Lists & Functions

YouTube VideoResources

Earlier in this lab, we saw Python Tutor create a list variable within the frame of a function, but that variable actually pointed to a list object that was stored in the global objects list. As it turns out, this seemingly minor distinction is a very important concept to understand how lists and functions interact with each other.

To demonstrate what is going on, let’s explore a program that contains multiple functions that operate on lists using Python Tutor once again. For this example, consider the following Python program:

def increment_list(nums):

i = 0

while i < len(nums):

nums[i] = nums[i] + 1

i = i + 1

def append_sum(nums):

sum = 0

for i in nums:

sum = sum + i

nums.append(sum)

def main():

nums = [1]

for i in range(4):

increment_list(nums)

append_sum(nums)

print(nums)

main()Before we go through the full example, take a minute to read through the code and try to piece together how it works. For example, notice that the increment_list() and append_sum() functions do not return a value! Since they don’t return a value, will they really have any impact on the program itself?

To find out, let’s run through this program in Python Tutor. As always, you can copy the code to Python Tutor, or click this Python Tutor link to open it in a web browser.

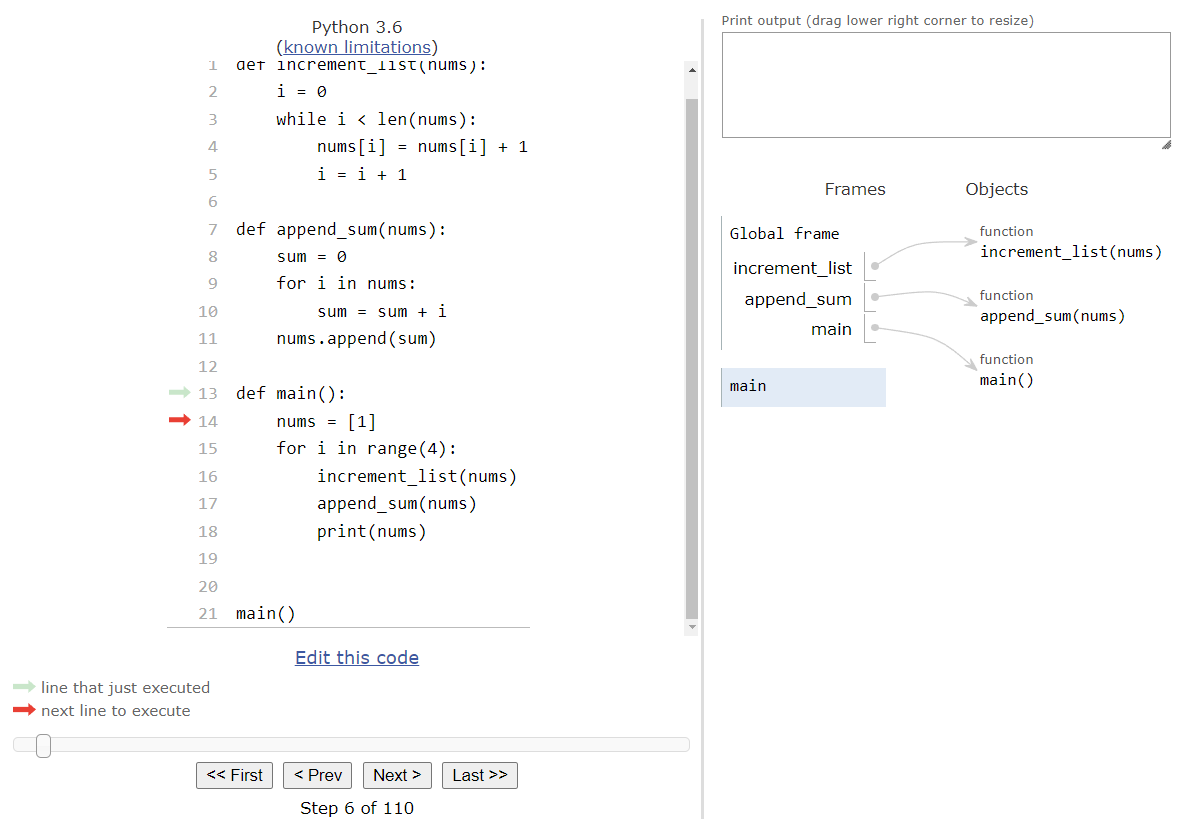

Python Tutor begins by adding all of the functions to the global frame, and then entering the main() function when it is called at the bottom of the code. Once the program enters the main() function, we should see this state:

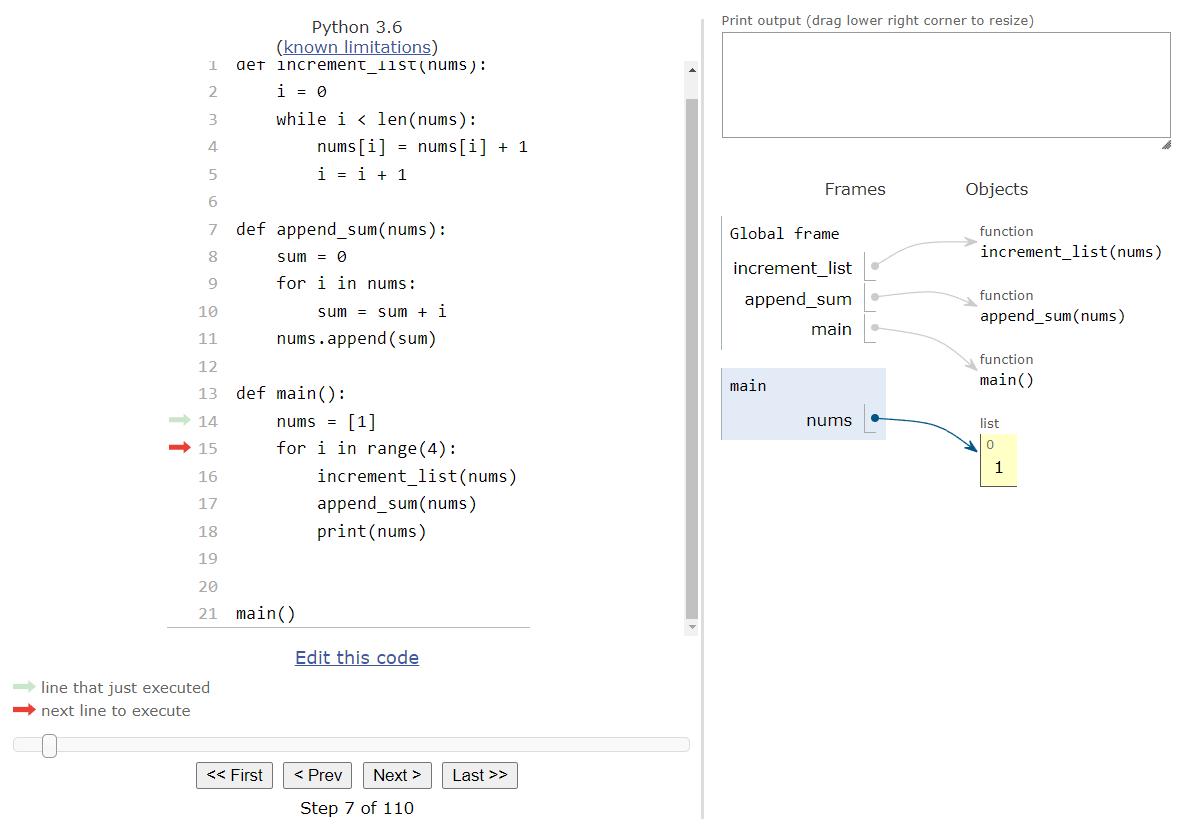

The main() function begins by creating a single list in the nums variable, which initially stores a single element, the number

$ 1 $. So, we’ll see the nums variable added to the main() function’s frame, with a pointer arrow to the list itself in the list of objects to the right:

Next, we’ll reach a for loop that will iterate

$ 4 $ times. So, we’ll store the first iterator value,

$ 0 $, in the iterator variable i and enter the for loop:

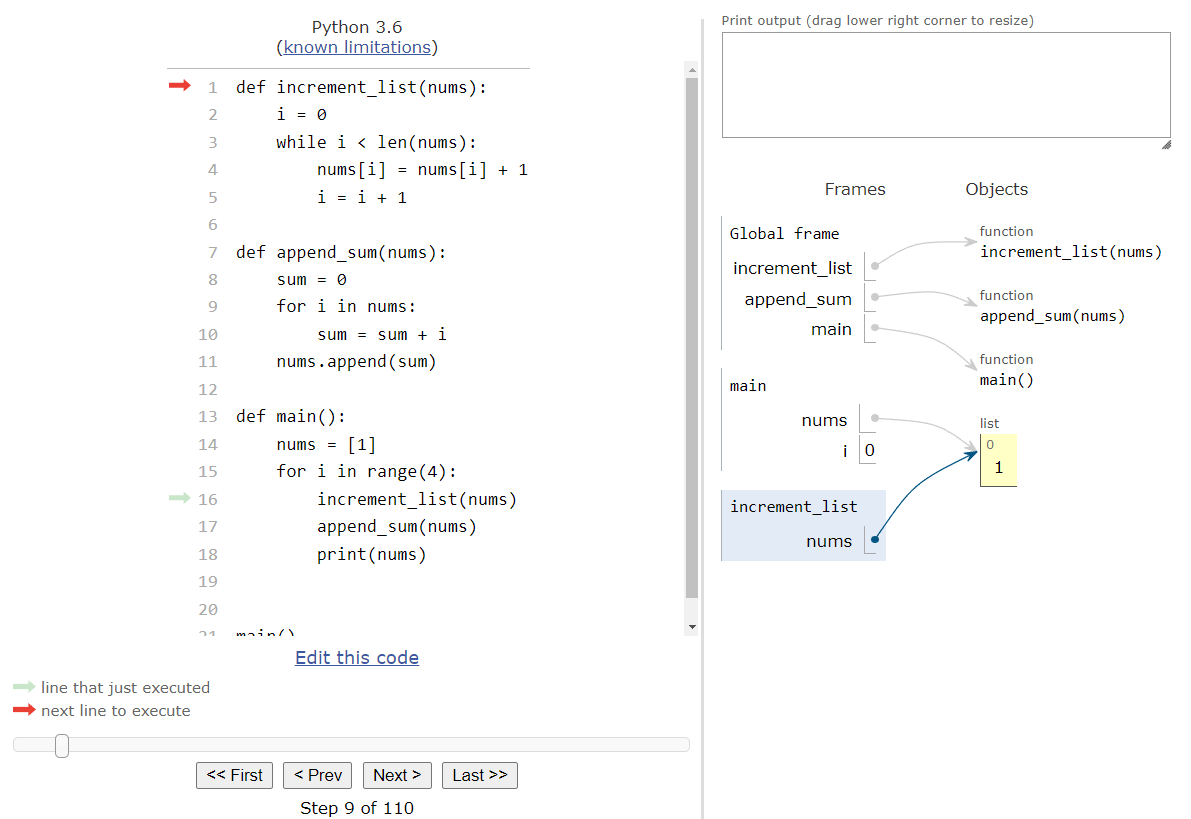

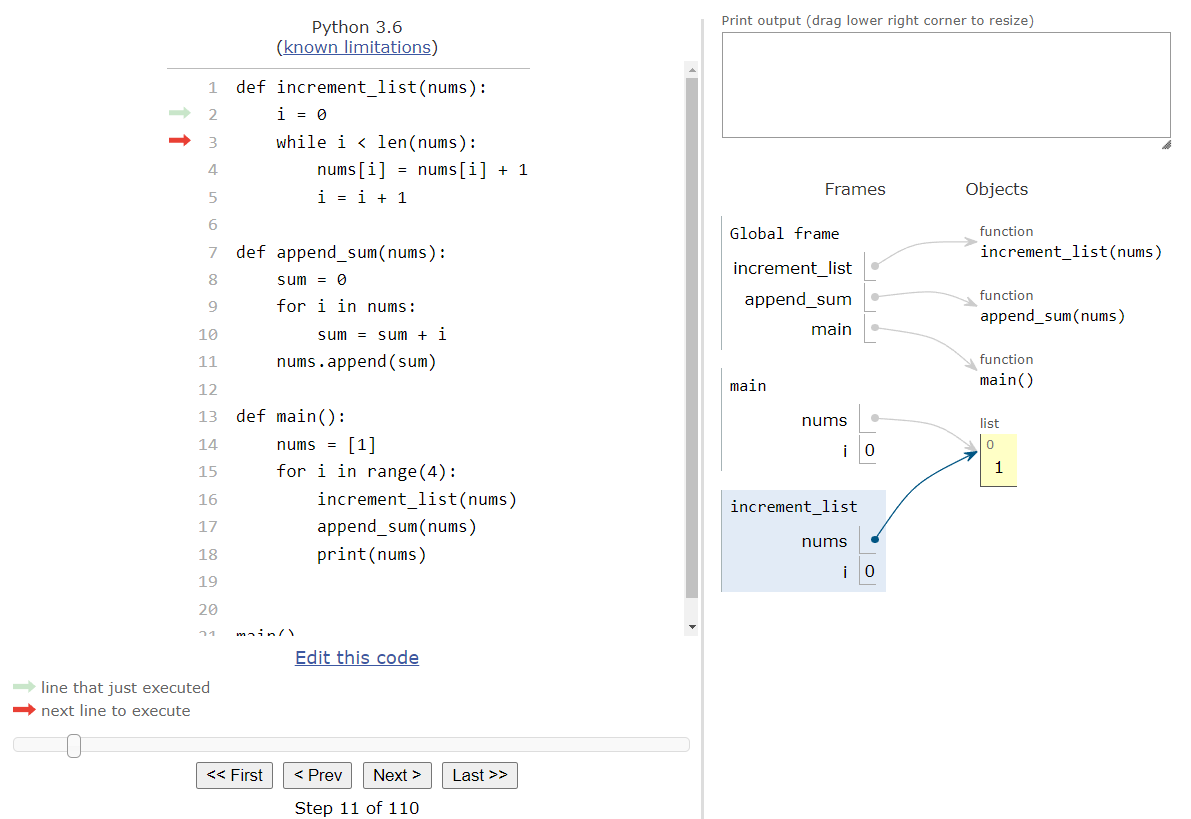

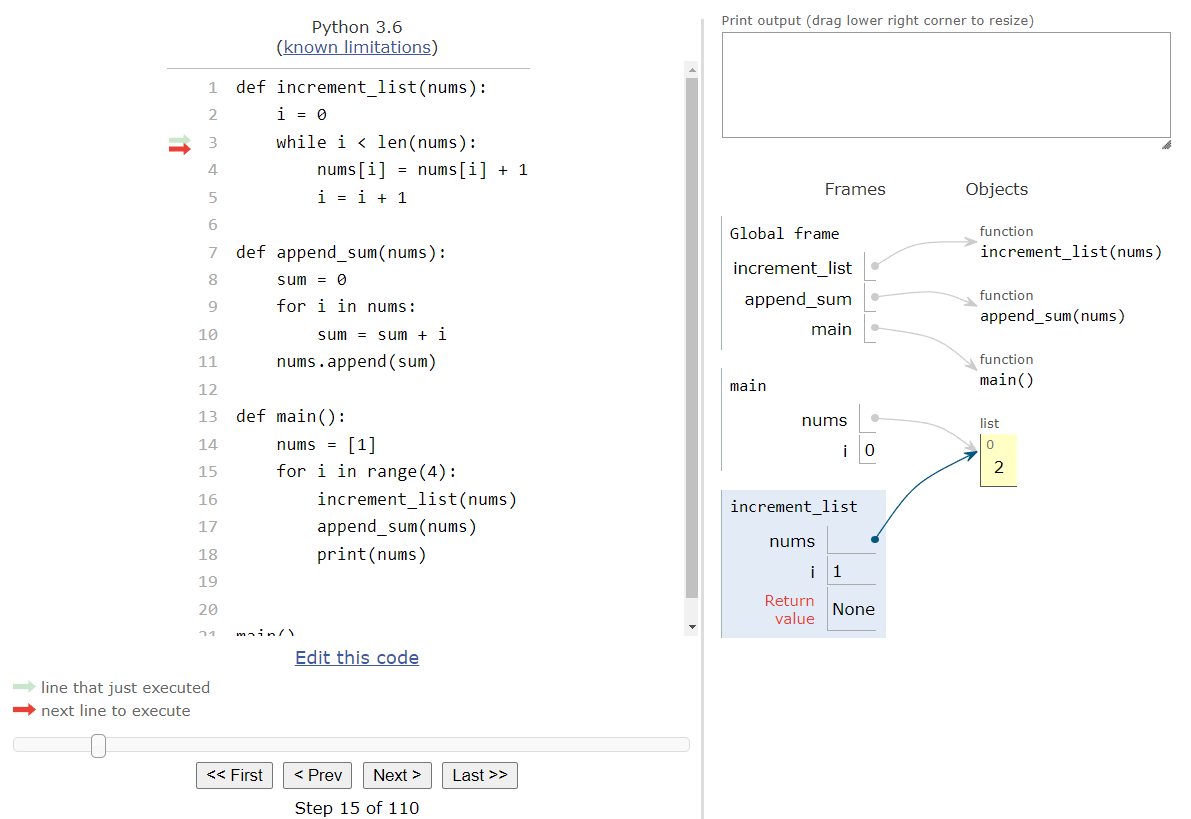

Inside of the for loop, the first step is to call the increment_list() function, which accepts a single parameter. So, we’ll provide the nums list as an argument to that function call. Just like always, Python Tutor will create a new frame for the increment_list() function when we call it, and it will populate all of the parameters for that function with the arguments that are provided, as shown here:

In this state, we see something interesting. In the increment_list() frame, we see the parameter nums is also a pointer to a list, but notice that it points to the exact same list object that the main() frame points to. This is because we are only sending the pointer to the increment_list() function so it knows where to find the list in the objects in memory, but it doesn’t actually duplicate the list.

In programming, we call this method of dealing with parameters call by reference, since we are simply passing references, or pointers, to the various objects but not the objects themselves. In technical terms, we’d say that the list is a mutable, or changeable, object, so we’ll use call by reference instead of the usual call by value process.

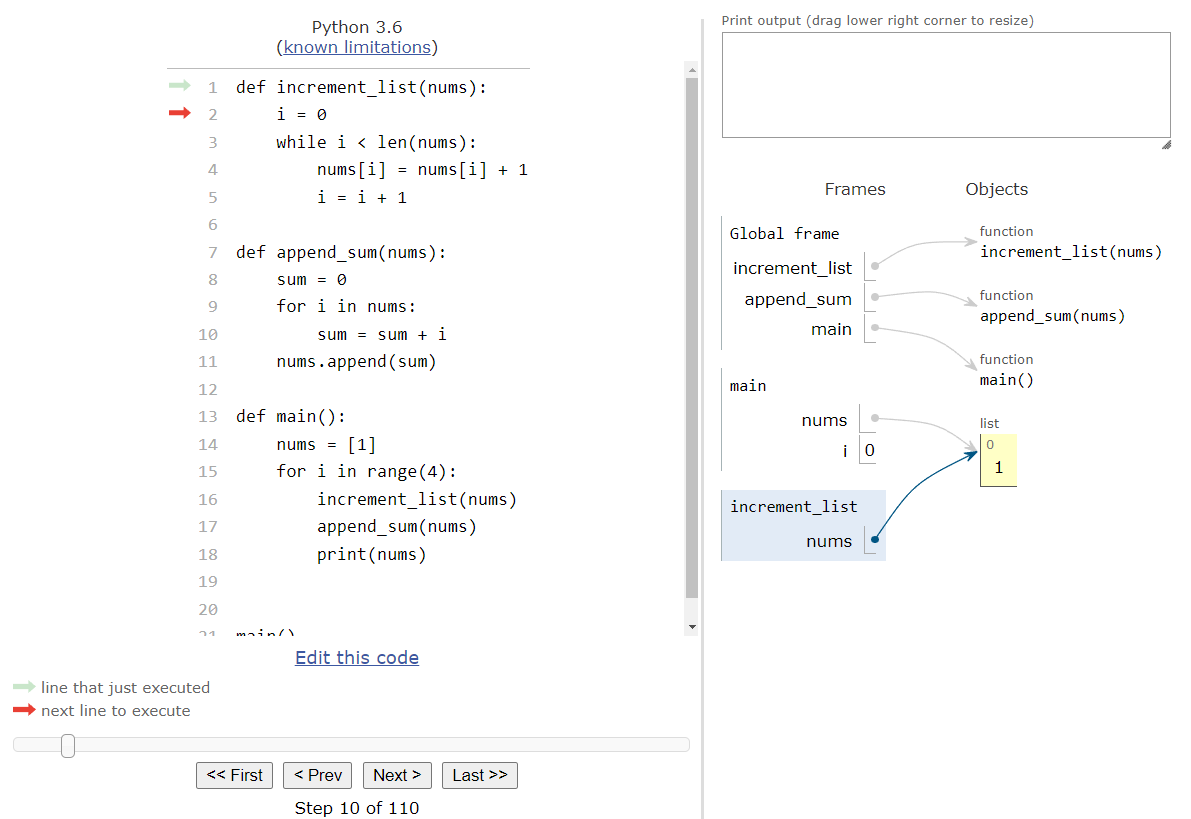

The next step will be to enter the increment_list() function itself:

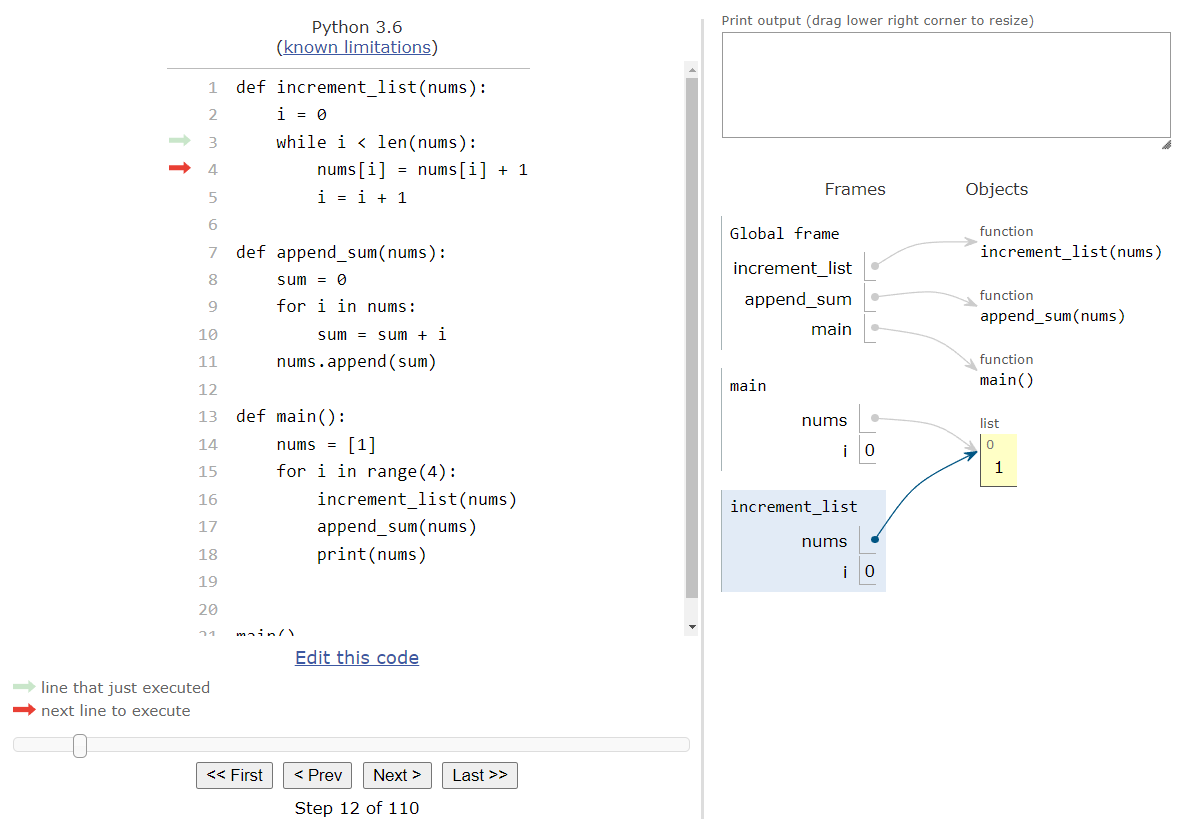

In this function, we are getting ready to use a while loop to iterate through the nums list. Since we’re going to be editing the values stored in the list, we should use a while loop instead of a for loop. So, we’ll start by setting the initial value of our iterator variable i to

$ 0 $, and then we’ll reach the while loop in code:

When we’ve reached the while loop, we’ll need to make sure that our iterator variable is less than the size of the list. Since i is currently storing

$ 0 $, and our list contains at least one item, this Boolean expression is True and we’ll enter the loop:

