Deeper Dive

Let’s do a bit of a deeper dive into that worked example to explain some of the nuances working with Boolean Logic Expressions, Truth Tables, Venn Diagrams, and the connections between those three. Unfortunately, this is not well explained or covered elsewhere in online resources, but we find that it is really helpful to revisit these concepts here before the end of this module.

Don’t sweat it!

This is a lot of conceptual information to digest at once. However, we don’t expect you to become proficient in this right away! This is just meant to be an introduction to the concept of Boolean Logic and Boolean Algebra, which you’ll become more comfortable with over time as you practice your programming skills and take later classes in Computer Science.

For now, we just want to introduce the topic and give you a chance to try it out in the quiz at the end of this module. If you don’t do well on the quiz, don’t sweat it!

This material is handy if you want to review the concepts or get in some practice, but the best way to learn is to just keep doing examples and practicing as you learn to code.

Key Idea: Truth Table <=> Venn Diagram

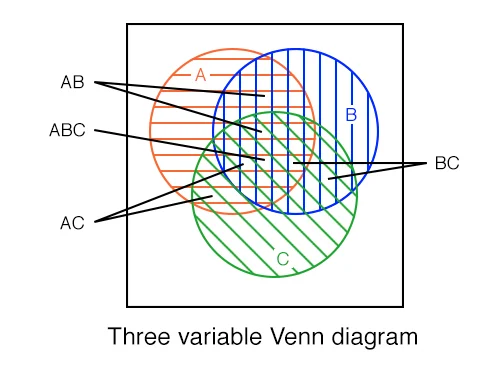

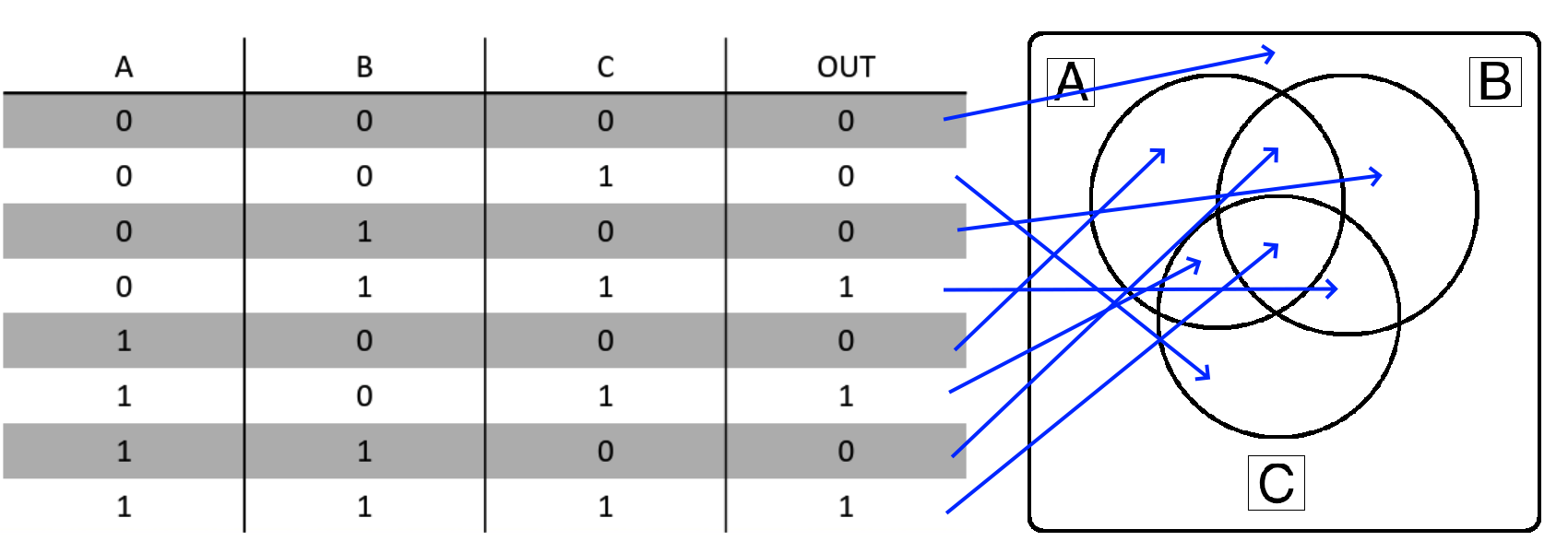

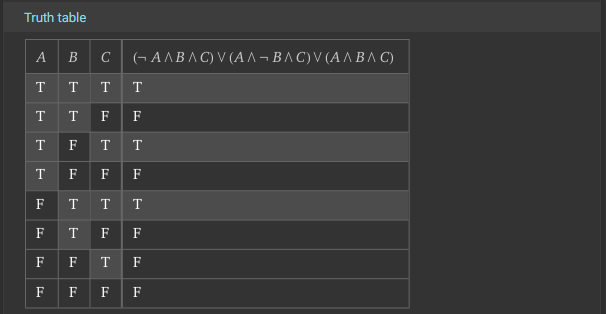

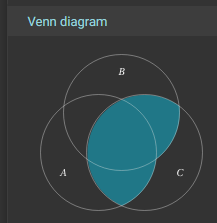

