ones we commonly see in practice. Before we turn our attention to how asynchronous processes fit in though, we’ll want to discuss some of the challenges that concurrency brings.