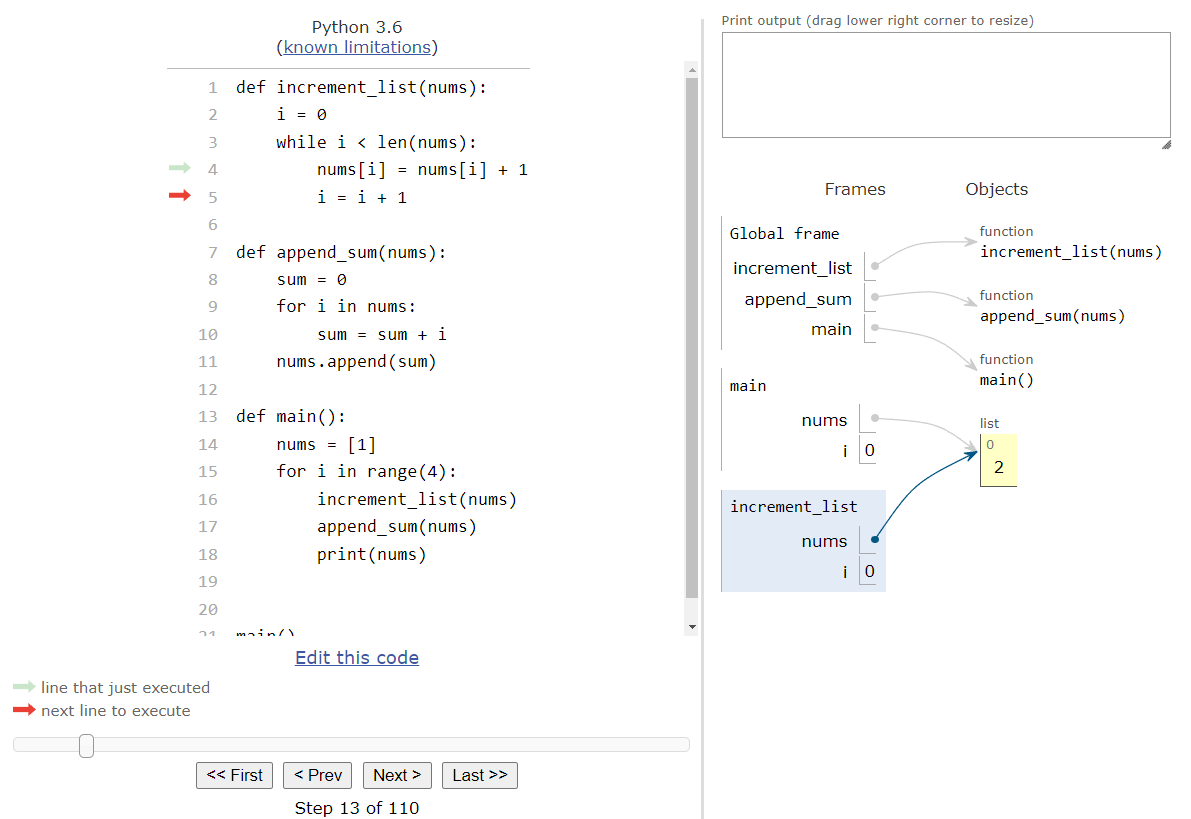

Inside of the loop, our goal is to increment each item in the list by

$ 1 $. So, we’ll use the iterator variable i inside of square brackets to both access the item in the list currently on the right-hand side of the assignment statement, and then we can also use it as the location we want to store the computed value, which is on the left-hand side of the assignment statement.

Then, we’ll increment our iterator variable i by

$ 1 $, and then jump back to the top of the loop:

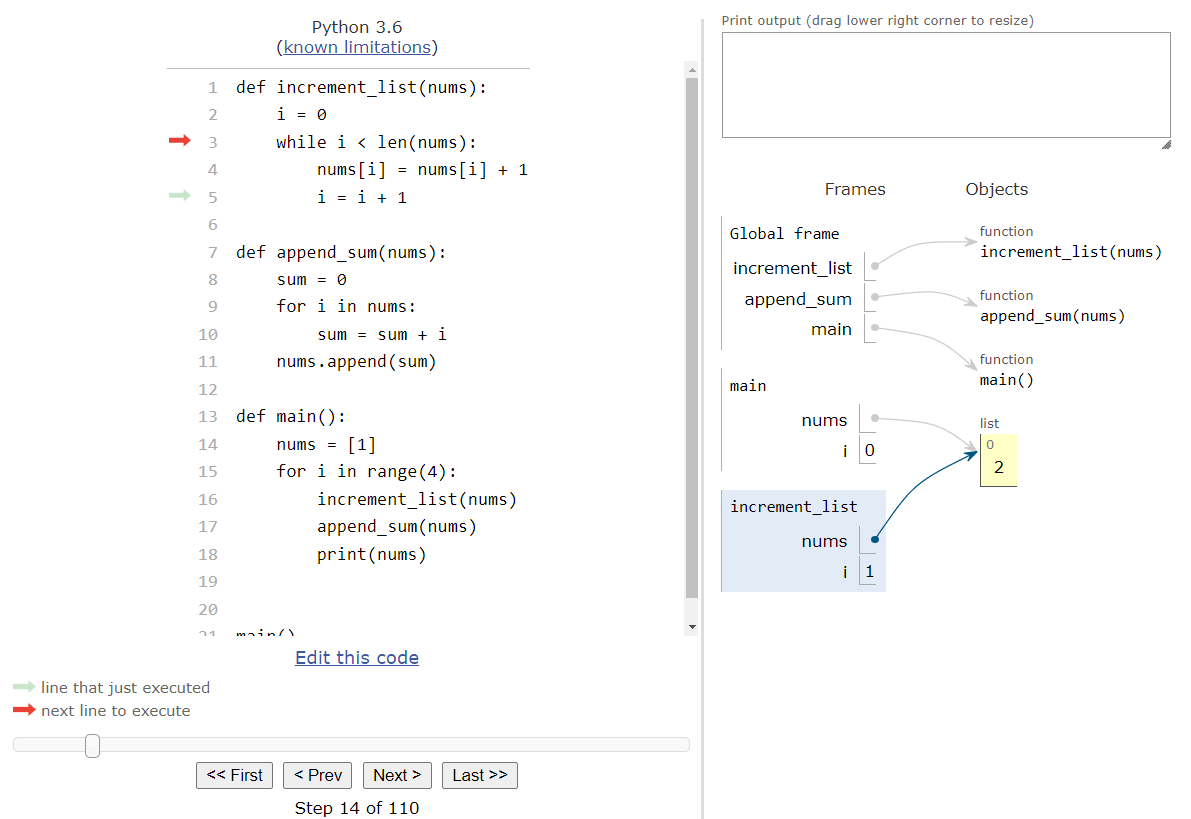

At this point, we must check our Boolean expression again. This time, our iterator variable i is storing

$ 1 $, but the length of the list is also

$ 1 $, so the Boolean expression is False and we should skip past the loop. Since there is no additional code in the increment_list() function after the loop, the function will simply return here.