When working with Truth Tables and Venn Diagrams, the key idea to remember is that each line in the Truth Table corresponds to exactly one space in the Venn Diagram.

Each labelled section in the Venn Diagram above corresponds to the variables that are True or 1 in the corresponding Truth Table. We can even draw arrows directly from each line in the Truth Table for Example 1 to the Venn Diagram:

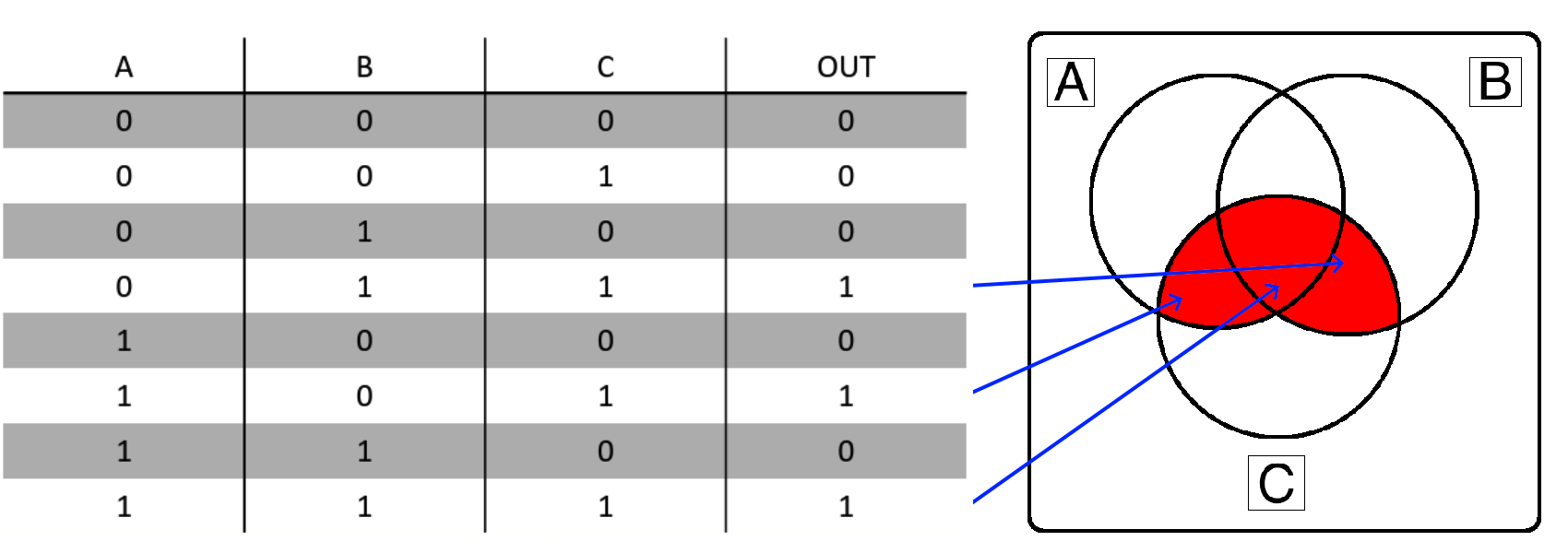

So, if the “OUT” column in the truth table is True or 1, that section of the Venn Diagram becomes shaded and is part of the desired output. Therefore, if you have a Venn Diagram or Truth Table, the conversion between the two is a direct one-to-one connection. Here’s what that looks like for Example 1:

Creating a Boolean Logic Expression

Once we understand either the Truth Table or Venn Diagram for a desired Boolean Logic expression, we can use that information to start building the Boolean Logic expression itself. This can be done in one of three ways:

- We can convert each line in the Truth Table or each shaded section of the Venn Diagram to a single Boolean Logic term that uses all available variables, and then use the rules of Boolean Algebra to reduce the expression to simpler terms. This is generally more comfortable for those who are already well versed in math and algebra, but others may struggle to properly reduce these terms directly on paper.

