Blocks & Scope

Resources

Now that we’ve seen how we can chain and nest multiple conditional statements in our code, we need to address a very important concept: variable scope.

In programming, variable scope refers to the locations in code where variables can be accessed. Contrary to what we may think based on our experience, when we declare a variable in our code, it may not always be available everywhere. Instead, we need to learn the rules that determine where variables are available and why.

Many Languages: Block Scope

The example below demonstrates block scope, which is NOT how Python handles scope. We are using Python code so the example is understandable, but Python handles scope differently. See the next section for how Python actually handles scope.

First, let’s talk about the most common type of variable scope, which is block scope. This type of variable scope is used in many programming languages, such as Java, C#, C/C++, and more. In block scope, variables are only available within the blocks where they are declared, including any other blocks nested within that block. Also, variables can only be accessed by code executed after the variable is initially declared or given a value.

So, what is a block? Effectively, each function and conditional statement introduces a new block in the program. In languages such as Java and C/C++, blocks are typically surrounded by curly braces {}. In Python, blocks are indicated by the level of indentation.

For example, consider the following Python code:

# Global block

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if x > 5:

# block A

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if y > 10:

# block B

z = 10

else:

# block C

z = 5

elif x < 0:

# block D

a = -5

else:

# block E

b = 0

print("?")This program contains six different blocks of code:

- The

Globalblock, which is all of the code at the top level of the file - Block

A, which is all of the code inside of theTruebranch of the outermost conditional statement. - Block

B, theTruebranch of the inner conditional statement - Block

C, theFalsebranch of the inner conditional statement - Block

D, theTruebranch of the firstelifclause of the outer conditional statement - Block

E, theFalsebranch of the outermost conditional statement

Inside of each of those blocks, we see various variables that are declared. For example, the variable x is declared in the Global block. So, with block scope, this means that the variable x is accessible anywhere inside of that block, including any blocks nested within it.

Below is a list of all of the variables in this program, annotated with the blocks where that variable is accessible in block scope:

x- blocksGlobal,A,B,C,D,Ey- blocksA,B,Cz- blocksBandCmore on this latera- blockDb- blockE

One thing that is unique about this example is the variable z, which is declared in both block B and block C. What does this mean when we are dealing with block scope? Basically, those variables named z are actually two different variables! Since they cannot be accessed outside of the block that they are declared in, they should really be considered as completely separate entities, even though they are given the same name. This is one of the trickiest concepts when dealing with scope!

So, if this program is using block scope, what variables can be printed at the very end of the program, where the question mark ? is found in a print() statement? In this case, only the variable x exists in the Global block’s scope, so it is the only variable that we can print at the end of the program.

If we want to print the other variables, we must declare them in the appropriate scope. So, we can update our code as shown here to do that:

# Global block

# variable declarations in Global block

y = 0

z = 0

a = 0

b = 0

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if x > 5:

# block A

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if y > 10:

# block B

z = 10

else:

# block C

z = 5

elif x < 0:

# block D

a = -5

else:

# block E

b = 0

print("?")With this change, we can now access all of the variables in the Global scope, so any one of them could be printed at the end of the program. This also has the side effect of making the variable z in both blocks B and C the same variable, since it is now declared at a higher scope.

Python: Function Scope

Python, however, uses a different type of variable scope known as function scope. In function scope, variables that are declared anywhere in a function are accessible everywhere in that function as soon as they’ve been declared or given a value. In Python, the Global scope is treated the same as a function’s scope, so variables declared in the Global scope in Python are accessible everywhere. So, once we see a variable in the code while we’re executing within a function or in the Global scope, we can access that variable anywhere within the same scope.

We haven’t introduced functions in Python quite yet, but it is important to go ahead and use the correct terminology here. For now, you can think of everything as being part of the “Global” function in Python. We’ll revisit this concept later when we introduce functions.

Let’s go back to the previous example, and look at that in terms of function scope

# Global block

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if x > 5:

# block A

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

if y > 10:

# block B

z = 10

else:

# block C

z = 5

elif x < 0:

# block D

a = -5

else:

# block E

b = 0

print("?")Using function scope, any of the variables x, y, z, a or b could be placed in the print() statement at the end of the code, and the program could work. However, there is one major caveat that we must keep in mind: we can only print the variable if it has been given a value in the program!

