Elastic Collisions

Now that we’ve looked at movement derived from both linear and angular dynamics, let’s revisit them from the perspective of collisions. If we have two rigid bodies that collide, what should be the outcome? Consider an elastic collision (one in which the two objects “bounce off” one another). From Newtonian mechanics we know that:

- Energy must be conserved

- Momentum must be conserved

Thus, if we consider our two objects in isolation (as a system of two), the total system must have the same energy and momentum after the collision that it had before (Note we are talking about perfectly elastic collisions here - in the real world some energy would be converted to heat and sound).

Momentum is the product of mass and velocity of an object:

$$ \rho = mv\tag{0} $$Since we have two objects, the total momentum in the system is the sum of those:

$$ \rho = m_1v_1 + m_2v_2\tag{1} $$And, due to the law of conservation of momentum,

$$ \rho_{before} = \rho_{after} \tag{2} $$So, substituting equation 1 before and after the collision we find:

$$ m_1u_1 + m_2u_2 = m_1v_1 + m_2v_2\tag{3} $$Where $ u $ is the velocity before a collision, and $ v $ is the velocity after (note that the mass of each object does not change).

And since our objects are both moving, they also have kinetic energy:

$$ E_k = \frac{1}{2}mv^2\tag{4} $$As energy is conserved, the energy before the collision and after must likewise be conserved:

$$ E_{before} = E_{after} \tag{5} $$Substituting equation 4 into 5 yields:

$$ \frac{1}{2}m_0u_0^2 + \frac{1}{2}m_1u_1^2 = \frac{1}{2}m_0v_0^2 + \frac{1}{2}m_1v_1^2 \tag{6} $$Assuming we enter the collision knowing the values of $ u_0, u_1, m_0, and m_1 $, we have two unknowns $ v_0 $ and $ v_1 $ and two equations containing them (equations 3 and 6). Thus, we can solve for $ v_0 $ and $ v_1 $:

$$ v_0 = \frac{m_0 - m_1}{m_0 + m_1}u_0 + \frac{2m_1}{m_0+m_1}u_1 \tag{7} $$ $$ v_1 = \frac{2m_0}{m_0+m_1}u_0 + \frac{m_1 - m_0}{m_0 + m_1}u_1 \tag{8} $$

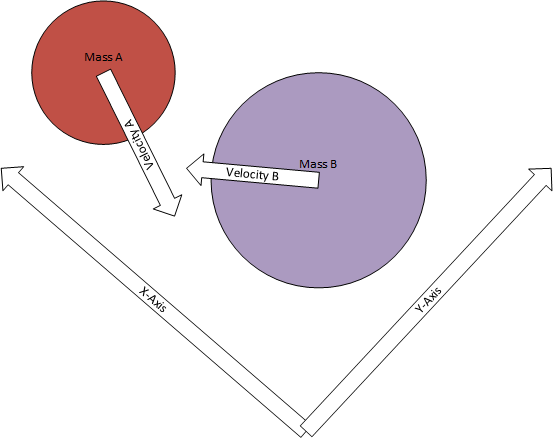

These two equations can give us the new velocities in a single dimension. But we’re primarily interested in two dimensions, and our velocities are expressed as Vector2 objects. However, there is a simple solution; use a coordinate system that aligns with the axis of collision, i.e. for two masses colliding, A and B:

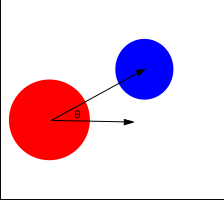

Note how the X-axis in the diagram is aligned with the line between the centers of mass A and B. We can accomplish this in code by calculating the vector between the center of the two bodies, and determining the angle between that vector and the x-Axis:

Remember that the angle between two vectors is related to the dot product:

$$ cos\theta = \frac{ a \cdotp b}{||a||*||b||} \tag {9} $$If both vectors $ a $ and $ b $ are of unit length (normalized), then this simplifies to:

$$ cos\theta = a \cdotp b \tag {10} $$And $ \theta $ can be solved for by:

$$ \theta = cos^{-1}(a \cdotp b) \tag{11} $$Given two rigid bodies A and B, we could then calculate this angle using their centers:

// Determine the line between centers of colliding objects A and B

Vector2 collisionLine = A.Center - B.Center;

// Normalize that line

collisionLine.Normalize();

// Determine the angle between the collision line and the x-axis

float angle = Math.Acos(Vector2.Dot(collisionLine, Vector2.UnitX));Once we have this angle, we can rotate our velocity vectors using it, so that the coordinate system now aligns with that axis:

Vector2 u0 = Vector2.Transform(Matrix.CreateRotationZ(A.Velocity, angle));

Vector2 u1 = Vector2.Transform(Matrix.CreateRotationZ(B.Velocity, angle));We can use these values, along with the masses of the two objects, to calculate the changes in the X-component of the velocity using equations (7) and (8):

float m0 = A.Mass;

float m1 = B.Mass;

Vector2 v0;

v0.X = ((m0 - m1) / (m0 + m1)) * u0.X + ((2 * m1) / (m0 + m1)) * u1.X;

Vector2 v1;

v1.X = ((2 * m0) / (m0 + m1)) * u0.X + ((m1 - m0) / (m0 + m1)) * u1.X;And, because the collision axis and the x-axis are the same, this transfer of velocity only occurs along the x-axis. The y components stay the same!

v0.Y = u0.Y;

v1.Y = u0.Y;Then, we can rotate the velocities back to the original coordinate system and assign the transformed velocities to our bodies:

A.Velocity = Vector2.Transform(v0, Matrix.CreateRotationZ(-angle));

B.Velocity = Vector2.Transform(v1, Matrix.CreateRotationZ(-angle));Some notes on this process:

-

at this point we are not accounting for when the collision has gone some way into the bodies; it is possible that after velocity is transferred one will be “stuck” inside the other. A common approach to avoid this is to move the two apart based on how much overlap there is. A more accurate and costly approach is to calculate the time from the moment of impact until end of frame, move the bodies with the inverse of their original velocities multiplied by this delta t, and then apply the new velocities for the same delta t.

-

this approach only works on two bodies at a time. If you have three or more colliding, the common approach is to solve for each pair in the collision multiple times until they are not colliding. This is not accurate, but gives a reasonable approximation in many cases.