Separating Axis Theorem

But what about sprites with shapes don’t map to a circle or rectangle, such as this spaceship sprite:

We could represent this sprite with a bounding polygon:

The polygon can be represented as a data structure using a collection of vectors from its origin (the same origin we use in rendering the sprite) to the points defining its corners:

/// <summary>

/// A struct representing a convex bounding polygon

/// </summary>

public struct BoundingPolygon

{

/// <summary>

/// The corners of the bounding polygon,

/// in relation to its origin

/// </summary>

public IEnumerable<Vector2> Corners;

/// <summary>

/// The center of the polygon in the game world

/// </summary>

public Vector2 Center;

}But can we detect collisions between arbitrary polygons? Yes we can, but it requires more work (which is why many sprites stick to a rectangular or circular shape).

Separating Axis Theorem

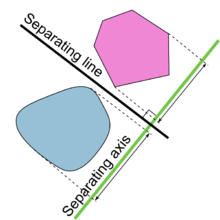

To detect polygon collisions algorithmically, we turn to the separating axis theorem, which states:

For any n-dimensional euclidean space, if we can find a hyperplane separating two closed, compact sets of points we can say there is no intersection between the sets.

As games typically only deal with 2- or 3-dimensional space, we can re-express these general claims in a more specific form:

For 2-dimensional space: If we can find a separating axis between two convex shapes, we can say there is no intersection between them.

For 3-dimensional space: If we can find a separating plane between two convex shapes we can say there is no intersection between them.

This is actually common-sense if you think about it. If you can draw a line between two shapes without touching either one, they do not overlap. In a drawing, this is quite easy to do - but we don’t have the luxury of using our human minds to solve this problem; instead we’ll need to develop an algorithmic process to do the same.

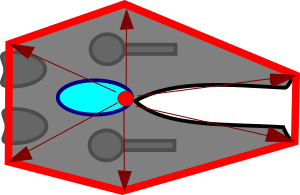

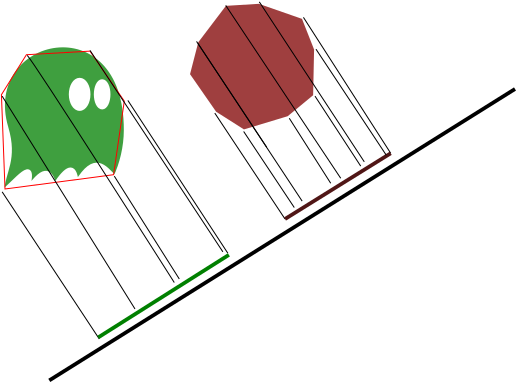

We can accomplish this by projecting the shapes onto an axis and checking for overlap. If we can find one axis where the projections don’t overlap, then we can say that the two shapes don’t collide (you can see this in the figure to the left). This is exactly the process we used with the bounding box collision test earlier - we simply tested the x and y-axis for separation.

Mathematically, we represent this by projecting the shapes onto an axis - think of it as casting a shadow. If we can find an axis where the two shadows don’t overlap, then we know the two don’t intersect:

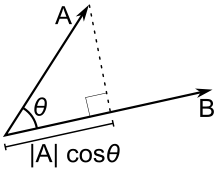

How do we accomplish the projection? Consider each edge (the line between vertices in our polygon) as vector $ A $, and the projection axis as vector $ B $, as in the following figure:

We have two formulae that can be useful for interpreting this figure: the trigonometric definition of cosine (1) and the geometric definition of the cross-product (2).

$$ cos\theta = \frac{|projection\ of\ A\ onto\ B|}{|A|} \tag{1} $$ $$ A \cdot B = |A||B|cos\theta \tag{2} $$

These two equations can be combined to find a formula for projection (3):

$$ projection\ of\ A\ onto\ B = A \cdot \overline{B}, where\ \overline{B} \text{ is a unit vector in the direction of B} \tag{3} $$Thus, given two vectors - one for the axis (which needs to be a unit vector), and one to a corner of our collision polygon, we can project the corner onto the axis. If we do this for all corners, we can find the minimum and maximum projection from the polygon.

A helper method to do this might be:

private static MinMax FindMaxMinProjection(BoundingPolygon poly, Vector2 axis)

{

var projection = Vector2.Dot(poly.Corners[0], axis);

var max = projection;

var min = projection;

for (var i = 1; i < poly.Corners.Length; i++)

{

projection = Vector2.Dot(poly.Corners[i], axis);

max = max > projection ? max : projection;

min = min < projection ? min : projection;

}

return new MinMax(min, max);

}And the class to represent the minimum and maximum bounds:

/// <summary>

/// An object representing minimum and maximum bounds

/// </summary>

private struct MinMax

{

/// <summary>

/// The minimum bound

/// </summary>

public float Min;

/// <summary>

/// The maximum bound

/// </summary>

public float Max;

/// <summary>

/// Constructs a new MinMax pair

/// </summary>

public MinMax(float min, float max)

{

Min = min;

Max = max;

}

}Since we would only be using this class within the collision helper, we could declare it within that class and make it private - one of the few times it makes sense to declare a private class.

