Request Revisted

We’ve seen then how the request conveys information useful to selecting the appropriate endpoint with the path, and also the query string. But there is more information available in our request than just those two tidbits. And we have all of that information available to us for determining the correct response to send. With that in mind, let’s revisit the parts of the request in terms of what kinds of information they can convey.

The URL, Revisited

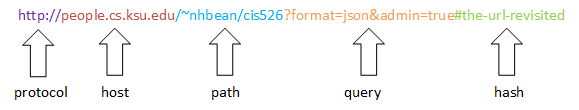

Now that we’re thinking of the URL as a tool for passing information to the server, let’s reexamine its parts:

The protocol is the protocol used for communication, and the host is the domain or IP address of the server. Note that these are not included in Node’s req.url parameter, as these are used to find the right server and talk to it using the right protocol - by the time your Node server is generating the req object, the request has already found your server and is communicating with the protocol.

This is also why when we’ve been parsing req.url with the URL object, we’ve supplied a host and protocol of http://localhost:

var url = new URL(req.url, "http://localhost");This gives the URL object a placeholder for the missing protocol and host, so that it can parse the supplied URL without error. Just keep in mind that by doing so the url.protocol and url.host properties of url equal this “fake” host and protocol.

The path is the path to the virtual resource requested, accessible in our parsed URL as url.pathname. Traditionally, this corresponded to a file path, which is how we used it in our fileserver examples. But as we have seen with Placeholder.com, it can also be used to convey other information - in that case, the size of the image, its background color, and foreground color.

The query or querystring is a list of key-value pairs, preceded by the ?. Traditionally this would be used to modify some aspect of the request, such as requesting a particular data format or portion of a dataset. It is also how forms are submitted with a GET request - the form data is encoded into the query string.

The hash or fragment is preceded by a #, and traditionally indicates an element on the page that the browser should auto-scroll to. This element should have an id attribute that matches the one supplied by the hash. For example, clicking this link: #the-url-revisited will scroll back to the header for this section (note we left the path blank, so the browser assumes we want to stay on this page).

Clearly our URL can clearly convey a lot of data to our server. But that’s not the only information that we can use in deciding how to respond to a request.

Request Method, Revisited

In addition, we also receive the HTTP Method used for the request, i.e. GET, POST, PATCH, PUT, or DELETE. These again map back to the traditional role of a web server as a file server - GET retrieves a resource, POST uploads one, PATCH and PUT modify one, and DELETE removes it. But we can also create, read, update, and destroy virtual resources, i.e. resources generated and stored on the server that are not files. These play an especially important role in RESTful routes, which we’ll discuss soon.

Headers, Revisited

We can also convey additional information for the server to consider as part of the request headers. This is usually used to convey information tangential to the request, like authentication and cookies. We’ll also discuss this a bit further on.