Event Loop & Console

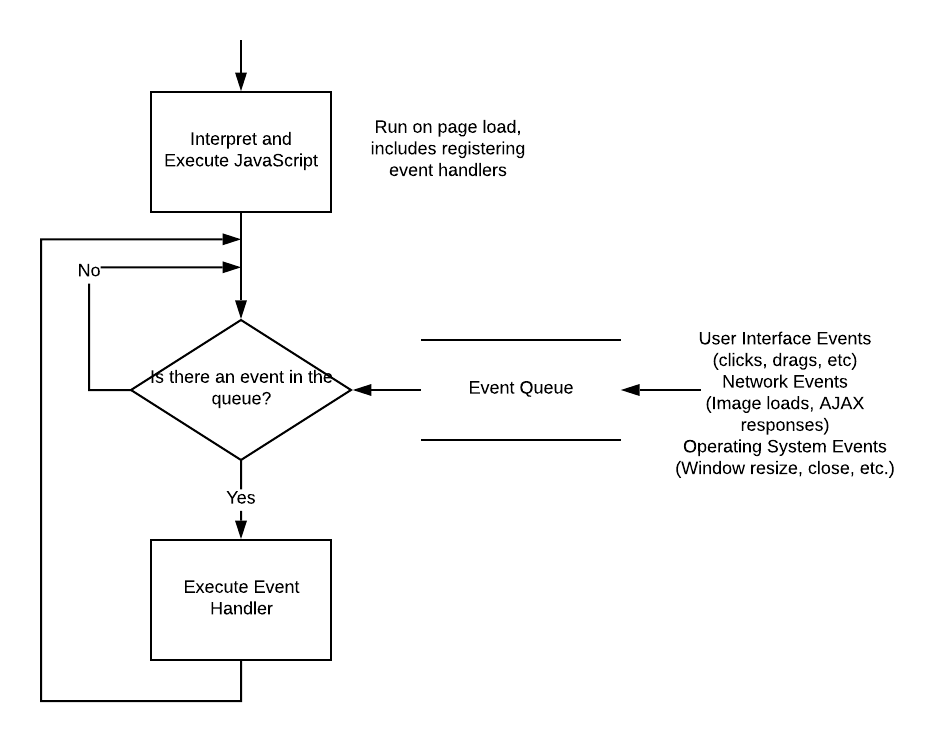

Node adopts an asynchronous event-driven approach to computing, much like JavaScript does in the browser. For example, when we set up a HTTP server in Node, we define a function to call when a HTTP request (an event) is received. As requests come in, they are added to a queue which is processed in a FIFO (first-in, first-out) manner.

In addition to events, Node implements many asynchronous functions for potentially blocking operations. For example, consider file I/O. If you write a program that needs to read a file, but when it attempts to do so the file is already open in another program, your program must wait for it to become available. In the meantime, your program is blocked, and its execution pauses. A real-world analogue would be a checkout line at a store. If the cashier is ringing up a customer and finds an item without a price tag, they may leave their station to go find the item on the shelves. While they are away, the line is blocked, everyone in line must wait for the cashier to return.

There are two basic strategies to deal with potentially blocking operations - multi-threading and asynchronous processing. A multi-threading strategy involves parallelizing the task; in our store example, we’d have additional cash registers, cashiers, and lines. Even if one line is blocked, the others continue to ring up customers. In contrast, asynchronous processing moves the potentially blocking task into another process, and continues with the task at hand. When the asynchronous process finishes, it queues its results for the main process to resume. In our store example, this would be the cashier sending another employee to find the price, suspending the sale on the register, and continuing to check out other customers while the first customer waits. When the other employee returns with a price, the cashier finishes checking out the current customer, then resumes the first customer’s transactions.

Node uses this asynchronous model to handle most potentially blocking operations (and often provides a synchronous approach as well). When possible, the asynchronous process is handled by the operating system, but the Node runtime also maintains a pool of threads to farm tasks out to.

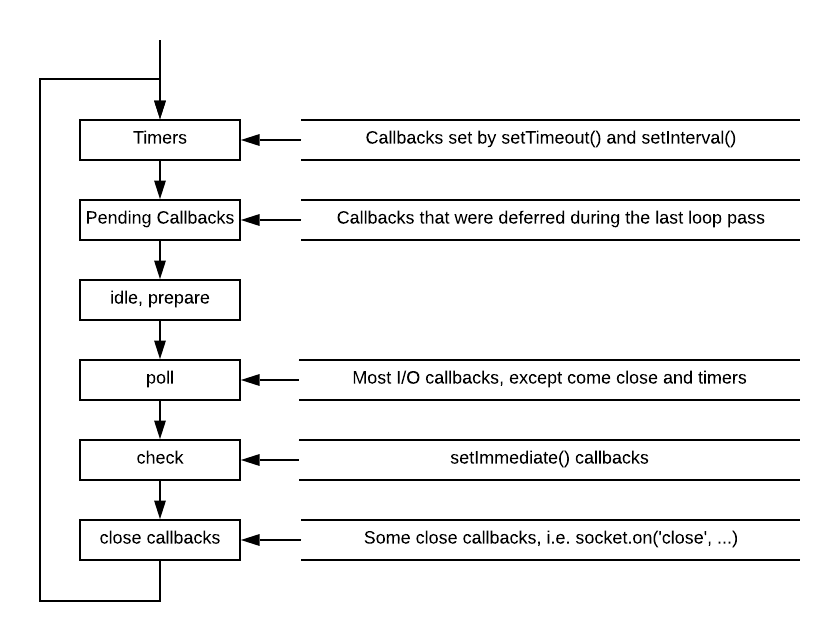

The Node event loop is divided into a series of phases - each queues the associated kinds of events and processes them in a round-robin fashion. This helps ensure that one kind of event can’t overwhelm the system:

For a more detailed breakdown of the Node event loop, check out this blog post by Daniel Khan or the Node Event Loop Documentation.

Console

To produce output on the terminal, Node provides a global instance of a Console called console that is accessible throughout the code. The typical way to produce text output on the terminal in Node is using the console.log() method.

Node actually defines multiple log functions corresponding to different log levels, indicating the importance of the message. These are (in order of severity, least to most):

console.debug()console.info()console.warn()console.error()

These are all aliases for console.log() (console.debug() and console.info()) or console.error() (console.warn() and console.error()). They don’t really do anything different, which might lead you to wonder why they exist…

But remember, JavaScript is a dynamic language, so we can re-define the console object with our own custom implementation that does do something unique with these various versions. But because they exist, they can also be used with the built-in console. This way our code can be compatible with both approaches!