- We can use a bit of intuition about the Venn Diagram or the real-world scenario we are trying to model to combine adjacent shaded sections of the Venn Diagram together into simple Boolean Logic terms and connect them together. This is what we show in the worked example video, but it does take a bit of experience to become comfortable with this process.

- We can use Karnaugh Maps to directly reduce the statement and produce a Boolean Logic expression. This is typically done in introductory logic circuit design courses in computer engineering, but we rarely teach it anymore in computer science. It is a handy method to know, especially for larger numbers of variables.

So, let’s go through these three methods and see how they relate.

Method 1 - Using Boolean Algebra

Let’s start by directly converting the information in our Truth Table and Venn Diagram to individual Boolean Logic terms. To do this, look at each row in the Venn Diagram where the “OUT” column is 1. Then, for each variable in that row, we either include it in the term directly if it is a True or 1 in the input, or else we include it with a NOT symbol ($\neg$) before the variable if it is a False or 0 in the input. We must include these false variables in our terms, or else we would get different results (i.e. $A \wedge B$ is not the same as $A \wedge B \wedge \neg C$)

So, we would end up with these three terms from our truth table above:

- A is false but B and C are true: $ \neg A \wedge B \wedge C$

- B is false but A and C are true: $ A \wedge \neg B \wedge C$

- A and B and C are true: $ A \wedge B \wedge C$

Finally, our full Boolean Expression using these three terms would combine them using the OR ($\vee$) symbol. This is because the “OUT” column in the Truth Table is True or 1 if any one or more of these terms are True. So, our resulting Boolean Expression at this point would be the following:

$$ (\neg A \wedge B \wedge C) \vee (A \wedge \neg B \wedge C) \vee (A \wedge B \wedge C) $$

At this point, we can stop if we don’t care about reducing the expression to simpler terms. So, once again, there is a direct one-to-one translation from either a Truth Table or Venn Diagram to a Boolean Logic expression that is in this form. In fact, this form is known as the Disjunctive Normal Form of a Boolean Logic expression (though it is not the reduced form). A great way to remember this form is that it is an OR of ANDs (the individual terms are all AND operators, and then the terms are combined using OR operators).

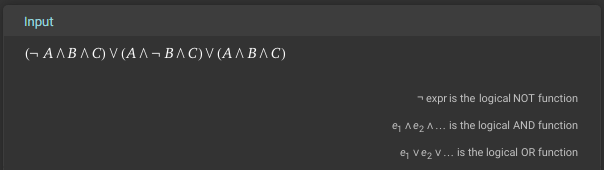

Before we go any further, we can check our work by entering this formula into Wolfram Alpha and checking the Venn Diagram and Truth Table it produces and make sure they match our original setup. While it is possible to enter all of the fancy Boolean Logic symbols into Wolfram Alpha (it does understand them), it is often easiest to just convert them to their English counterparts as shown below:

(NOT A AND B AND C) OR (A AND NOT B AND C) OR (A AND B AND C)You can also click this link to go directly to Wolfram Alpha with this input provided.

First, we can check that our input is parsed correctly since it matches our Boolean Logic expression at the top:

We can also look at the Truth Table and Venn Diagrams further down:

Notice that the Truth Table is ordered a bit differently than what we see above (it is reversed), and the Venn Diagram is rotated a bit, but hopefully it becomes pretty clear that we have a match! So, our translation from the Truth Table to a Boolean Logic Expression is valid!

Method 1A - Reducing Expressions

Once we have a valid Boolean Logic Expression, we can use the laws of Boolean Algebra to reduce it. We cover some of these laws earlier in this chapter, but Wikipedia has a good listing of them as well. We’ll refer to the laws as they are described in Wikipedia as we perform these operations.

First, it is often very helpful to remember that, in many cases, AND ($\wedge$) can be treated similar to multiplication ($\times$), while OR ($\vee$) can be treated like addition ($+$). So, in some fields (such as computer engineering), it is common to rewrite the statement above like this:

$$ (\neg A B C) \vee (A \neg B C) \vee (A B C) $$

This may make some operations more intuitive, especially where we are “factoring out” or “distributing” a term by applying the Distributivity laws. So, we’ll use this modified notation while performing our Boolean Algebra reductions.

