Asynchronous Programming

In asynchronous programming, memory collisions are avoided by not sharing memory between threads. A unit of work that can be done in parallel is split off and handed to another thread, and any data it needs is copied into that threads’ memory space. When the work is complete, the second thread notifies the primary thread if the work was completed successfully or not, and provides the resulting data or error.

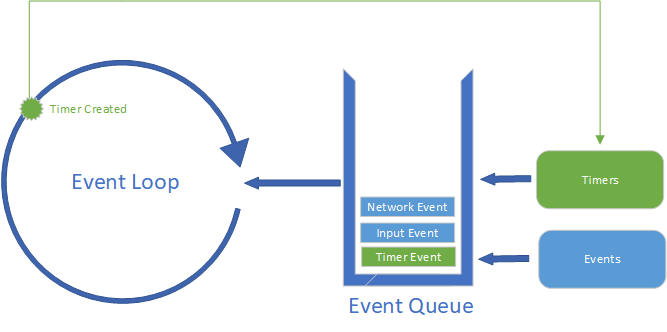

In JavaScript, this notification is pushed into the event queue, and the main thread processes it when the event loop pulls the result off the event queue. Thus, the only memory that is shared between the code you’ve written in the Event Loop and the code running in the asynchronous process is the memory invovled in the event queue. Keeping this memory thread-safe is managed by the JavaScript interpreter. Thus, the code you write (which runs in the Event Loop) is essentially single-threaded, even if your JavaScript application is using some form of parallel processing!

Let’s reconsider a topic we’ve already discussed with this new understanding - timers. When we invoke setTimer(), we are creating a timer that is managed asynchronously. When the timer elapses, it creates a timer ’event’ and adds it to the event queue. We can see this in the diagram below.

However, the timer is not actually an event, in the same sense that a 'click' or 'keydown' event is… in that those events are provided to the browser from the operating system, and the browser passes them along into the JavaScript interpreter, possibly with some transformation. In contrast, the timer is created from within the JavaScript code, though its triggering is managed asynchronously.

In fact, both timers and events represent this style of asynchronous processing - both are managed by creating messages that are placed on the event queue to be processed by the interpreter. But the timer provides an important example of how asynchronous programming works. Consider this code that creates a timer that triggers after 0 milliseconds:

setTimeout(()=>{

console.log("Timer expired!");

}, 0);

console.log("I just set a timer.");What will be printed first? The “Timer expired!” message or the “I just set a timer.” message?

See for yourself - try running this code in the console (you can click the “console” tab below to open it).

The answer is that “I just set a timer” will always be printed first, because the second message won’t be printed until the event loop pulls the timer message off the queue, and the line printing “I just set a timer” is executed as part of this pass in the event loop. The setTimeout() and setInterval() functions are what we call asynchronous functions, as they trigger an asynchronous process. Once that process is triggered, execution immediately continues within the event loop, while the triggered process runs in parallel. Asynchronous functions typically take a function as an argument, known as a callback function, which will be triggered when the message corresponding to the asynchronous process is pulled off the event queue.

Warning

Any code appearing after a call to an asynchronous function will be executed immediately after the asynchronous function is invoked, regardless of how quickly the asynchronous process generates its message and adds it to the event queue.

As JavaScript was expanded to take on new functionality, this asynchronous mechanism was re-used. Next, we’ll take a look at an example of this in the use of web workers.