Web Workers

As JavaScript began to be used to add more and more functionality to web applications, an important limitation began to appear. When the JavaScript interpreter is working on a big task, it stays in the event loop a long time, and does not pull events from the event queue. The result is the browser stops responding to user events… and seems to be frozen. On the other hand - some programs will never end. Consider this one:

while(true) {

console.log("thinking...");

}This loop has no possible exit condition, so if you ran it in the browser, it would run infinitely long… and the page would never respond to user input, because you’d never pull any events of the event queue. One of the important discoveries in computer science, the Halting Problem tackles exactly this issue - and Alan Turing’s proof shows that a program to determine if another program will halt for all possible programs cannot be written.

Thus, browsers instead post warning messages after execution has run for a significant amount of time, like this one:

So, if we want to do a long-running computation, and not have the browser freeze up, we needed to be able to run it separately from the thread our event loop is running on. The web worker provides just this functionality.

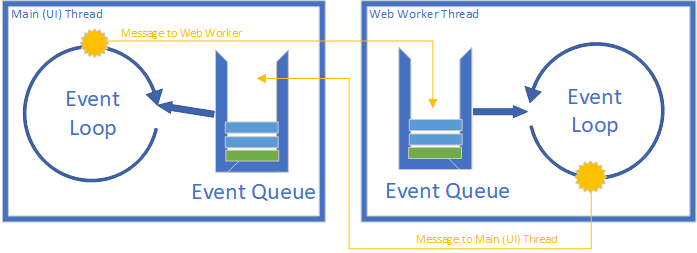

A web worker is essentially another JavaScript interpreter, running a script separate from the main thread. As an interpreter, it has its own event loop and its own memory space. Workers and the main thread can communicate by passing messages, which are copied onto their respective event queues. Thus, communication between the threads is asynchronous.

An Example

You can see an example of such a web worker by using this link to open another tab in your browser. This example simulates a long-running process of n seconds either in the browser’s main thread or in a web worker. On the page is also three colored squares that when clicked, shift colors. Try changing the colors of the squares while simulating a several-second process in both ways. See how running the process on the main thread freezes the user interface?

Using Web Workers

Web workers are actually very easy to use. A web worker is created by constructing a Worker object. It takes a single argument - the JavaScript file it will execute (which should be hosted on the same server). In the example, this is done with:

// Set up the web worker

var worker = new Worker('stall.js');The stall.js file contains the script the worker will execute - we’ll take a look at it in a minute.

Once created, you can attach a listener to the Worker. It has two events:

message- a deserialized message sent from the web workermesageerror- a message sent from the web worker that was not serializable

You can use worker.addEventListener() to add these, or you can assign your event listener to the event handler properties. Those properties are:

Worker.onmessage- triggered when themessageevent happensWorker.onmessageerror- triggered when themessageerrorevent happens

Additionally, there is an error handler property:

Worker.onerror

Which triggers when an uncaught error occurs on the web worker.

In our example, we listen for messages using the Worker.onmessage property:

// Set up message listener

worker.onmessage = function(event){

// Signal completion

document.querySelector('#calculation-message').textContent = `Calculation complete!`;

}If the message was successfully deserialized, it’s data property contains the content of the message, which can be any valid JavaScript value (an int, string, array, object, etc). This gives us a great deal of flexibility. If you need to send more than one type of message, a common strategy is to send a JavaScript object with a type property, and additional properties as needed, i.e.:

var messageData1 = {

type: "greeting",

body: "Hello! It's good to see you."

}

var messageData2 = {

type: "set-color",

color: "#ffaacc"

}We can send messages to the web worker with Worker.postMessage(). Again, these messages can be any valid JavaScript value:

worker.postMessage("Foo");

worker.postMessage(5);

worker.postMessage({type: "greetings", body: "Take me to your leader!"});In our example, we send the number of seconds to wait as an integer parsed from the <input> element:

// Get the number to calculate the Fibonacci number for and convert it from a string to a base 10 integer

var n = parseInt(document.querySelector('#n').value, 10);

// Stall for the specified amount of time

worker.postMessage(n);Whatever data we send as the message is copied into the web worker’s memory using the structured clone algorithm. We can also optionally transfer objects to the web worker instead of copying them by providing them as a second argument. This transfers the memory holding them from one thread to the other. This makes them unavailable on the original thread, but is much faster than copying when the object is large. It is used for sending objects like ArrayBuffer, MessagePort, or ImageBitmap. Transferred objects also need to have a reference in the first argument.

The Web Worker Context

For the JavaScript executing in the web worker, the context is a bit different. First, there is no document object model, as the web worker cannot make changes to the user interface. Likewise there is no global window object. However, many of the normal global functions and properties not related to the user interface are available, see functions and classes available to web workers for details.

The web worker has its own unique global scope, so any variables declared in your main thread won’t exist here. Likewise, varibles declared in the worker will not exist in the main scope either. The global scope of the worker has mirror events and properties to the Worker - we can listen for messages from the main thread using the onmessage and onmessageerror properties, and send messages back to the main thread with postMessage().

The complete web worker script from the example is:

/** @function stall

* Synchronously stalls for the specified amount of time

* to simulate a long-running calculation

* @param {int} seconds - the number of seconds to stall

*/

function stall(seconds) {

var startTime = Date.now();

var endTime = seconds * 1000 + startTime;

while(true) {

if(Date.now() > endTime) break;

}

}

/**

* Message handler for messages from the main thread

*/

onmessage = function(event) {

// stall for the specified amount of time

stall(event.data);

// Send an answer back to the main thread

postMessage(`Stalled for ${event.data} seconds`);

// Close the worker since we create a

// new worker with each stall request.

// Alternatively, we could re-use the same

// worker.

close();

};Workers can also send AJAX requests, and spawn additional web workers! In the case of spawning additional workers, the web worker that creates the child worker is treated as the main thread.

Other kinds of Web Workers

The web workers we’ve discussed up to this point are basic dedicated workers. There are also several other kinds of specialized web workers:

- Shared workers are shared between several scripts, possibly even running in different

<iframe>elements. These are more complex than a dedicated worker and communicate via ports. See MDN’s SharedWorker article for information. - Service workers act as proxy servers between the server and the web app, for the purpose of allowing web apps to be used offline. We’ll discuss these later in the semester, but you can read up on them in the mdn ServiceWorker article.

- Audio workers allow for direct scripting of audio processing within a web worker context. See the mdn AudioWorker article for details.