Code Coverage

We’ve now written our program, as well as a unit test that runs our program and make sure it works. But, how can we be sure that our unit tests are adequately testing every part of our program? For that, we have to rely on another tool to help us calculate the code coverage of our unit tests.

Install Coverage.py

Thankfully, there are many easy to use tools that will compute the code coverage of a set of tests. For Python, one of the most commonly used tools is the aptly-named Coverage.py. Coverage.py is a free code coverage library designed for Python, and it is easy to install.

As we’ve already learned, we could easily install it using pip. However, since we are now using tox and a requirements file, we need to make sure that we update our requirements file as well. One easy way to do that is to just update the requirements file to include the new library, then use pip to make sure everything is installed properly.

So, let’s open requirements.txt and make sure it now includes the following content:

coverage

pytest

pytest-html

toxOnce we’ve updated our requirements file, we can then install it by opening a Linux terminal, going to the python folder, and then using pip to install everything from the requirements list:

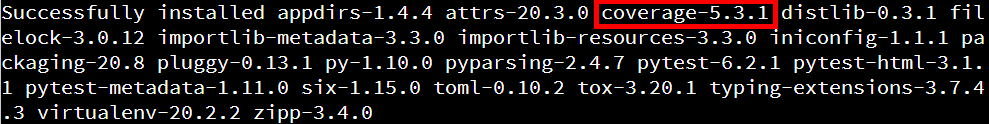

pip3 install -r requirements.txtAs you might guess, the -r command line argument for pip3 will allow us to install the requirements listed in a requirements file. Once we run that command, the last line of output will list the packages installed, and we should see that Coverage.py is now installed:

Compute Code Coverage with Coverage.py

Now that we’ve installed and configured Coverage.py, let’s execute it and see what happens. Coverage.py uses a two step process to compute the code coverage from a set of tests - first we must execute the tests using the Coverage.py tool, then we can use another command to generate a report. So, from within the python folder, we can run the following command:

python3 -m coverage run --source src -m pytest --html=reports/pytest/index.htmlThis command is getting pretty complex, so let’s break it down:

python3- as always, we are running these commands using Python 3. From here onward, we’ll run each library as as module in Python instead of running the commands themselves.-m coverage run- we want to execute the Coverage.pyruncommand. We use-mto tell Python that we are executing the Coverage.py library as a Python module--source src- this tells Coverage.py where our source code is located. It will compute the coverage only for files in that directory-m pytest- we also have to tell Coverage.py how to execute the tests, so we include a second-mfollowed bypytest. Basically, we are taking our existing command for pytest and adding a few bits in front of it for Coverage.py--html=reports/pytest/index.html- as we saw earlier, this will tell pytest to create and store a report of the test results.

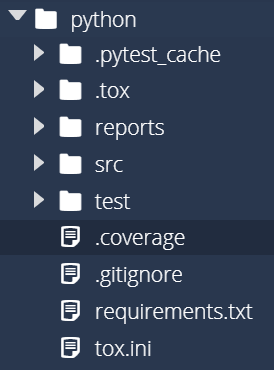

When we execute that command, it will tell Python to run our unit tests and generate a test report. Since we are now using Coverage.py to compute code coverage, we’ll also see a new file appear, named .coverage:

This file contains the data the Coverage.py collected from the unit tests. If needed, we can run multiple sets of unit tests and combine the data files using other Coverage.py commands. However, for now we won’t worry about that.

Once we’ve run our unit tests, we need to run one more command to generate a report. So, once again from within the python directory, run the following command:

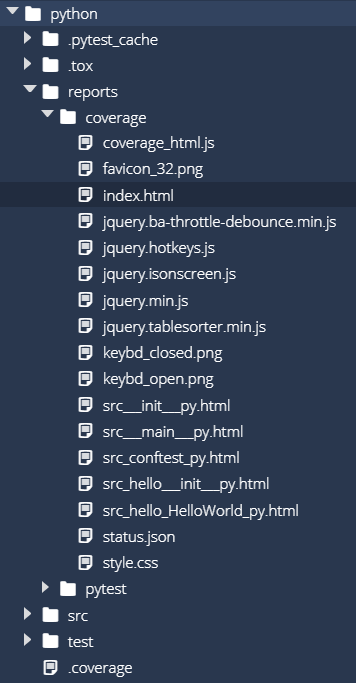

python3 -m coverage html -d reports/coverageThe coverage html command will generate a report, and the -d command line option sets the directory where the report will be stored. Once we execute this command, we should see the coverage directory structure appear in reports:

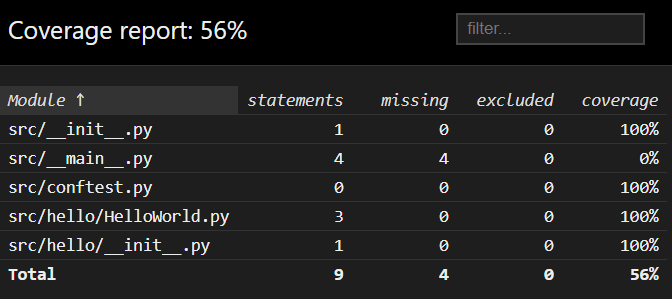

Inside of that folder is another index.html file. So, let’s right-click it and select Preview Static to open it as a webpage. Hopefully we should see something like this:

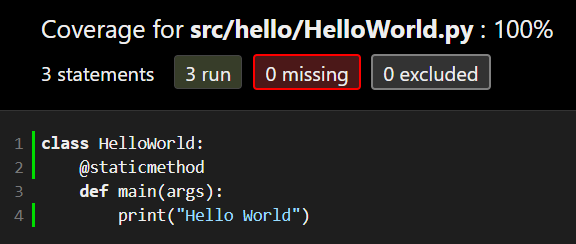

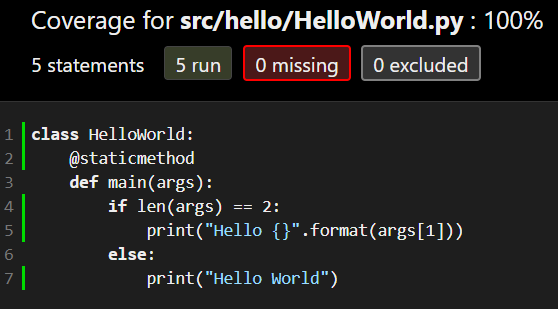

While our test only reports that it achieved 56% code coverage, we can see that it is because the __main__.py file was not executed. If we look at the other source files, we’ll see that we achieved 100% code coverage with our tests! That’s the goal, though it was pretty easy to achieve when our application really only contains one line of code. By clicking the links on the page, we can even see which lines are tested by our program, as shown below:

Code Coverage in Tox

Now that we have our Coverage.py library working, let’s update our tox configuration file to allow us to run those commands automatically via tox. All we have to do is open tox.ini in the python folder and update the commands section at the end of the file to look like this:

commands = python3 -m coverage run --source src -m pytest --html=reports/pytest/index.html

python3 -m coverage html -d reports/coverageNotice that those are the exact same commands we used earlier to execute our tests and generate a report using Coverage.py. That’s one of the most powerful features of tox - you are able to use the same commands within tox that you would use to manually execute the program.

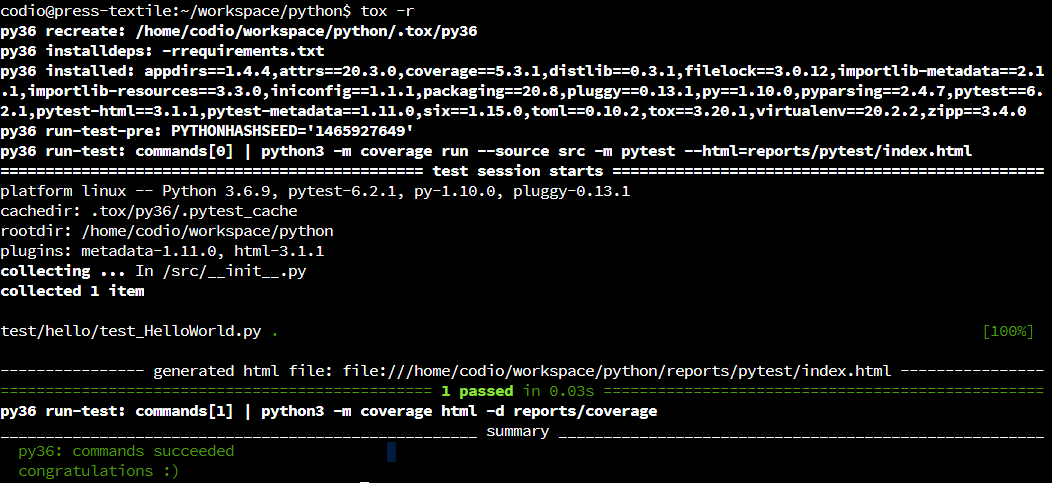

Once we’ve updated tox.ini, let’s run it once to make sure it works. This time, since we’ve installed a new requirement, we’ll need to tell tox to rebuild its environment by using the -r command line flag:

tox -rThat will tell tox to completely rebuild its virtual environment and reinstall any libraries listed in the requirements file.