Unfortunately, reducing this expression is actually a bit complex, because there is not an obvious starting place. Instead, what we need to do first is duplicate a term by applying the inverse of the Idempotence of $\vee$ law. This law states that $ x \vee x = x $, so we can invert it by replacing any single term $x$ with two instances of the term that are connected with the OR ($\vee$) operator. We’ll do this to the last term in the expression for now:

$$ (\neg A B C) \vee (A \neg B C) \vee (A B C) \vee (A B C) $$

Next, we want to group some similar terms together to make later operations a bit more obvious. So, we’ll apply the Commutativity of $\vee$ law to rearrange the terms, and also use the Associativity of $\vee$ law to group some terms together:

$$ \Big( (\neg A B C) \vee (A B C) \Big) \vee \Big( (A \neg B C)\vee (A B C) \Big) $$

Now we can start to simplify things a bit. In both groups of terms, we notice that they each share the variable $C$, so we can apply the inverse of the Distributivity of $\wedge$ over $\vee$ law to “factor out” that term. Notice that this is very similar to how we can apply a similar law in ordinary algebra:

$$ \Big( C \wedge \big((\neg A B) \vee (A B) \big) \Big) \vee \Big( C \wedge \big( (A \neg B)\vee (A B) \big) \Big) $$

After that, we’ll see that the first pair of remaining terms shares the variable B, while the second pair of terms shares the variable A. So, we can once again apply the Distributivity of $\wedge$ over $\vee$ law to “factor out” those shared terms in each pair:

$$ \Big( C \wedge \big(B \wedge (\neg A \vee A) \big) \Big) \vee \Big( C \wedge \big(A \wedge (\neg B \vee B) \big) \Big) $$

Now we can start to remove some terms. The Complementation 2 law in Wikipedia states that $x \vee \neg x = 1$, which means that we can replace a term and the inverse of that term connected with an OR ($\vee$) operator with the value True or 1. We’ll do this for both $A$ and $B$ terms:

$$ \Big( C \wedge \big(B \wedge 1 \big) \Big) \vee \Big( C \wedge \big(A \wedge 1 \big) \Big) $$

Next, we can use the Identity for $\wedge$ law, which states that $x \wedge 1 = x$, to effectively remove those True or 1 terms from the statement. Again, remember that in regular algebra, we would know that the term $1A$ would be equivalent to just $A$, so if we rewrite $A \wedge 1$ as just $1A$ and then just $A$, it feels very logical!

$$ ( C B ) \vee ( C A ) $$

Finally, if desired, we can apply the Distributivity of $\wedge$ over $\vee$ law one more time to “factor out” the $C$ variable again:

$$ C \wedge (B \vee A) $$

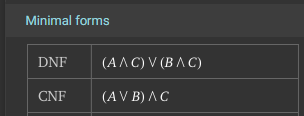

There we go! Both of those reductions are valid minimal forms of the Boolean Logic Expression. Once again, we can go back to Wolfram Alpha to check our work:

In that screenshot, we can see both the minimal Disjunctive Normal Form (DNF) as well as the minimal Conjunctive Normal Form (CNF) for the expression.

Method 2 - Using Intuition

Another great way to convert a Truth Table or Venn Diagram into a Boolean Logic Expression is to use a bit of intuition. The video earlier in this chapter showed one way to do this suing the Venn Diagram, but let’s use another method - using a concrete example!

For this example, let’s assume that we have been given the following rules:

- If Mom says yes and it is sunny outside, we can go swimming even if we don’t have friends over.

- If Mom says yes and we have friends over, we can go swimming even if it isn’t sunny outside.

- If Mom says yes, we can go swimming if it is sunny outside and we have friends over.

We can build a Truth Table using these rules as shown below:

| Friends Over (A) | Sunny Outside (B) | Mom Says Yes (C) | Go Swimming |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Ahh! Notice that this Truth Table is identical to the Truth Table given in Example 1 shown above! We have created a set of rules that immediately generate the same Boolean Logic Expression that matches our example. It may take a little bit of thinking, and we have to state the rules very clearly, but generally we can always create a set of rules that clearly describe any Truth Table. In practice, we often are starting with a set of rules like this (in our specifications document), and we are trying to build a Boolean Logic Expression that we can use in our code as we implement those specifications in our program.