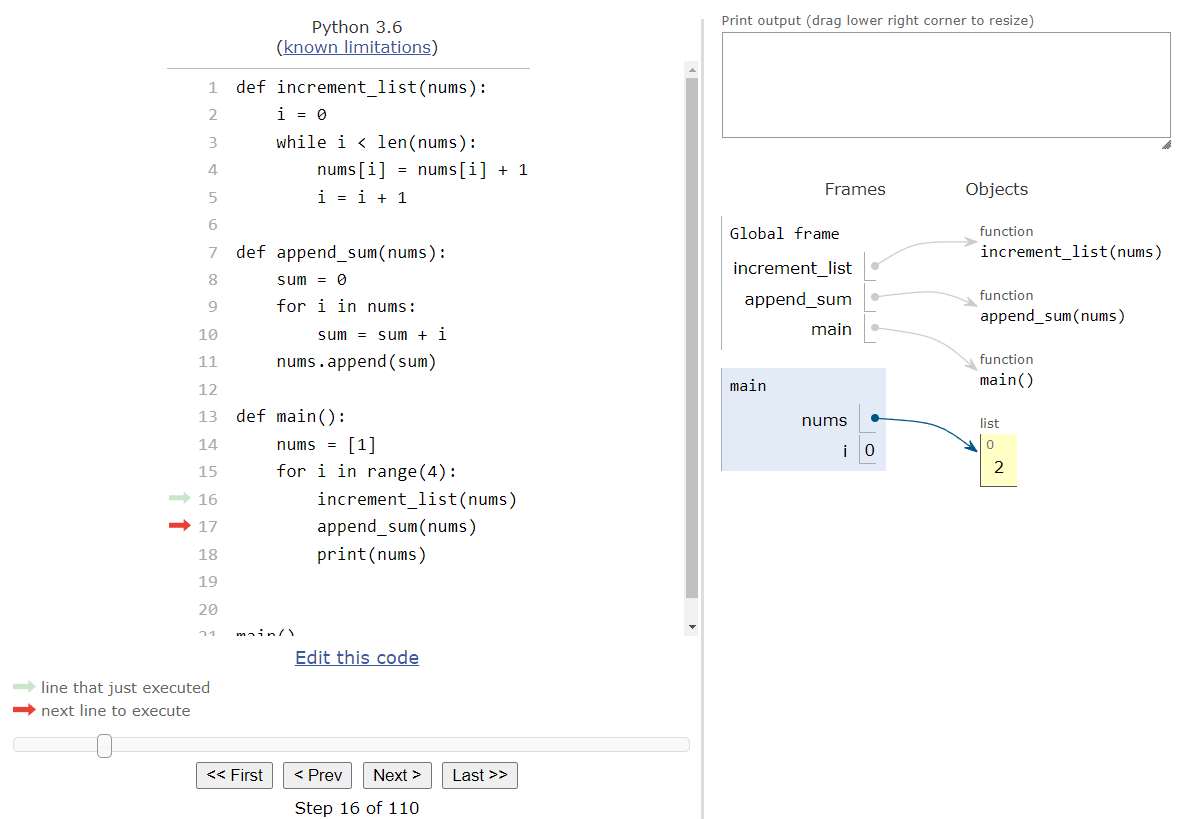

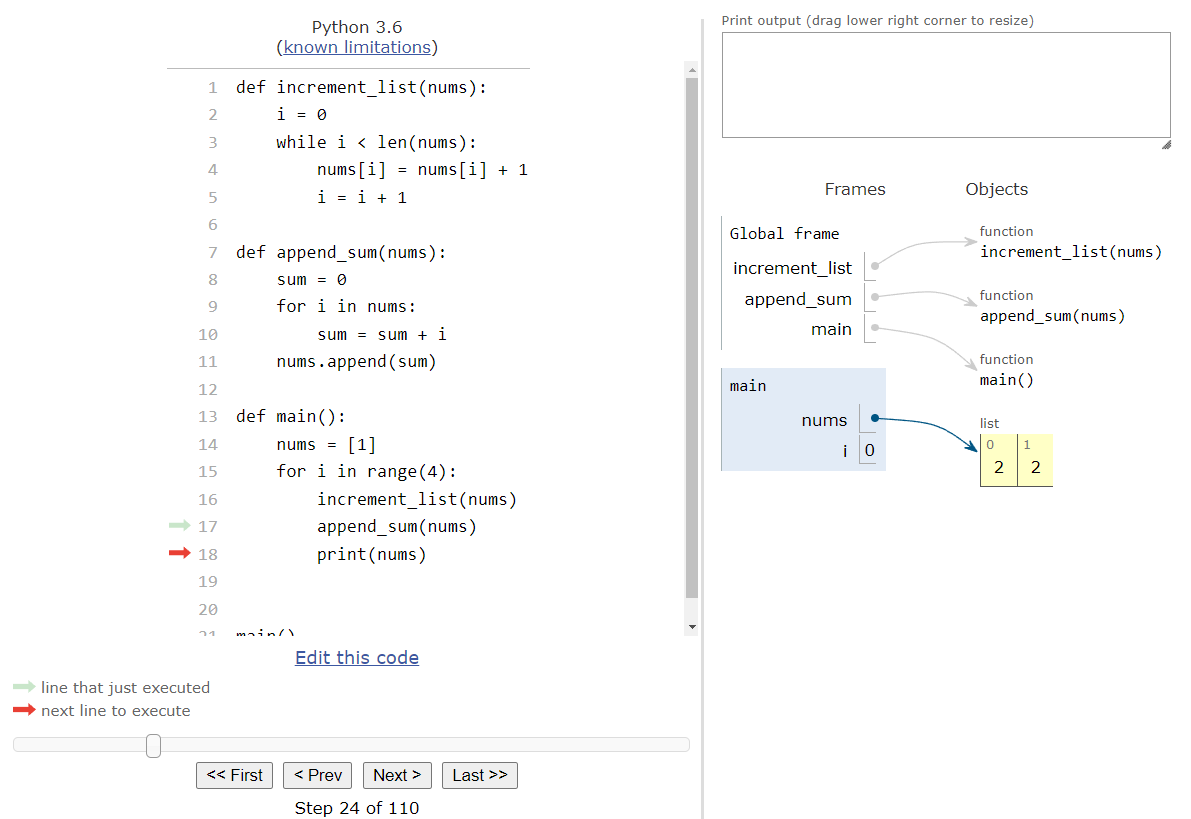

Notice that the function itself is not returning a value. Since Python uses call by reference, we don’t have to return the nums list back to the main() function even though we updated it, because the main() function still has a pointer to that exact same list object in memory. So, once the function returns, we’ll end up back in the main() function as shown here:

Notice that the frame for the increment_list() function is now gone, but the changes it made to the list are still shown in the list object to the right. This is why working with lists and functions can be a bit counter-intuitive, since it works completely differently than single variables such as numbers and Boolean values. A bit later in this lab, we’ll discuss how string values can be treated as lists, even though they are technically stored as single variable values.

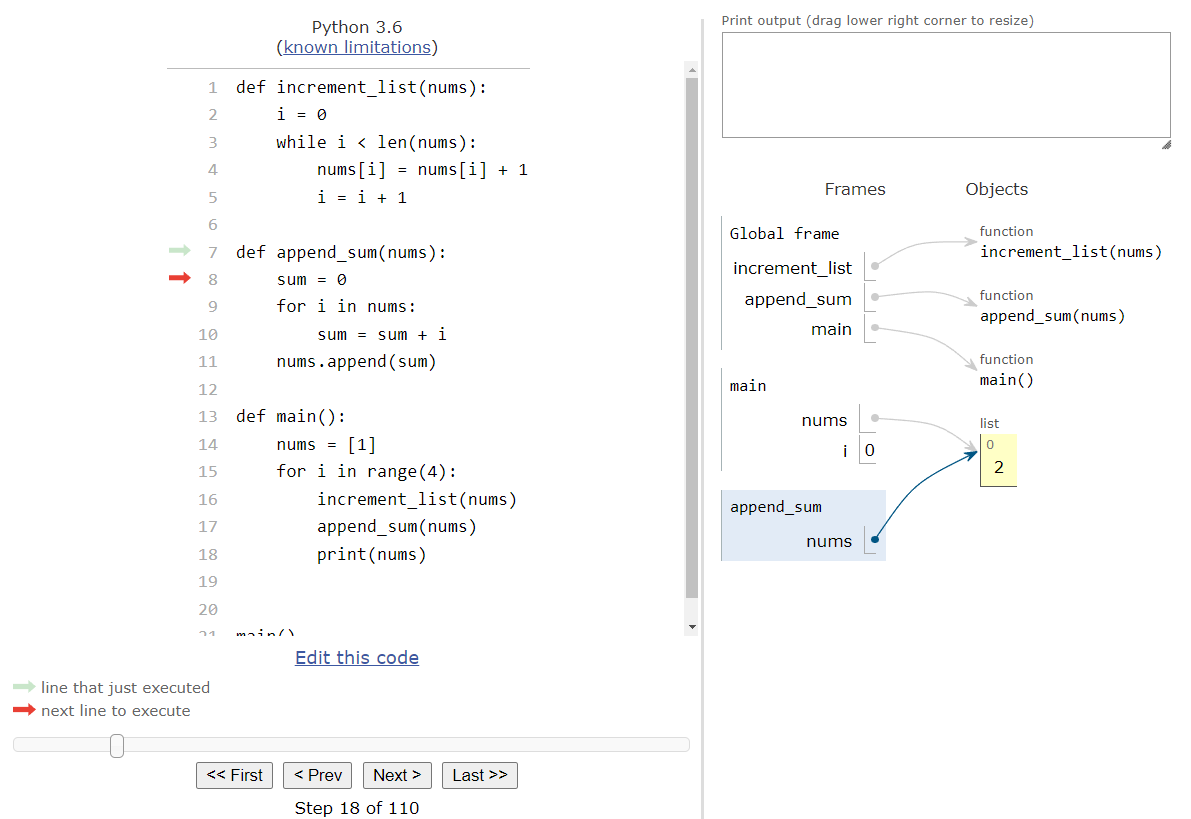

The next step in this program is to call the append_sum() method, using the same nums list as before. So, we’ll create a new frame for that function and populate it once again with a pointer to the nums list in memory - the very same nums list that the main() function is using:

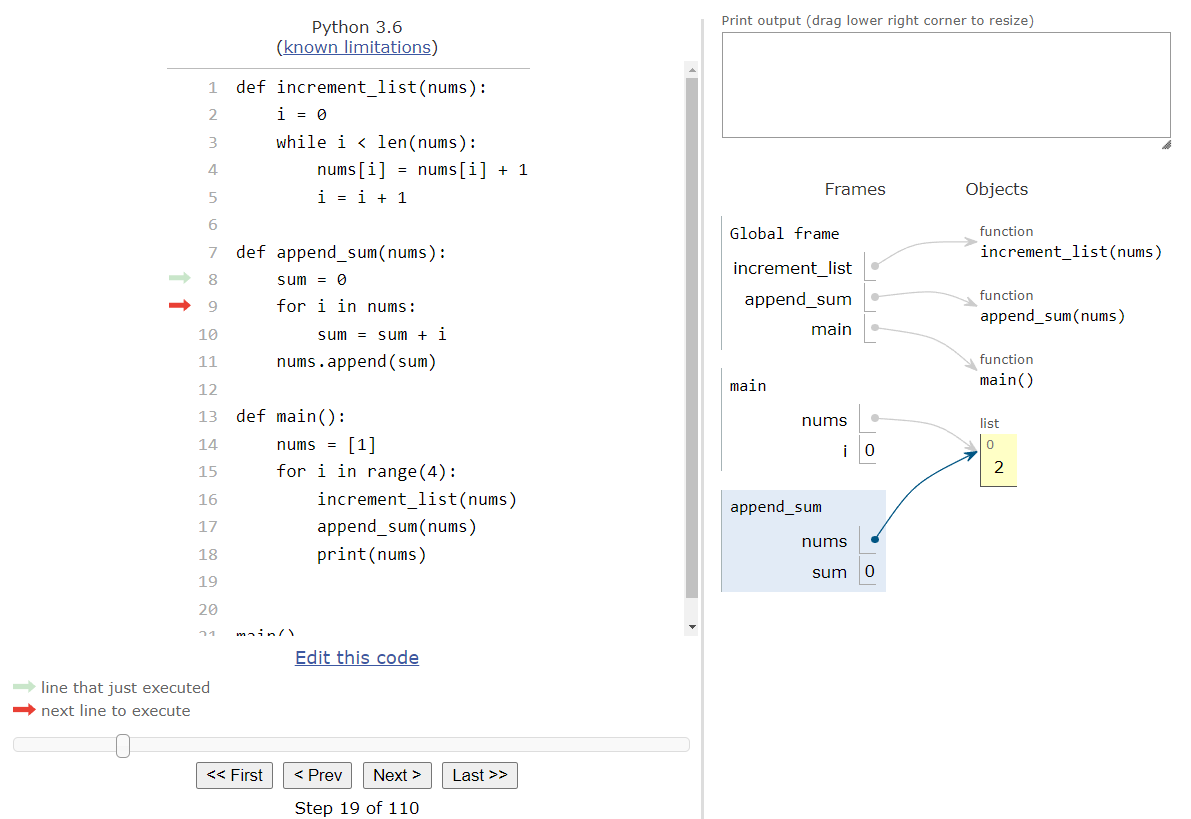

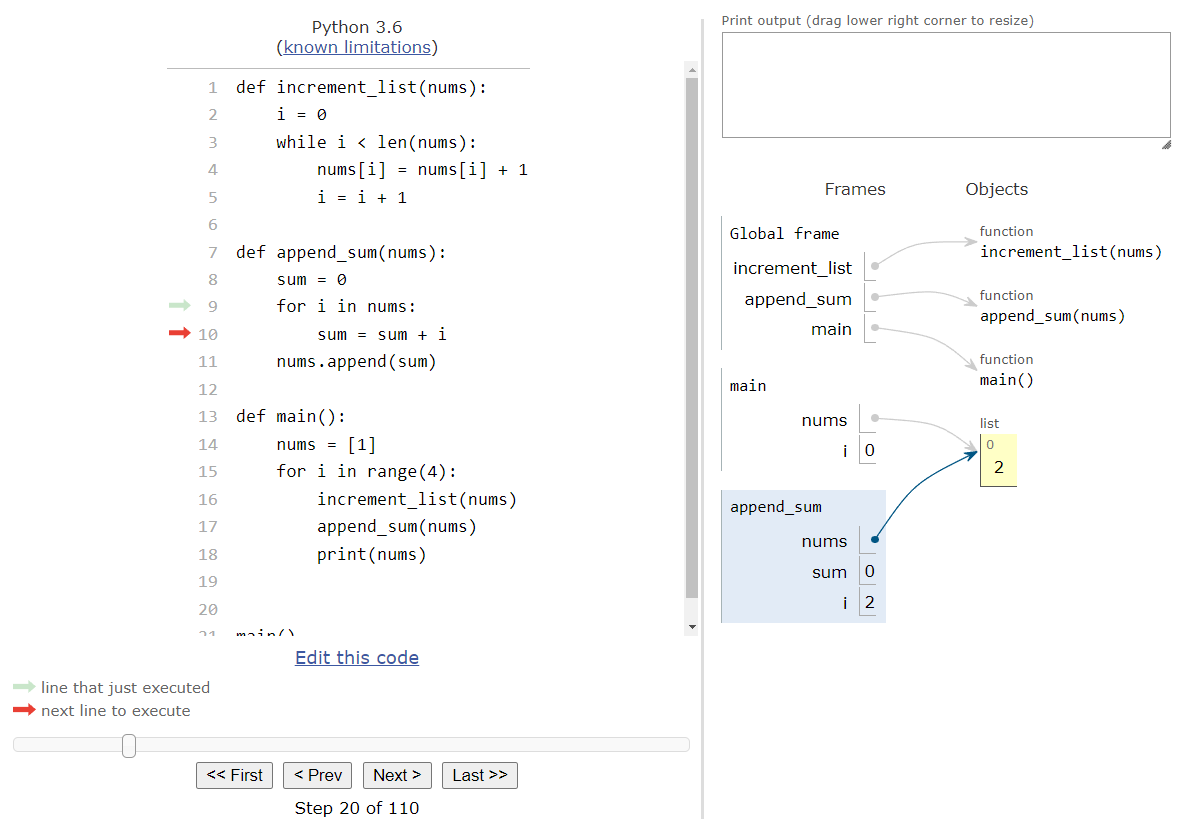

In the append_sum() function, our goal is to sum up all of the values currently in the list, and then append that value to the end of the list. So, we’ll need to create a sum variable to keep track of the total, which will initially store

$ 0 $:

Thankfully, since we are not going to update the list from within our loop, we can use a simple for loop to iterate through the list. So, we’ll start by storing the first value in the list,

$ 2 $, into our iterator variable i, and then we’ll enter the loop.

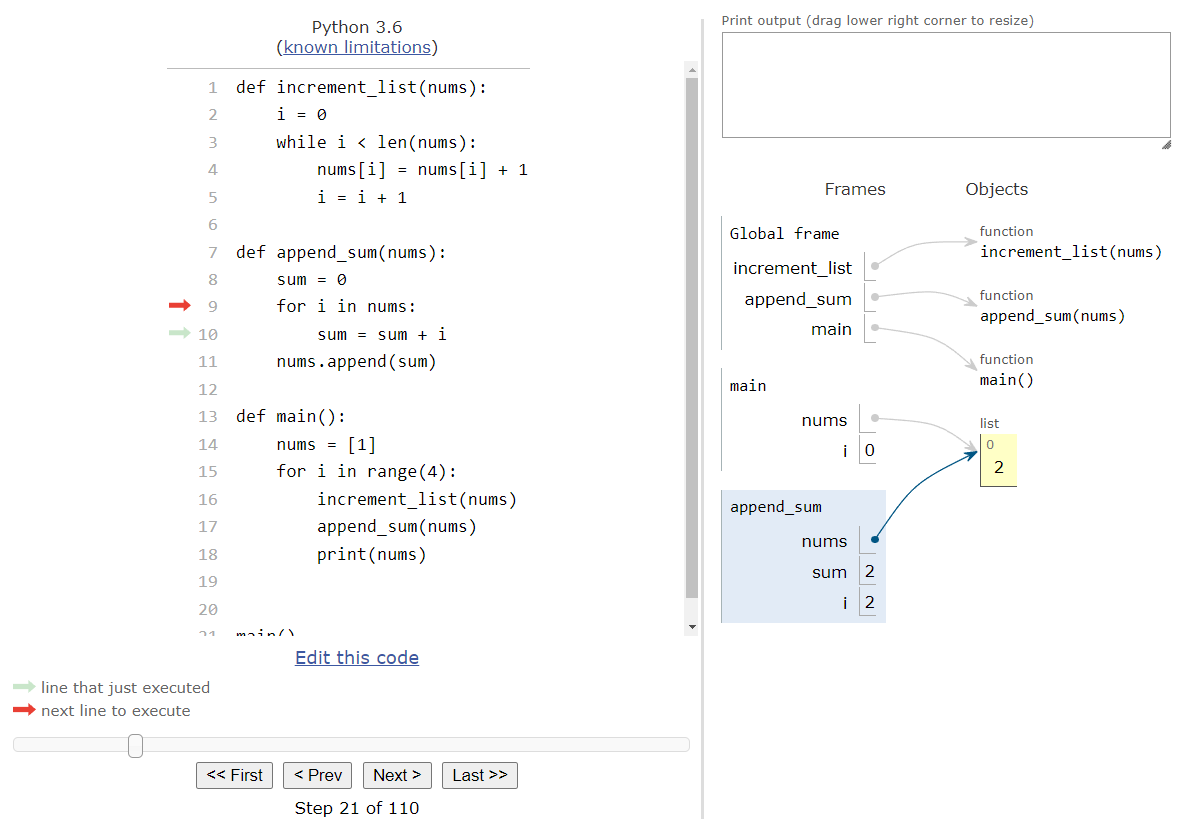

Inside of the loop, all we are doing is adding the value currently stored in i to the sum variable. So, we’ll store

$ 2 $ in sum and jump back to the top of the loop.

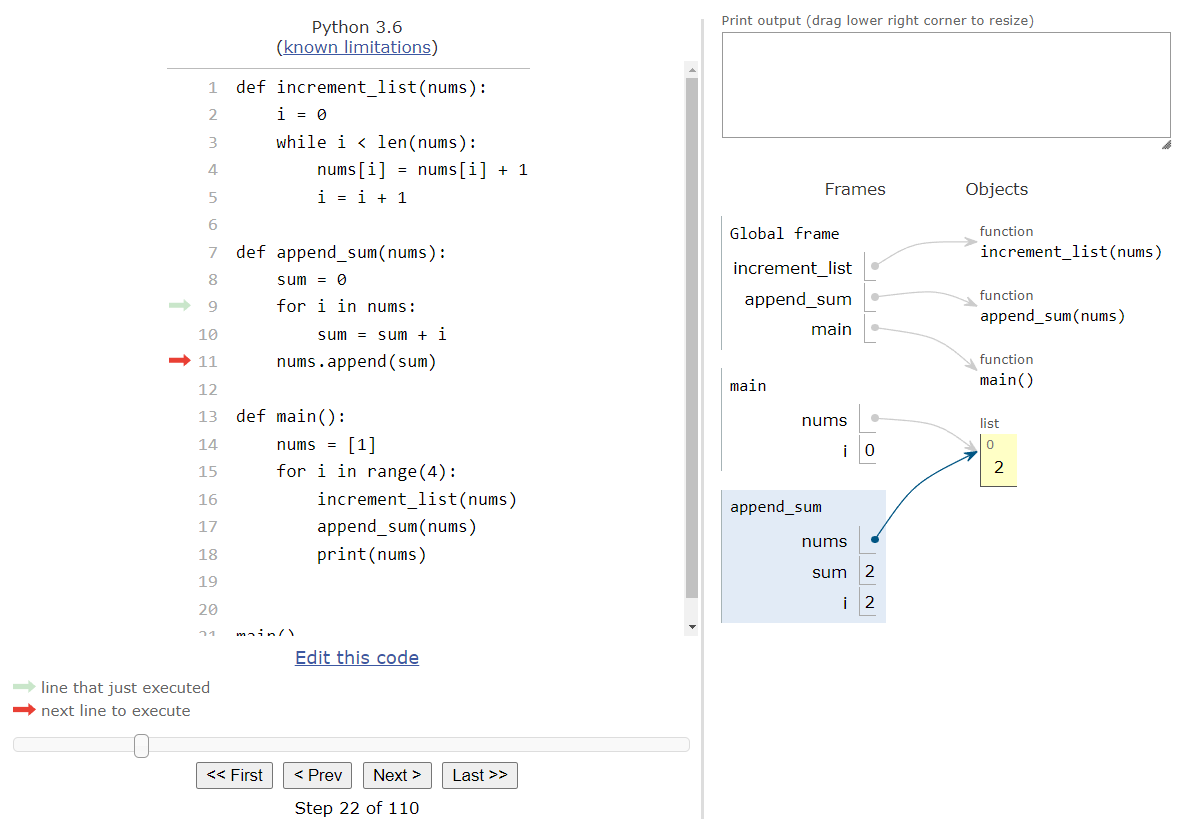

At this point, we’ve used every element in the list in our loop, so the loop will terminate and we’ll jump down to the code directly below the loop as shown here:

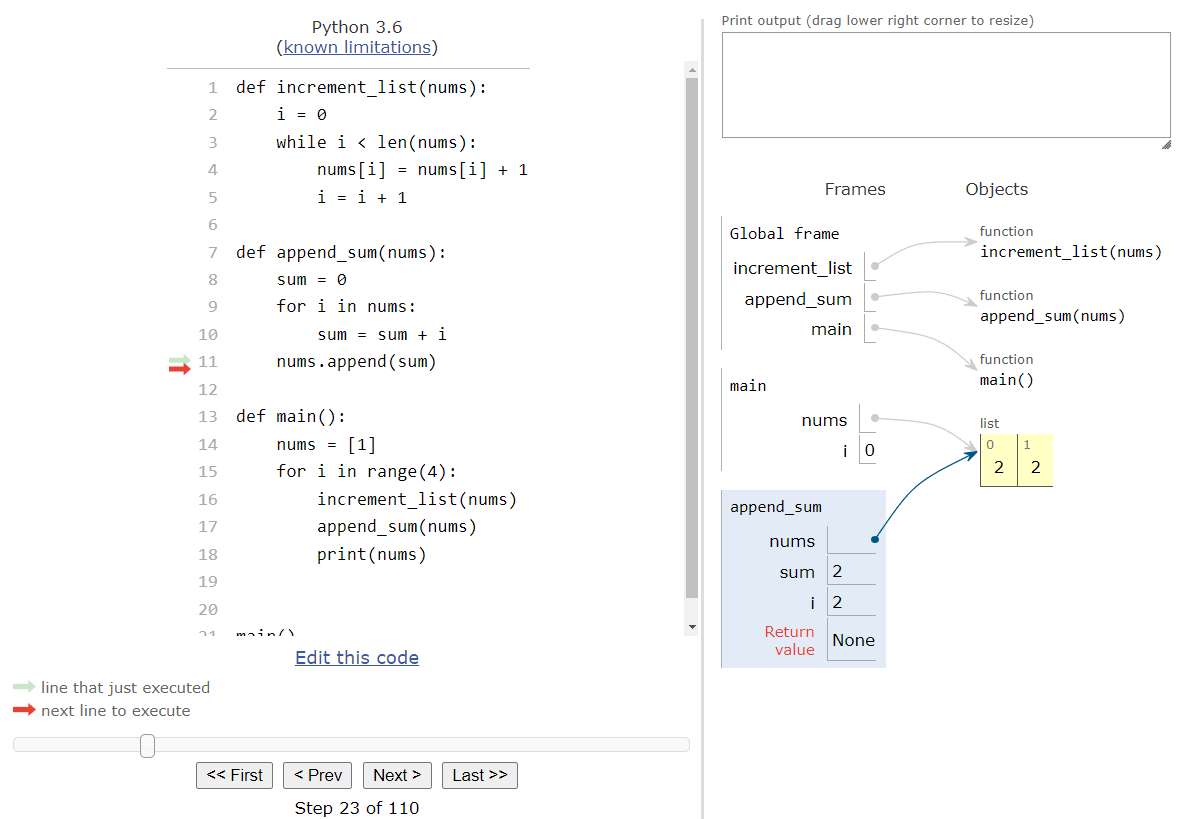

Finally, the last line of code in this function will append the value of sum to the end of the list.

At this point, we’ve modified the list to contain a new element. However, in Python Tutor we can clearly see that this item was just added to the existing list object in memory. So, when we get back to the main() function, we’ll be able to access the existing list, which will now include this new element as well.

