Nested For Loops

YouTube VideoResources

For loops can also be nested, just like while loops. In fact, nesting for loops is often much simpler than nesting while loops, since it is very easy to predict exactly how many times a for loop will iterate, and also because it is generally easier to determine if a for loop will properly terminate instead of a while loop.

A great way to explore using nested for loops is by printing ASCII Art shapes. For example, consider the following Python program that contains nested for loops:

for i in range(3):

for j in range(5):

print("* ", end="")

print("")Just by looking at the code, can you predict what shape it will print? We can check the result by running the program on the terminal directly. If we do so, we should receive this output:

* * * * *

* * * * *

* * * * * It printed a rectangle that is $ 3 $ rows tall (the outer for loop) and $ 5 $ columns wide (the inner for loop). If we look back at our code, this hopefully becomes very clear. This is a very typical structure for nested for loops - the innermost loop will handle printing one line of data, and then the outer for loop is used to determine the number of lines that will be printed.

The process for dealing with nested for loops is nearly identical to nested while loops. So, we won’t go through a full example using Python Tutor. However, feel free to run any of the examples in this lab in Python Tutor yourself and make sure you clearly understand how it works and can easily predict the output based on a few changes.

Example 1

Let’s look at a few more examples of nested for loops and see if we can predict the shape that is created when we run the code.

for i in range(5):

for j in range(i + 1):

print("* ", end="")

print("")This time, we’ve updated the inner for loop to use range(i + 1), so each time that inner loop is reached, the range will be different based on the current value of i from the outer loop. So, we can assume that each line of text will be a different size. See if you can figure out what shape this will print!

When we run the code, we’ll get this output:

*

* *

* * *

* * * *

* * * * * We see a triangle that is

$ 5 $ lines tall and

$ 5 $ columns wide. If we look at the code, we know that we’ll have 5 rows of output based on the range(5) used in the outer loop. Then, in the inner loop, we can see that the first time through we’ll only have a single item, since i is

$ 0 $ and the range used is range(i + 1).

The next iteration of the outer loop will have

$ 1 $ stored in i, so we’ll end up repeating the inner loop

$ 2 $, or i + 1, times. We’ll repeat that process until the final line, which will have

$ 5 $ characters in it to complete the triangle.

From here, we can quickly modify the program to change the structure of the triangle. For example, to flip the triangle and make it point downward, we can change the range in the inner loop to range(i, 5) instead!

Example 2

What if we want to flip the triangle along the vertical axis, so that the long side runs from the top-right to the bottom-left? How can we change our nested loops to achieve that outcome?

In that case, we’ll not only have to print the correct number of asterisks, but we’ll also need to print the correct number of spaces on each line, before the asterisks. One possible way to achieve this is shown in this code:

for i in range(5):

for j in range(4 - i):

print(" ", end="")

for j in range(i + 1):

print("* ", end="")

print("")Here, we have two for loops nested inside of our outer loop. The first loop creates a range using the expression 4 - i, and the second loop uses the expression i + i. So, when i is equal to

$ 0 $ during the first iteration of the outer loop, the first inner loop will be executed

$ 4 $ times, and the second loop only

$ 1 $ time. Then, on the next iteration of the outer loop, the first inner loop will only run

$ 3 $ times, while the second loop now runs

$ 2 $ times. Each time, the sum of the iterations will be

$ 5 $, so our lines will always be the same length.

When we run the code, we’ll get this output:

*

* *

* * *

* * * *

* * * * * Example 3

Up to this point, we’ve just been writing loops to print shapes using ASCII art. While that may seem trivial, understanding the “shape” that will be produced by a given set of nested loops can really help us understand how the code itself will function with other data.

Consider this example code:

total = 0

count = 0

for i in range(10):

for j in range(i + 1):

total = total + (i * j)

count += 1

print(f"sum: {total}, count: {count}")

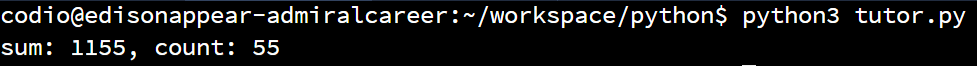

main()Before we even try to run this code, can we guess what the final value of the count variable will be? Put another way, can we determine how many times we’ll execute the code in the innermost loop, which will help us understand how long it will take for this program to run?

Let’s compare this code to the first example shown above:

for i in range(5):

for j in range(i + 1):

print("* ", end="")

print("")Notice how the code structure is very similar? The outermost loop runs a given number of times, and then the inner loop’s iterations are determined by the value of the outer loop’s iterator variable. Since we know that the second example produces a triangle, we can guess that the program above runs in a similar way. So, the first iteration of the outer loop will run the inner loop once, then twice on the second iteration, and so on, all the way up to $ 10 $ iterations. If we sum up all the numbers from $ 1 $ to $ 10 $, we get $ 55 $.

Now let’s run that code and see if we are correct:

As this example shows, we can use our basic understanding of various looping structures to help us understand more complex programs, and even predict their output without running or tracing the program. This is a very useful skill to learn when working with nested loops.