If we determine the minimum and maximum projection for both shapes, we can see if they overlap:

If there is no overlap, then we have found a separating axis, and can terminate the search.

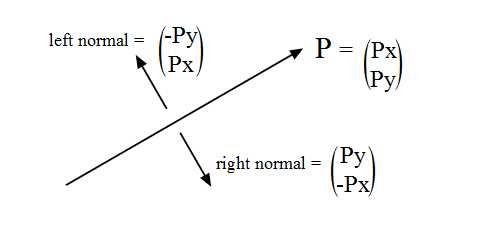

But just which axes should we test? Ideally we’d like a minimal set that promises if a separating axis does exist, it will be found. Geometrically, it can be shown that the bare minimum we need to test is an axis parallel to each edge normal of the polygon - that is, an axis at a right angle to the polygon’s edge. Each edge has two normals, a left and right:

In 2D, an edge normal is a unit vector (of length 1) perpendicular to the edge vector (a vector along the edge). We can calculate it by exchanging the x and y components and negating one of them.

Depending on the order we’ve declared our points (clockwise or anti-clockwise) one of these normals will face out of the polygon, while the other will face in. As long as we’re consistent, either direction will work. We calculate the normals by iterating over our points and creating vectors to represent each edge, and then calculating a perpendicular vector to that edge.

If we were to keep using a struct to represent our collision shape, we could add a field for the normals and implement the normal generation within the constructor:

/// <summary>

/// A struct representing a convex bounding polygon

/// </summary>

public struct BoundingPolygon

{

/// <summary>

/// The corners of the bounding polygon,

/// in relation to its center

/// </summary>

public Vector2[] Corners;

/// <summary>

/// The center of the polygon in the game world

/// </summary>

public Vector2 Center;

/// <summary>

/// The normals of each corner of this bounding polygon

/// </summary>

public Vector2[] Normals;

/// <summary>

/// Constructs a new arbitrary convex bounding polygon

/// </summary>

/// <remarks>

/// In order to be used with Separating Axis Theorem,

/// the bounding polygon MUST be convex.

/// </remarks>

/// <param name="center">The center of the polygon</param>

/// <param name="corners">The corners of the polygon</param>

public BoundingPolygon(Vector2 center, IEnumerable<Vector2> corners)

{

// Store the center and corners

Center = center;

Corners = corners.ToArray();

// Determine the normal vectors for the sides of the shape

// We can use a hashset to avoid duplicating normals

var normals = new HashSet<Vector2>();

// Calculate the first edge by subtracting the first from the last corner

var edge = Corners[Corners.Length - 1] - Corners[0];

// Then determine a perpendicular vector

var perp = new Vector2(edge.Y, -edge.X);

// Then normalize

perp.Normalize();

// Add the normal to the list

normals.Add(perp);

// Repeat for the remaining edges

for (var i = 1; i < Corners.Length; i++)

{

edge = Corners[i] - Corners[i - 1];

perp = new Vector2(edge.Y, -edge.X);

perp.Normalize();

normals.Add(perp);

}

// Store the normals

Normals = normals.ToArray();

} To detect a collision between two BoundingPolygons, we iterate over their combined normals, generating the MinMax of each and testing it for an overlap. Implemented as a method in our CollisionHelper, it would look like something like this:

/// <summary>

/// Detects a collision between two convex polygons

/// </summary>

/// <param name="p1">the first polygon</param>

/// <param name="p2">the second polygon</param>

/// <returns>true when colliding, false otherwise</returns>

public static bool Collides(BoundingPolygon p1, BoundingPolygon p2)

{

// Check the first polygon's normals

foreach(var normal in p1.Normals)

{

// Determine the minimum and maximum projection

// for both polygons

var mm1 = FindMaxMinProjection(p1, normal);

var mm2 = FindMaxMinProjection(p2, normal);

// Test for separation (as soon as we find a separating axis,

// we know there is no possibility of collision, so we can

// exit early)

if (mm1.Max < mm2.Min || mm2.Max < mm1.Min) return false;

}

// Repeat for the second polygon's normals

foreach (var normal in p2.Normals)

{

// Determine the minimum and maximum projection

// for both polygons

var mm1 = FindMaxMinProjection(p1, normal);

var mm2 = FindMaxMinProjection(p2, normal);

// Test for separation (as soon as we find a separating axis,

// we know there is no possibility of collision, so we can

// exit early)

if (mm1.Max < mm2.Min || mm2.Max < mm1.Min) return false;

}

// If we reach this point, no separating axis was found

// and the two polygons are colliding

return true;

}We can also treat our other collision shapes as special cases, handling the projection onto an axis based on their characteristics (i.e. a circle will always have a min and max of projection of center - radius and projection of center + radius).