Angular Dynamics

There is a second set of equations that govern angular motion (rotation) you may have encountered, where $ \omega $ is angular velocity, $ \alpha $ the angular acceleration, and $ \theta $ the rotation of the body:

$$ \omega = \omega_0 + \alpha t \tag{1} $$ $$ \theta = \theta_0 + \omega_0 t + \frac{1}{2}\alpha t^2 \tag{2} $$ $$ \theta = \theta_0 + \frac{1}{2}(\omega_0 + \omega)t \tag{3} $$ $$ \omega^2 = \omega_0^2 + 2\alpha(\theta-\theta_0) \tag{4} $$ $$ \theta = \theta_0 + \omega t - \frac{1}{2}\alpha t^2 \tag{5} $$

These equations parallel those we saw for linear dynamics, and in fact, have the same derivative relationships between them:

$$ \theta(t) \tag{6} $$ $$ \omega(t) = \theta'(t) \tag{7} $$ $$ \alpha(t) = \omega'(t) \tag{8} $$

And, just like linear dynamics, we can utilize this relationship and our small timestep to sidestep complex calculations in our code. Thus, we can calculate the rotational change from the angular velocity (assuming float rotation, angularVelocity, and angularAcceleration values expressed in radians):

rotation += angularVelocity * gameTime.elapsedGameTime.TotalSeconds;And the change in angular velocity can be calculated from the angular acceleration:

angularAcceleration = angularVelocity * gameTime.elapsedGameTime.TotalSeconds;Finally, angular acceleration can be imposed with an instantaneous force. However, this is slightly more complex than we saw with linear dynamics, as this force needs to be applied somewhere other than the center of mass. Doing so applies both rotational and linear motion to an object. This rotational aspect is referred to as torque, and is calculated by taking the cross product of the force’s point of application relative to the center of mass and the force vector. Thus:

$$ \tau = \overline{r} x \overline{F} $$Where $ tau $ is our torque, $ \overline{r} $ is the vector from the center of mass to where the force is applied, and $ \overline{F} $ is the force vector.

torque = force.X * r.Y - force.Y * r.X;Torque is the force imposing angular acceleration, and can be applied directly to the velocity:

angularAcceleration += torque * gameTime.ElapsedGameTime.TotalSeconds;And much like force and linear acceleration, multiple torques applied to an object are summed.

XNA does not define the cross product function in its Vector2 library, so we computed it manually above. If you would like to add it as a method in your projects, we can do so using an extension method, i.e. define in one of your game’s namespaces:

public static class Vector2Extensions {

/// <summary>

/// Computes the cross product of two Vector2 structs

/// </summary>

/// <param ref="a">The first vector</param>

/// <param ref="b">The second vector</param>

public static float CrossProduct(Vector2 a, Vector2 b)

{

return a.X * b.Y - a.Y * b.X;

}

/// <summary>

/// Computes the cross product of this vector with another

/// </summary>

/// <param ref="other">the other vector</param>

public static float Cross(this Vector2 a, Vector2 other)

{

return CrossProduct(a, other);

}

}As long as this class is in scope (i.e. you have an appropriate using statement), you should be able to invoke Cross() on any Vector2. So the code listing:

torque = force.X * r.Y - force.Y * r.X;Could be rewritten as:

torque = force.Cross(r);

Rocket Thrust

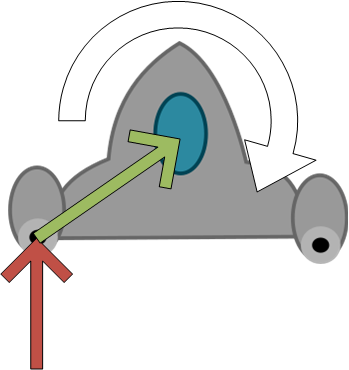

Let’s work through an example. Consider this diagram:

The red arrow is the force vector applied from the left rocket. The green arrow is the vector from the position the force is applied to the center of mass of the ship. Firing just this one rocket will impose a rotation on the ship in the direction of the white arrow. Firing both rockets will impose an opposite torque, cancelling both.

Let’s write the control code for this spaceship. We’ll define class fields for both linear and angular velocity and acceleration, as well as position, direction, and angle. We’ll also supply a constant for the amount of linear acceleration applied by our spaceship:

// Constants

float LINEAR_ACCELERATION = 10;

// Linear movement fields

Vector2 position;

Vector2 direction;

Vector2 velocity;

// Angular movement fields

float angle;

float angularVelocity;Then we’ll use these in our update method:

public void Update(GameTime gameTime)

{

KeyBoardState keyboardState = Keyboard.GetState();

float t = (float)gameTime.ElapsedGameTime.TotalSeconds;

Vector2 acceleration = Vector2.Zero; // linear acceleration

float angularAcceleration = 0; // angular acceleration

// Determine if the left rocket is firing

if(keyboardState.IsKeyPressed(Keys.A))

{

// LABEL A: Apply linear force in the direction we face from left rocket

acceleration += direction * LINEAR_ACCELERATION * t;

// TODO 1: Calculate and apply torque from left rocket

}

// Determine if the right rocket is firing

if(keyboardState.IsKeyPressed(Keys.D))

{

// LABEL B: Apply linear force in the direction we face from right rocket

acceleration += direction * LINEAR_ACCELERATION * t;

// TODO 2: Calculate and apply torque from right rocket

}

// Update linear velocity and position

velocity += acceleration * t;

position += velocity * t;

// update angular velocity and rotation

angularVelocity += angularAcceleration * t;

angle += angularVelocity * t;

// LABEL C: Apply rotation to our direction vector

direction = Vector2.Transform(Vector2.UnitY, new Matrix.CreateRotationZ(theta));

}There’s a lot going on in this method, so let’s break it down in pieces, starting with the code following the LABEL comments:

LABEL A & B - Apply linear force in the direction we face from left rocket and right rocket

When we apply force against a body not toward its center, part of that force becomes torque, but the rest of it is linear acceleration. Technically, we can calculate exactly what this is with trigonometry. But in this case, we don’t care - we just want the ship to accelerate in the direction it is facing. So we multiply the direction vector by a constant representing the force divided by the mass of our spaceship (acceleration), and the number of seconds that force was applied.

Note that we consider our spaceship mass to be constant here. If we were really trying to be 100% accurate, the mass would change over time as we burn fuel. But that’s extra calculations, so unless you are going for realism, it’s simpler to provide a constant, a lá LINEAR_ACCELERATION. Yet another example of simplifying physics for games.

LABEL C - