Request Handling

An important aspect to recognize about how Node’s http library operates is that all requests to the server are passed to the request handler function. Thus, you need to determine what to do with the incoming request as part of that function.

Working with the Request Object

You will most likely use the information contained within the http.IncomingMessage object supplied as the first parameter to your request handler. We often use the name req for this parameter, short for request, as it represents the incoming HTTP request.

Some of its properties we might use:

The

req.methodparameter indicates what HTTP method the request is using. For example, if the method is"GET", we would expect that the client is requesting a resource like an HTML page or image file. If it were a"POST"request, we would think they are submitting something.The

req.urlparameter indicates the specific resource path the client is requesting, i.e."/about.html"suggests they are looking for the “about” page. The url can have more parts than just the path. It also can contain a query string and a hash string. We’ll talk more about these soon.The

req.headersparameter contains all the headers that were set on this particular request. Of specific interest are authentication headers (which help say who is behind the request and determine if the server should allow the request), and cookie headers. We’ll talk more about this a bit further into the course, when we introduce the associated concepts.

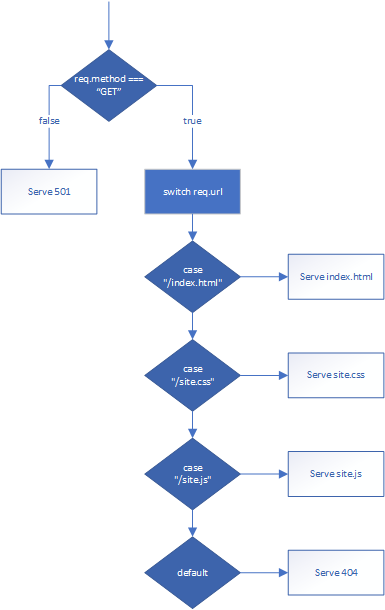

Generally, we use properties in combination to determine what the correct response is. As a programmer, you probably already realize that this decision-making process must involve some sort of control flow structure, like an if statement or switch case statement.

Let’s say we only want to handle "GET" requests for the files index.html, site.css, and site.js. We could write our request handler using both an if else statement and a switch statement:

function handleRequest(req, res) {

if(req.method === "GET") {

switch(req.url) {

case "/index.html":

// TODO: Serve the index page

break;

case "/site.css":

// TODO: Serve the css file

break;

case "/site.js":

// TODO: Serve the js file

break;

default:

// TODO: Serve a 404 Not Found response

}

} else {

// TODO: Serve a 501 Not Implemented response

}

}Notice that at each branching point of our control flow, we serve some kind of response to the requesting web client. Every request should be sent a response - even unsuccessful ones. If we do not, then the browser will timeout, and report a timeout error to the user.

Working with the Response Object

The second half of responding to requests is putting together the response. You will use the http.ServerResponse object to assemble and send the response. This response consists of a status code and message, response headers, and a body which could be text, binary data, or nothing.

There are a number of properties and methods defined in the http.ServerResponse to help with this, including:

- ServerResponse.statusCode can be used to manually set the status code

- ServerResponse.statusMessage can be used to manually set the status message. If the code is set but not the message, the default message for the code is used.

- ServerResponse.setHeader() adds a header with the supplied name and value (the first and second parameters)

- ServerResponse.end() sends the request using the currently set status and headers. Takes an optional parameter which is the response body; if this parameter is supplied, an optional second parameter specifying the encoding can also be used. A final optional callback can be supplied that is called when sending the stream is complete.

Consider the 501 Not Implemented response in our example above. We need to send the 501 status code, but there is no need for a body or additional headers. We could use the req.statusCode property to set the property, and the req.end() method to send it:

// TODO: Serve a 501 Not Implemented response

res.status = 501;

res.end();The sending of a response with a body is a bit more involved. For example, to send the index.html file, we would need to retrieve it from the hard drive and send it as the body of a request. But as the default status code is 200, we don’t need to specify it. However, it is a good idea to specify the Content-Type header with the appropriate mime-type, and then we can use the res.end() method with the file body once we’ve loaded it, i.e.:

// TODO: Serve the index page

fs.readFile('index.html', (err, body) => {

if(err) {

res.status = 500;

res.end();

return;

}

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

res.setHeader("Content-Length", body.length);

res.end(body, "utf8");

});Notice too, that we need to account for the possibility of an error while loading the file index.html. If this happens, we send a 500 Server Error status code indicating that something went wrong, and it happened on our end, not because of a problem in the way the client formatted the request. Notice too that we use a return to prevent executing the rest of our code.

We also supply the length of the response body, which will be the same as the buffer length or the length of a string sent as the body. Binary data for the web is counted in octets (eight bits) which conveniently is also how Node buffers are sized and the size of a JavaScript character.

Chaining writeHead() and end()

The http.ServerResponse object also has a method writeHead() which combines the writing of status code, message, and headers into a single step, and returns the modified object so its end() method can be chained. In this way, you can write the entire sending of a response on a single line. The parameters to response.writeHead() are the status code, an optional status message, and an optional JavaScript object representing the headers, using the keys as the header names and values as values.

Serving the css file using this approach would look like:

// TODO: Serve the site css file

fs.readFile('site.css', (err, body) => {

if(err) return res.writeHead(500).end();

res.writeHead(200, {

"Content-Type": "text/html",

"Content-Length": body.length

}).end(body, "utf8");

});You can use any combination of these approaches to send responses. Some important considerations:

Warning

response.end() has been invoked, it will log an error if it is attempted again.response.writeHead() method actually streams the head to the client. Thus, you cannot run response.setHeader() or set response.statusCode or response.statusMessage after it has been set.response.end() has been invoked will log an error, as you cannot change the response once it’s sent.