We should once again be able to see tox execute our tests and generate a report:

More Complex Code

Let’s modify our application a bit and see how we can use Coverage.py to make sure we are really testing everything our application can do. In the HelloWorld.py file, found in src/hello, replace the existing code with this code:

class HelloWorld:

@staticmethod

def main(args):

if len(args) == 2:

print("Hello {}".format(args[1]))

else:

print("Hello World")This program will now print “Hello World” if executed without any command line arguments, but if one is provided it will use that argument in the message instead. So, let’s run our program again using this command from within the python folder:

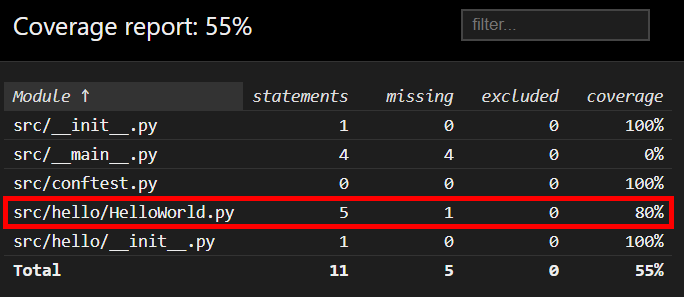

toxOnce the tests have finished, we can open the Coverage.py report stored in reports/coverage/index.html and we should find that it no longer achieves 100% coverage:

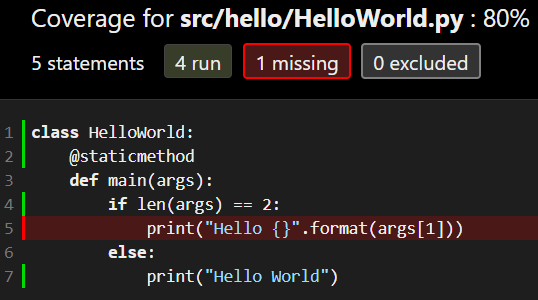

If we drill down deeper, we can find the lines of code that aren’t covered by our tests:

As we expected, our single unit test is not able to test each and every line of code in our application. That’s not good! So, we’ll need to update our tests to account for the change in our code.

Test-Driven Development

As a quick aside, if we were engaging in test-driven development, we would write the new unit test before changing the code. We won’t model that behavior right now, but it is worth noting that you don’t have to do these steps in the order presented here.

Update Unit Tests

So, let’s update our unit tests to account for this new code. There are a couple of ways we can do this:

- We can add more code to our existing

test_hello_worldmethod to call the method multiple times, both with and without arguments. - We can add additional test methods to test different behaviors.

In general, when working with unit tests, it is always preferred to add additional test methods to test additional functionality in the program. We want to keep our tests as simple and focused as possible, so that we can easily find the source of any errors it finds. If we simply added more code to the existing test, it would be difficult to tell exactly what caused the error. We’ll cover this in more detail when we formally discuss unit testing later in this course.

For now, let’s open the test_HelloWorld.py file stored in test/hello and add the following method to the TestHelloWorld class:

def test_hello_world_arg(self, capsys):

HelloWorld.main(["HelloWorld", "CC 410"])

captured = capsys.readouterr()

assert captured.out == "Hello CC 410\n", "Unexpected Output"Notice that this is nearly identical to the previous unit test method - we simply changed the arguments that are provided to the main method, and also updated the assertion to account for the changed output we expect to receive. As discussed earlier, there are things we can do to prevent duplication of code like this in our unit tests, but we won’t worry about that for now.

Once again, let’s rerun our tests using this command:

toxOnce that is done, we can open the JaCoCo report and see if we are back to 100% coverage:

If everything is working correctly, we should see that we are back at 100% coverage, and each line of code in our program is tested.

Of course, achieving 100% code coverage does not mean that you’ve completely tested everything that your application could possibly do - it simply means that you are at least testing every line of code at least once. It’s a great baseline to start with!

Git Commit and Push

This is a good point to stop and commit our code to our Git repository. So, like before, we’ll start by checking the status of our Git repository to see the files we’ve changed:

git statusIn that list, we should see everything we’ve updated listed in red. Next, we’ll add them to our index using this command:

git add .And then we can review our changes using the status command again:

git statusIf we are satisfied that everything looks correctly, we can commit our changes using this command:

git commit -m "Unit Tests and Code Coverage"And finally, we can push those changes to the remote repository on GitHub using this command:

git pushAs you can quickly see, this is a pretty short set of 5 commands that we can use to quickly store our code in our local Git repository and on GitHub. We just have to carefully pay attention to the files we commit and make sure it is correct.