Introduction

The term “3D rendering” refers to converting a three-dimensional representation of a scene into a two-dimensional frame. While there are multiple ways to represent and render three-dimensional scenes (ray-tracing, voxels, etc.), games are dominated by a standardized technique supported by graphics card hardware. This approach is so ubiquitous that when we talk about 3D rendering in games, this is the approach we are typically referring to.

Remember that games are “real-time”, which means they must present a new frame every 1/30th of a second to create the illusion of motion. Thus, a 3D game must perform the conversion from 3D representation to 2D representation, plus update the game world, within that narrow span of time. To fully support monitors with higher refresh rates, this span may be cut further - 1/60th of a second for a 60-hertz refresh rate, or 1/120th of a second for a 120-hertz refresh rate. Further, to support VR goggles, the frame must be rendered twice, once from the perspective of each eye, which further halves the amount of time available for a single frame.

This need for speed is what has driven the adoption and evolution of graphics cards. The hardware of the graphics cards includes a graphics processing unit, a processor that has been optimized for the math needed to support this technique, and dedicated video memory, where the data needed to support 3D rendering is stored. The GPU operates in parallel with and semi-independently from the CPU - the game running on the CPU sends instructions to the GPU, which the GPU carries out. Like any multiprocessor program, care must be taken to avoid accessing shared memory (RAM or Video RAM) concurrently. This sharing of memory and transmission of instructions is facilitated by a low-level rendering library, typically DirectX or OpenGL.

MonoGame supports both, through different kinds of projects, and provides abstractions that provide a platform-independence layer, in the Xna.Framework.Graphics namespace. One important aspect of this layer is that it provides managed memory in conjunction with C#, which is a departure from most game programming (where the developer must manage their memory explicitly, allocating and de-allocating as needed).

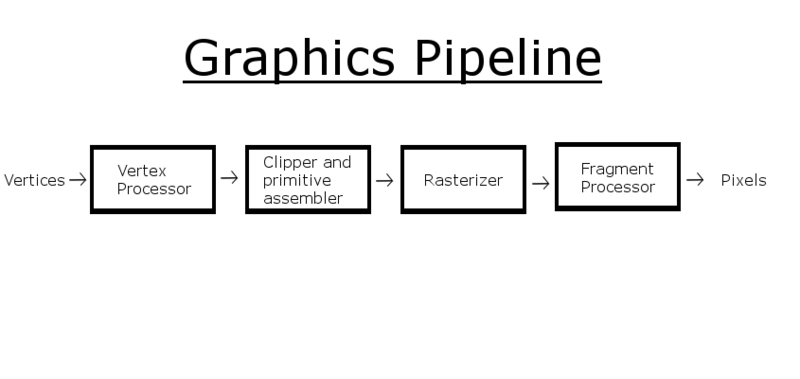

The Graphics Pipeline

This process of rendering using 3D accelerated hardware is often described as the Graphics Pipeline:

We’ll walk through this process as we write a demonstration project that will render a rotating 3D cube. The starter code for this project can be found on GitHub.