Class Attributes

Types of Attributes

There are two types of attributes: Class and Instance.

Class attributes are variables shared by all the instances (unique objects) in a class. They are typically things like constants, or information about how many objects of the class exists. For example a Stop_Light class may have the class attribute light _color = ['red', 'yellow', 'green'] to ensure all instances of Stop_Light use the same colors in the same order. A more complex version of our Student class might have a list of all in-use student_ids to ensure they are all unique.

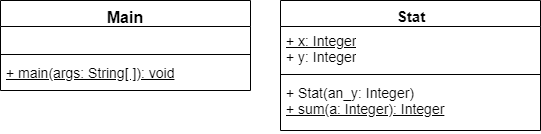

Class attributes are denoted on the UML diagram by underlining the attribute. In our example the Main-class contains Class Attributes.

Many programming languages include a special keyword static. In those languages, a static attribute or method is what Python calls a class attribute or method. CLass items are indicated on UML diagram by an underline. For Python, static-method and static-attribute are synonymous with class-.1

Class Attributes

In Python, any attributes declared outside of a method are class attributes, but they can be considered the same as static attributes until they are overwritten by an instance. Here’s an example:

class Stat:

x = 5 # class or static attribute

def __init__(self, an_y):

self.y = an_y # instance attributeIn this class, we’ve created a class attribute named x, and a normal attribute named y. Here’s a main() method that will help us explore how the static keyword operates:

from Stat import *

class Main:

def main():

some_stat = Stat(7)

another_stat = Stat(8)

print(some_stat.x) # 5

print(some_stat.y) # 7

print(another_stat.x) # 5

print(another_stat.y) # 8

Stat.x = 25 # change class attribute for all instances

print(some_stat.x) # 25

print(some_stat.y) # 7

print(another_stat.x) # 25

print(another_stat.y) # 8

some_stat.x = 10 # overwrites class attribute in instance

print(some_stat.x) # 10 (now an instance attribute)

print(some_stat.y) # 7

print(another_stat.x) # 25 (still class attribute)

print(another_stat.y) # 8

if __name__ == "__main__":

Main.main()First, we can see that the attribute x is set to 5 as its default value, so both objects some_stat and another_stat contain that same value. Interestingly, since the attribute x is static, we can access it directly from the class Stat, without even having to instantiate an object. So, we can update the value in that way to 25, and it will take effect in any objects instantiated from Stat.

Below that, we can update the value of x attached to some_stat to 10, and we’ll see that it now creates an instance attribute for that object that contains 10, shadowing the previous class attribute. The value attached to another_stat is unchanged.

You should avoid shadowing class attributes.

Class Methods

Python also allows us to create class methods that work in a similar way:

class Stat:

x = 5 # class or static attribute

def __init__(self, an_y):

self.y = an_y # instance attribute

def sum(a):

return Stat.x + aWe have now added a class method sum() to our Stat class.

In addition, it is important to remember that a static method cannot access any non-static attributes or methods, since it doesn’t have access to an instantiated object in the self parameter.

As a tradeoff, we can call class method without instantiating the class either, as in this example:

from Stat import *

class Main:

def main():

# other code omitted

Stat.x = 25

moreStat = Stat(7)

print(moreStat.sum(5)) # 30

print(Stat.sum(5)) # 30

if __name__ == "__main__":

Main.main()Alternative Syntax

Python supports an alternate syntax for methods. This form has not been widely adopted.

class Demo:

class_count = 0 # a class variable

def __init__():

self.name = None

def instance(self, name): # an instance method (note the self parameter)

# call <variable>.instance("text")

self.name = name # instance attribute

Demo.class_count += 1 # access a class attribute via class name

@classmethod

def print_count(cls): # class method

# call Demo.print_count()

print (cls.class_count) # access class variable via 'cls'

@staticmethod

def total_number(): # static method

# call Demo.total_number

return Demo.class_count # access a class attribute via class nameThere is no expressive power difference between an @classmethod and @staticmethod–the can access exactly the same things using slightly different syntax. The @staticmethod is called a decorator. The decorators tell the Python interpreter to handle the item that follows in a special way.

By convention, the object oriented programs start with a static main methods. We will follow that convention.

UML Class Diagrams

UML neatly side steps the static-vs-class nomenclature debate by using the term “classifer” for any item which belongs to the class and not the instance. According to the UML specification, any “classifer” items should be underlined, as in this sample UML diagram below:

Try It!

Type (or cut and paste) the code for the Stats class (in static/Stat.py) and Main (in static Main.py). Mark the main() method with an @staticmethod decorator. Now, we can use the buttons below to run the sample files open to the left to explore using class attributes and methods.

-

There are technical differences in the way languages store and access static and class items at the machine code level. We will ignore these differences. ↩︎