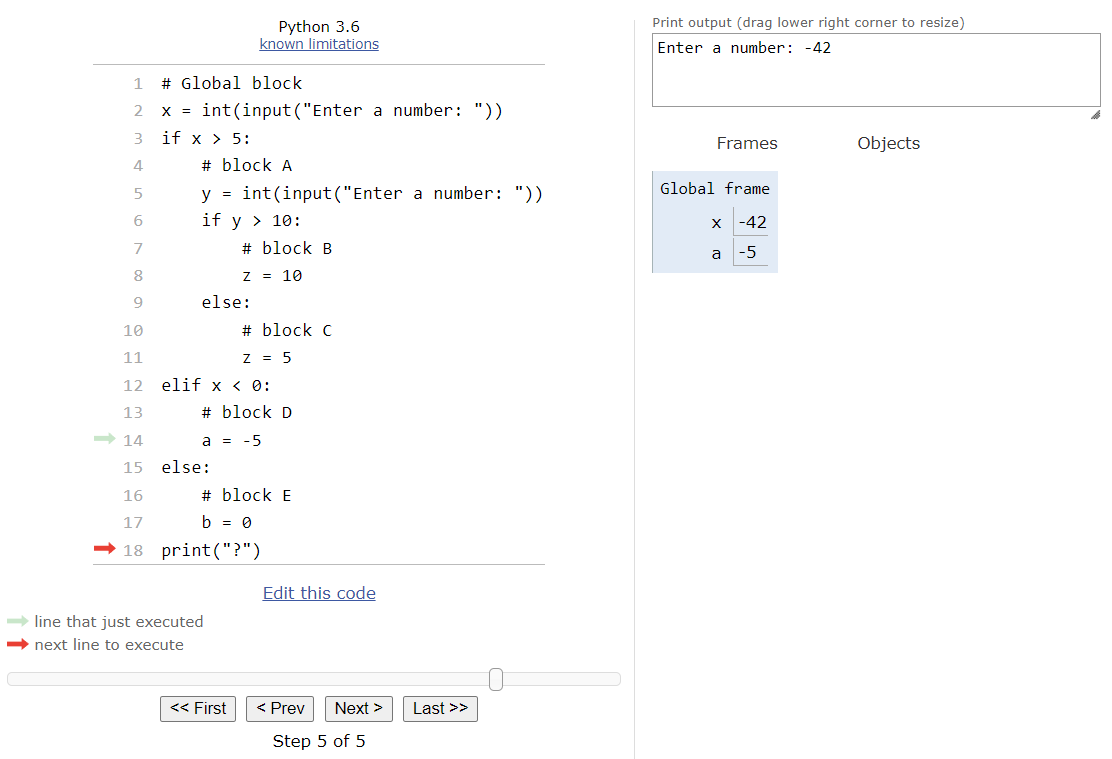

For example, if the user inputs a negative value for x, then the variables y, z, and b are never given a value! We can confirm this by running the program in Python Tutor. As we see here, at the end of the program, only the variables x and a are shown in the list of variables within the Global frame in Python Tutor on the right:

Because of this, we have to be careful when we write our programs in Python using function scope. It is very easy to find ourselves in situations where our program will work most of the time, since it usually executes the correct blocks of code to populate the variables we need, but there may be situations where that isn’t guaranteed.

This is where testing techniques such as path coverage are so important. If we have a set of inputs that achieve path coverage, and we are able to show that the variables we need are available at the end of the program in each of those paths, then we know that we can use them.

Alternatively, we can build our programs in Python as if Python used block scope instead of function scope. By assuming that variables are only available in the blocks where they are given a value, we can always ensure that we won’t reach a situation where we are trying to access a variable that isn’t available. For novice programmers, this is often the simplest option.

Dealing with scope is a tricky part of learning to program. Thankfully, in Python, as well as many other languages, we can easily use tools such as Python Tutor and good testing techniques to make sure our programs are well written and won’t run into any errors related to variable scope.