Now, let’s use a bit of intuition about those rules above to generate a Boolean Logic Expression. If we really want to go swimming, we’ll quickly realize that there are two main things that we need to have:

- Mom has to say yes (C), and

- It must either be sunny outside (B) or we have to have friends over (A) (or both)

Look closely at those rules! Just by talking through the scenario, we have created a Boolean Logic expression. Let’s rewrite it:

Mom must say yes

AND(it must be sunny outsideORwe have to have friends over)

If we replace each part with the corresponding variable, we can find the corresponding statement:

$$ C \wedge (B \vee A) $$

A similar way to state the rules might be:

- Mom has to say yes and it has to be sunny, or

- Mom has to say yes, and we have to have friends over

Once again, we can rewrite that a bit to make the Boolean Logic operators more obvious:

(Mom must say yes

ANDit must be sunny outside)OR(Mom must say yesANDwe have to have friends over)

Finally, we can replace those parts with variables to get the corresponding statement:

$$ (C \vee B) \wedge (C \vee A) $$

So, as we can see, applying a bit of intuition to a real-world example that creates the same situation can make it pretty easy to work out a simple Boolean Logic Expression from a Truth Table or Venn Diagram.

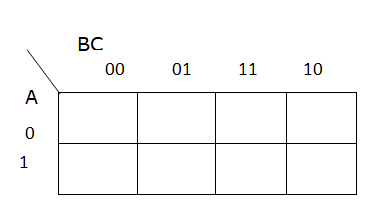

Method 3 - Karnaugh Maps

The third method would be to use a Karnaugh Map. We won’t go into this method in too much depth, but we’ll briefly show how it works. There are some great online resources to learn more about applying Karnaugh Maps in this context.

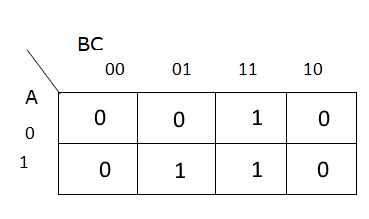

First, we’ll start with a blank 3 variable Karnaugh map. A Karnaugh Map is essentially a different way to structure a truth table by placing similar entries next to each other in a particular way:

Then, we’ll input the desired outputs from the Truth Table in each square of the Karnaugh Map:

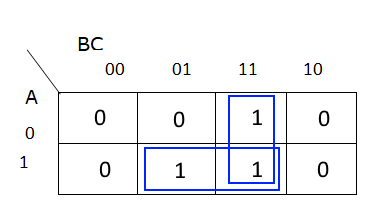

Now, we’ll group connected terms. These groups can be either rectangular or square boxes. So, for this Karnaugh Map, there are two groups:

Finally, for each group, we identify the variables that don’t change within that group, and those become our terms. So, for the group in the bottom row, we see that both $A$ and $C$ are the same, but $B$ changes. So, one term we find is $AC$. For the group in the third column, we see that $B$ and $C$ are the same, but $A$ changes, so our other term is $BC$. Then, we combine those two terms together using the OR ($\vee$) operator to get this statement:

$$ (AC) \vee (BC) $$

There we go! That is once again one of our minimal Boolean Logic expressions found earlier.

