Resources

One important concept to understand when writing if statements and if-else statements is the control flow of the program. Before we learned about conditional statements, our programs had a linear control flow - there was exactly one pathway through the program, no matter what. Each time we ran the program, the same code would be executed each time in the same order. However, with the introduction of conditional statements, this is no longer the case.

Because of this, testing our programs becomes much more complicated. We cannot simply test it once or twice, but instead we should plan on testing our programs multiple times to make sure they work exactly the way we want. So, let’s go through some of the various ways we can test our programs that include conditional statements.

Simple Example

First, let’s consider this example program:

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if x + y > 10:

print("Branch 1")

else:

print("Branch 2")

if x - y > 10:

print("Branch 3")

else:

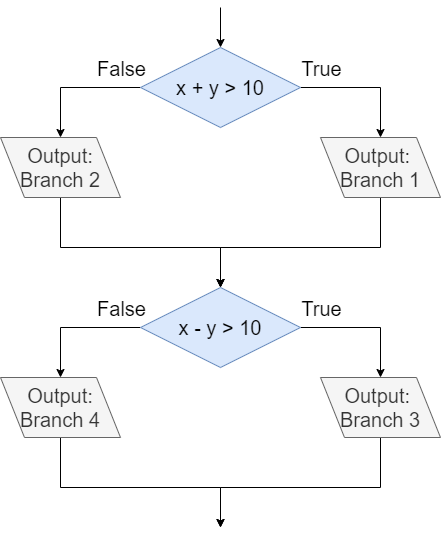

print("Branch 4")We can represent the two if-else statements in this program in the following flowchart as well:

Branch Coverage

First, let’s consider how we can achieve branch coverage by executing all of the branches in this program. This means that we should test the program using different sets of inputs that will run different branches in the code. Our goal is to execute the code in each branch at least once. In this example, we see that there are four branches, helpfully labeled with the numbers one through four in the print() statements included in each branch.

So, let’s start with a simple set of inputs, which will store

$ 6 $ in both x and y. Which branches will be executed in this case? Before reading ahead, see if you can work through the code above and determine which branches are executed?

In the first if-else statement, we’ll see the x + y is equal to

$ 12 $, which is greater than

$ 10 $, making that Boolean statement True. So, we’ll execute the code in branch 1 this time through. When we reach the second if-else statement, we’ll compute the value of x - y to be

$ 0 $, which is less than

$ 10 $. In this case, that makes the Boolean statement False, so we’ll execute branch 4. Therefore, by providing the inputs 6 and 6, we’ve executed the code in branches 1 and 4.

So, can we think of a second set of inputs that will execute the code in branches 2 and 3? That can be a bit tricky - we want to come up with a set of numbers that add to a value less than

$ 10 $, but with a difference that is greater than

$ 10 $. However, we can easily do this using negative numbers! So, let’s assume that the user inputs

$ 6 $ for x and

$ -6 $ for y. When we reach the first if-else statement, we can compute the result of x + y, which is

$ 0 $. That is less than

$ 10 $, so the Boolean statement is False and we’ll execute the code in branch 2. So far, so good!

Next, we’ll reach the second if-else statement. Here, we’ll compute the result of x - y. This time, we know that

$ 6 - -6 $ is actually

$ 12 $, which is greater than

$ 10 $. So, since that Boolean expression is True, we’ll run the code in branch 3. That’s exactly what we wanted!

Therefore, if we want to test this program and try to execute all the branches, we only have to provide two pairs of inputs:

- $ 6 $ and $ 6 $

- $ 6 $ and $ -6 $

However, that’s only one way we can test our program. There are many other methods we can follow!

Path Coverage

A more thorough way to test our programs is to achieve path coverage. In this method, our goal is to execute all possible paths through the program. This means that we want to execute every possible ordering of branches! So, since our program has 4 branches in two different if-else statements, the possible orderings of branches are listed below:

- Branch 1 -> Branch 3

- Branch 1 -> Branch 4

- Branch 2 -> Branch 3

- Branch 2 -> Branch 4

As we can see, there are twice as many paths as there are branches in this case! We’ve already covered ordering 2 and 3 from this list, so let’s see if we can find inputs that will cover the other two orderings.

First, we want to find a set of inputs that will execute branch 1 followed by branch 3. So, we’ll need two numbers that add to a value greater than 10, but their difference is also greater than 10. So, let’s try the value

$ 12 $ for x and

$ 0 $ for y. In that case, their sum is greater than

$ 10 $, so we’ll execute branch 1 in the first if-else statement. When we reach the second if-else statement, we can evaluate x - y and find that it is also

$ 12 $, which is greater than

$ 10 $ and we’ll execute branch 3. So, we’ve covered the first ordering!

The last ordering can be done in a similar way - we need a pair of inputs with a sum less than

$ 10 $ and also a difference less than

$ 10 $. A simple answer would be to input

$ 4 $ for both x and y. In this case, their sum is

$ 8 $ and their difference is

$ 0 $, so we’ll end up executing branch 2 of the first if-else statement, and branch 4 of the second if-else statement. So, that covers the last ordering.

As we can see, path coverage will also include branch coverage, but it is a bit more difficult to achieve. If we want to cover all possible paths, we should test our program with these 4 sets of inputs now:

- $ 6 $ and $ 6 $

- $ 6 $ and $ -6 $

- $ 12 $ and $ 0 $

- $ 4 $ and $ 4 $

There’s still one more way we can test our program, so let’s try that out as well.

Edge Cases

Finally, we should also use a set of inputs that test the “edges” of the Boolean expressions used in each if-else statement. An edge is a value that is usually the smallest or largest value before the Boolean expression’s output would change. So, an edge case is simply a set of input values that are specifically created to be edges for the Boolean expressions in our code.

For example, let’s look at the first Boolean logic statement, x + y > 10. If we are simply considering whole numbers, then the possible edge cases for this Boolean expression are when the sum of x + y is exactly

$ 10 $ and

$ 11 $. When it is

$ 10 $ or below, the result of the Boolean expression is False, but when the result is

$ 11 $ or higher, then the Boolean expression is true. So,

$ 10 $ and

$ 11 $ represent the edge between True values and False values. The same applies to the Boolean expression in the second if-else statement.

So, to truly test the edge cases in this example, we should come up with a set of values with the sum and difference of exactly

$ 10 $ and exactly

$ 11 $. For the first one, a very easy solution would be to set x to

$ 10 $ and y to

$ 0 $. In this case, both the sum and the difference is

$ 10 $, so we’re on the False side of the edge. Our program will correctly execute branches 2 and 4.

For the other edge, we can use a similar set of inputs where x is

$ 11 $ and y is still

$ 0 $. In this case, both the sum and difference is

$ 11 $, so each Boolean expression will evaluate to True and we’ll execute branches 1 and 3.

Why is this important? To understand that, we must think a bit about what was intended by this program. What if the program should execute branches 1 and 3 if the value is greater than or equal to

$ 10 $? In that case, both of our chosen edge cases should execute branches 1 and 3, but instead we saw that the edge case

$ 10 $ executed branches 2 and 4 instead. This is a simple logic error that happens all the time in programming - we simply forgot to use the greater than or equal to symbol >= instead of the simple greater than symbol > in our code. So, a minor typo like that can change the entire execution of our program, and we wouldn’t have noticed it in any of our previous tests. This is why it is important to test the edge cases along with other inputs.

In fact, it would probably be a good idea to add a third edge case, where the sum and difference equal

$ 9 $, just to be safe. That way, we can clearly see the difference between True and False values in this program.

So, the final set of values we may want to test this program with are listed below:

- $ 6 $ and $ 6 $ (branch coverage 1 and 4)

- $ 6 $ and $ -6 $ (branch coverage 2 and 3)

- $ 12 $ and $ 0 $ (path coverage 1 and 3)

- $ 4 $ and $ 4 $ (path coverage 2 and 4)

- $ 9 $ and $ 0 $ (edge case 2 and 4)

- $ 10 $ and $ 0 $ (edge case 2 and 4)

- $ 11 $ and $ 0 $ (edge case 1 and 3)

As we can see, even a simple program with just a few lines of code can require substantial testing to really be sure it works correctly! This doesn’t even include other types of testing, where we make sure it works properly with invalid input values, decimal numbers, and other situations. That type of testing is really outside of the scope of this lab, but we’ll learn more about some of those topics later in this course.

Complex Example

Let’s go through one more example to get some more practice with creating test inputs for conditional statements. For this example, let’s consider the following program in Python:

a = int(input("Enter a number: "))

b = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if a // b >= 5:

# Branch 1

print(f"{b} goes into {a} at least 5 times")

else:

# Branch 2

print(f"{a} is less than 5 times {b}")

if a % b == 0:

# Branch 3

print(f"{b} evenly divides {a}")

else:

# Branch 4

print(f"{a} / {b} has a remainder")This program is a bit trickier to evaluate. First, it accepts two numbers as input. Then, it will check to see if the first number is at least 5 times the second number. It will print an appropriate message in either case. Then, it will check to see if the first number is evenly divided by the second number, and once again it will print a message in either case.

Branch Coverage

To achieve branch coverage, we need to come up with a set of inputs that will cause each print statement to be executed. Thankfully, the branches are numbered using comments in the Python code, so it is easy to keep track of them.

Let’s start with an easy input - we’ll set a to

$ 25 $ and b to

$ 5 $. This means that a // b is equal to

$ 5 $, so we’ll go into branch 1 in the first if statement. The second if statement will go into branch 3, since a % b is exactly

$ 0 $ because

$ 5 $ stored in b will evenly divide the

$ 25 $ stored in a without any remainder. So, we’ve covered branches 1 and 3 with this input.

For another input, we can choose

$ 21 $ for a and

$ 5 $ for b. In the first if statement, we’ll see that a // b is now

$ 4 $, so we’ll go into branch 2 instead. Likewise, in the second if statement we’ll execute branch 4, since a % b is equal to

$ 1 $ with these inputs. That means we’ve covered branches 2 and 4 with these inputs.

Therefore, we can achieve branch coverage with just two inputs:

- $ 25 $ and $ 5 $

- $ 21 $ and $ 5 $

Path Coverage

Recall that there are four paths through a program that consists of two if statements in a row:

- Branch 1 -> Branch 3

- Branch 1 -> Branch 4

- Branch 2 -> Branch 3

- Branch 2 -> Branch 4

We’ve already covered the first and last of these paths, so we must simply find inputs for the other two.

One input we can try is

$ 31 $ and

$ 5 $. In the first if statement, we’ll go to branch 1 since a // b will be

$ 6 $ this time. However, when we get to the second if statement, we’ll find that there is a remainder of

$ 1 $ after computing a % b, so we’ll go to branch 4 instead. This covers the second path.

The third path can be covered by inputs

$ 20 $ and

$ 5 $. In the first if statement, we’ll go to branch 2 because a // b is now

$ 4 $, but we’ll end up in branch 3 in the second if statement since a % b is exactly 0.

Therefore, we can achieve path coverage with these four inputs:

- $ 25 $ and $ 5 $

- $ 21 $ and $ 5 $

- $ 31 $ and $ 5 $

- $ 20 $ and $ 5 $

Edge Cases

What about edge cases? For the first if statement, we see the statement a // b >= 5, so that clues us into the fact that we’ll probably want to try values that result in the numbers

$ 4 $,

$ 5 $, and

$ 6 $ for this statement. Thankfully, if we look at the inputs we’ve already tried, we can see that this is already covered! By being a bit deliberate with the inputs we’ve been choosing, we can not only achieve branch and path coverage, but we can also choose values that test the edge cases for various Boolean expressions as well.

Likewise, the Boolean statement in the second if statement is a % b == 0, so we’ll want to try situations where a % b is exactly

$ 0 $, and when it is some other value. Once again, we’ve already covered both of these instances in our sample inputs!

So, with a bit of thinking ahead, we can come up with a set of just 4 inputs that not only achieve full path and branch coverage, but also properly test the various edge cases that are present in the program!