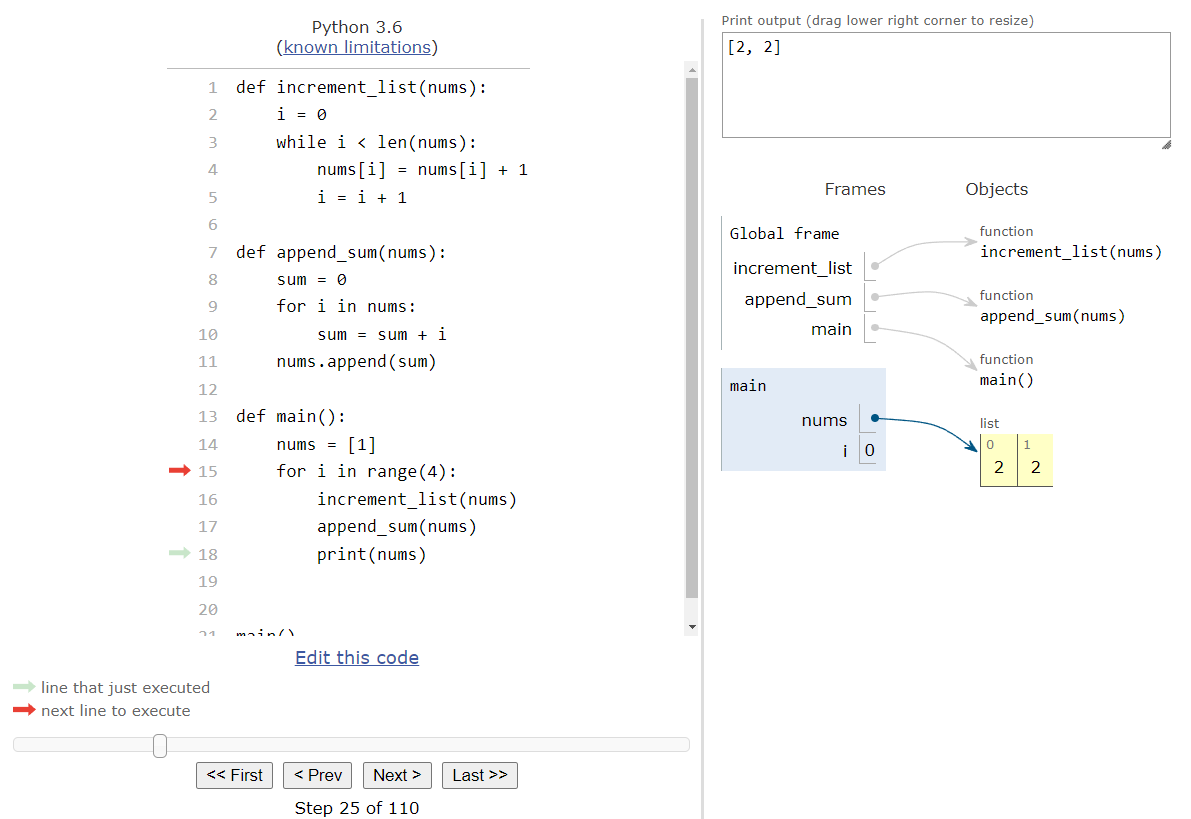

Back in the main() function, the last step in the loop is to print the current contents of the list to the terminal. So, after we execute that line, we should see some output in our print output box at the top right of the screen:

There we go! That’s one whole iteration through the loop in the main() function. This process will repeat

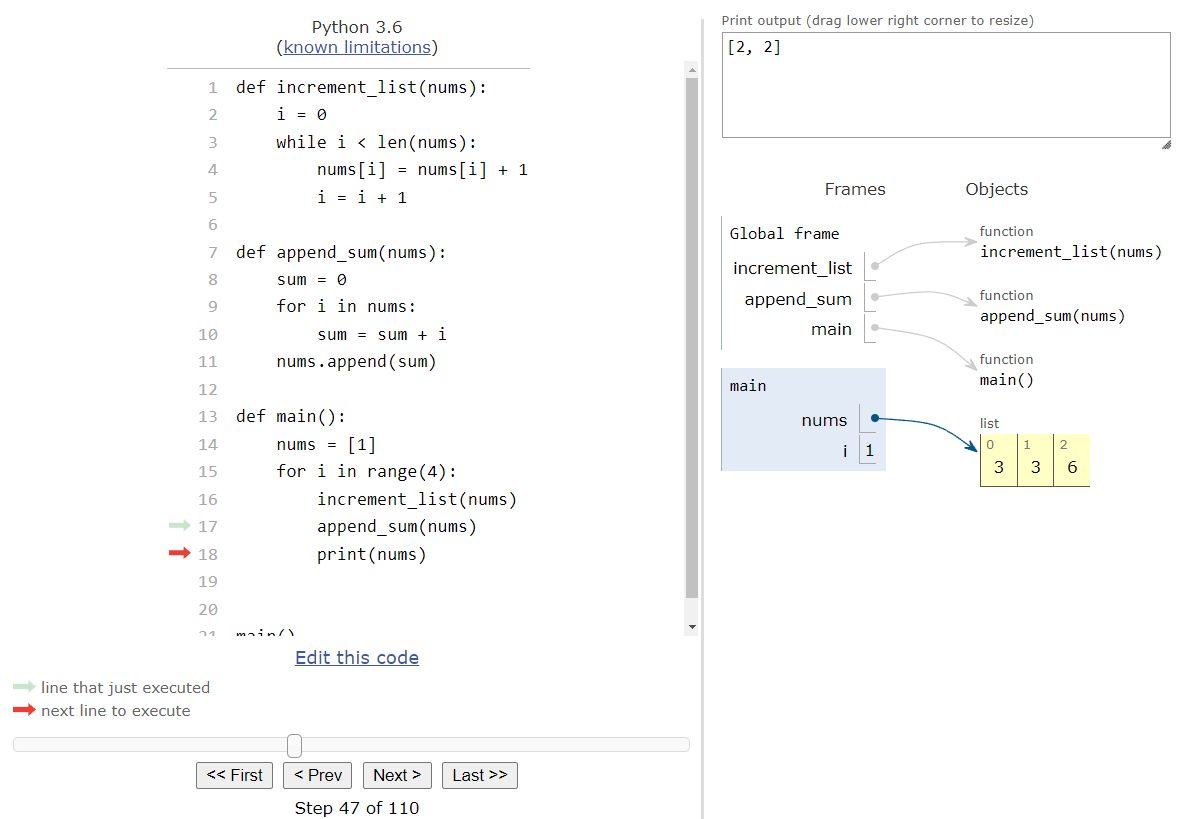

$ 3 $ more times. Each time, we’ll first increment the elements in the list using the increment_list() function, as shown here:

Then, we’ll sum up the existing elements in the list and append that value to the end of the list, which will result in this state:

Finally, we’ll print the contents of the list at that point, and jump back to the top of the loop:

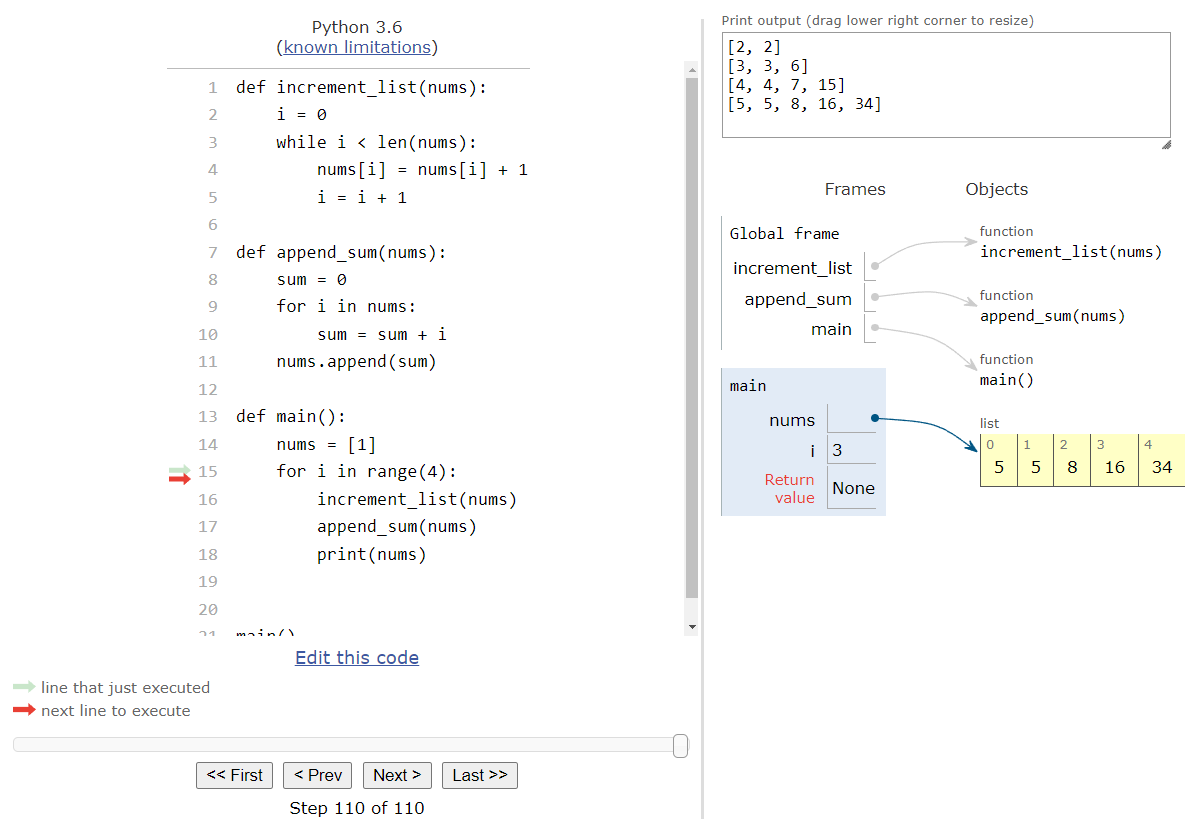

Each time, the list will be updated by the various functions that the main() function calls. Thankfully, since Python uses call by reference, each function is able to update the same list object in memory, making it quick and easy to work with lists and functions in Python. At the end of the entire program, we’ll see this state:

A full animation of this program, with some steps omitted, is shown here:

Functions that use lists as parameters are a very common technique in programming, and it is very important to understand how they work. If we aren’t careful, it is very easy to make a change to a list inside of a function call, and then later assume that the original list is unchanged. Likewise, if we pass a list as an argument to a function that works differently than we think it should, it could end up changing our data without us even noticing it. Hopefully this example makes it very clear how Python functions handle lists as parameters.