Method 3A - Venn Diagrams as Karnaugh Maps

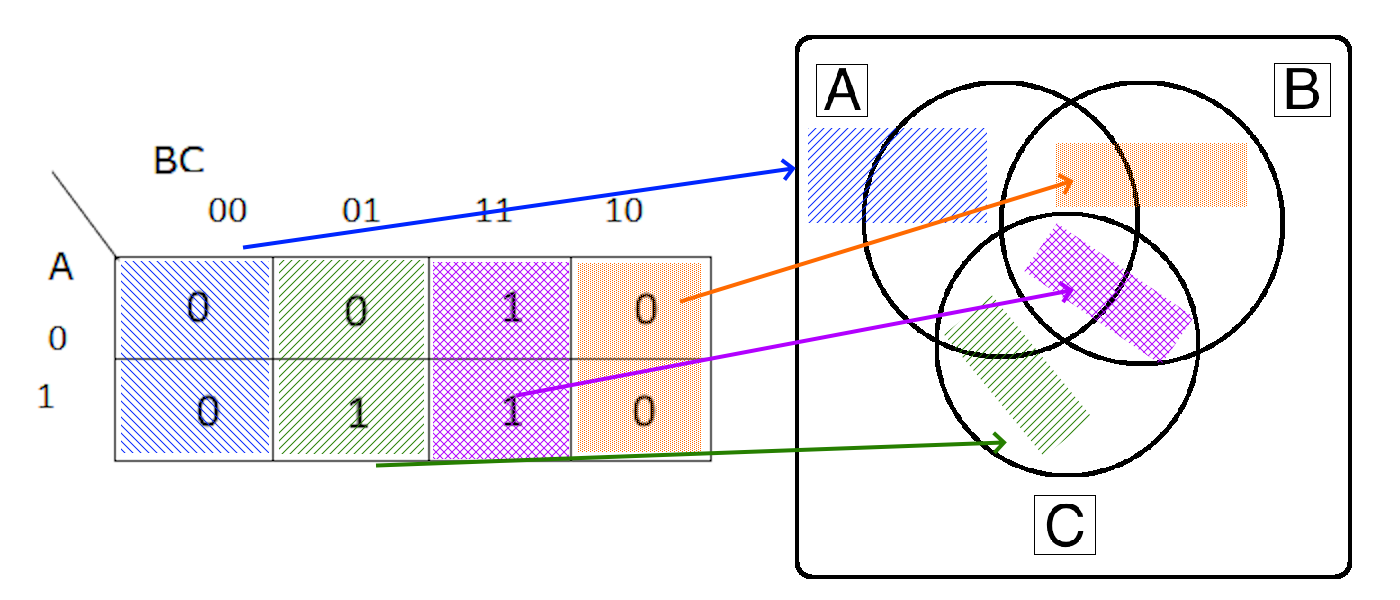

Once clever things that we might notice is that there is also a one-to-one equivalence between Karnaugh Maps and Venn Diagrams. We know this since there is already a one-to-one equivalence between both of those and the original Truth Tables, so it is an easy assumption to make.

So, we can quickly see the arrangement of items in a Karnaugh Map and how they match up to our Venn Diagrams as shown below:

Notice that the the Venn Diagram has a very similar layout to the Karnaugh Map. This is because both of them are structured in a way for similar entries to be near each other. In fact, each time you cross over a line in a Venn Diagram, only a single variable changes value. The same works for a Karnaugh Map.

So, with a little intuition and an understanding how Karnaugh Maps work, we can perform a similar analysis directly on the Venn Diagram itself.

Connection to Programming

Why does all of this matter? Well, when we are trying to convert a real-world situation to code, it is often helpful (but not necessary) to be able to reduce our Boolean Logic expressions to simpler terms.

Let’s go back to the concrete example shown above. If we wanted to write a Python program for this, there are a few ways we could build it.

First, here’s what it would look like if we just directly encoded the rules as written:

# bool() returns False if the input is the number 0, otherwise True

# so we have to convert the string to an int first

sunny = bool(int(input("Is it sunny outside? (1 = yes, 0 = no)")))

friends = bool(int(input("Do you have friends over? (1 = yes, 0 = no)")))

mom = bool(int(input("Did Mom say yes? (1 = yes, 0 = no)")))

"""

Rules:

* If Mom says yes and it is sunny outside, we can go swimming even if we don't have friends over.

* If Mom says yes and we have friends over, we can go swimming even if it isn't sunny outside.

* If Mom says yes, we can go swimming if it is sunny outside and we have friends over.

"""

if (mom and sunny and not friends)

or (mom and friends and not sunny)

or (mom and friends and sunny):

print("We can go swimming")

else:

print("We cannot go swimming")We could also use if-else statements instead of the or operator to achieve a similar effect:

if mom and sunny and not friends:

print("We can go swimming")

else if mom and friends and not sunny:

print("We can go swimming")

else if mom and friends and sunny:

print("We can go swimming")

else:

print("We cannot go swimming")However, in both cases, these programs are more complex than they actually need to be, and it may make things more difficult to debug down the road. So, with a little intuition and the ability to reduce Boolean Logic expressions effectively (and correctly), we can simplify this code quite a bit:

if mom and (sunny or friends):

print("We can go swimming")

else:

print("We cannot go swimming")Hopefully you can see the value in that much simpler program, both in terms of how easy it is to understand and debug, but possibly how much more efficient it is overall since it has fewer comparison to make.

Image Source: https://www.allaboutcircuits.com/textbook/digital/chpt-8/boolean-relationships-on-venn-diagrams/ ↩︎

Image Source: https://www.wolframalpha.com/input?i=%28NOT+A+AND+B+AND+C%29+OR+%28A+AND+NOT+B+AND+C%29+OR+%28A+AND+B+AND+C%29 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Image source: https://www.learnelectronicswithme.com/2021/09/karnaugh-map-and-steps-to-solve.html ↩︎