The Update Method

As we mentioned before, the virtual Game.Update(GameTime gameTime) method is a hook for adding your game’s logic. By overriding this method, and adding your own game logic code, you fulfill the update step of the game loop.

This is where you place the simulation code for your game - where the world the game is representing is updated. Here, all your actors (the parts of the game world that move and interact) are updated.

Note the GameTime parameter - it provides us with both the total time the game has been running, and the time that has elapsed between this and the previous step through the game loop (the frame). We can use this in our physics calculations.

Our Simple Example

So in our example, we want the ball to move around the screen, according to its velocity. If you remember your physics, the velocity is the change in position over time, i.e.:

$ \overrightarrow{p'} = \overrightarrow{p} + \overrightarrow{v} * t $We can express this in C# easily:

_ballPosition += _ballVelocity * (float)gameTime.ElapsedGameTime.TotalSeconds;Add this code to the Update() method, just below the // TODO statement. Note that MonoGame provides operator overrides for performing algebraic operations on Vector2 structs, which makes writing expressions involving vectors very much like the mathematical notation. Also, note again that we have to cast the double TotalSeconds into a float as we are loosing some precision in the operation.

Also, note that because we multiply the velocity by the elapsed time, it does not matter what our timestep is - the ball will always move at the same speed. Had we simply added the velocity to the position, a game running with a 60fps timestep would be twice as fast as one running at 30fps.

Info

You may encounter advocates of using a hard-coded fixed time step to avoid calculations with elapsed time. While it is true this approach makes those calculations unnecessary (and thus, makes your code more efficient), you are trading off the ability of your game to adjust to different monitor refresh rates. In cases where your hardware is constant (i.e. the Nintendo Entertainment System), this was an easy choice. But with computer games, I would advocate for always calculating with the elapsed time.

Keeping the Ball on-screen

We need to handle when the ball moves off-screen. We said we wanted to make it bounce off the edges, which is pretty straightforward. First, we need to determine if the ball is moving off-screen. To know when this would happen, we need to know two things:

- The coordinates of the ball

- The coordinates of the edges of the screen

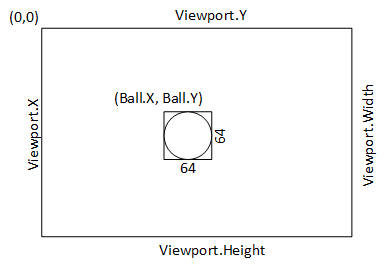

For 1, we have _ballPosition. Let’s assume this is the upper-right corner of the ball image. We’ll also need to factor in the size of the ball. The image linked above is 64 pixels, so I’ll assume that is the size of the ball we’re using. Feel free to change it to match your asset.

For 2, we can use GraphicsDevice.Viewport to get a rectangle defining the screen.

It can be very helpful to draw a diagram of this kind of setup before you try to derive the necessary calculations, i.e.:

To check if the ball is moving off the left of the screen, we could use an if statement:

if(_ballPosition.X < GraphicsDevice.Viewport.X) {

// TODO: Bounce ball

}We could then reverse the direction of the ball by multiplying its velocity in the horizontal plane by $ -1 $:

_ballVelocity.X *= -1;Moving off-screen to the right would be almost identical, so we could actually combine the two into a single if-statement:

// Moving offscreen horizontally

if (_ballPosition.X < GraphicsDevice.Viewport.X || _ballPosition.X > GraphicsDevice.Viewport.Width - 64)

{

_ballVelocity.X *= -1;

}Note that we need to shorten the width by 64 pixels to keep the ball on-screen.

The vertical bounce is almost identical:

// Moving offscreen vertically

if (_ballPosition.Y < GraphicsDevice.Viewport.Y || _ballPosition.Y > GraphicsDevice.Viewport.Height - 64)

{

_ballVelocity.Y *= -1;

}Info

Our bounce here is not quite accurate, as the ball may have moved some pixels off-screen before we reverse the direction. In the worst case, it will go so far off-screen that it might be off-screen next frame as well (a problem exacberated by floating-point rounding error). When this happens the ball gets stuck, bounding back and forth off-screen as we change its direction each frame. But as long as our ball is traveling less than its dimensions each frame, we should be okay.

Other ways to solve this problem include moving the ball back to the position where it would have collided with the edge, or calculating how many pixels it moved off-screen and adding double that distance in the opposite direction.

Now we just need to draw our bouncy ball.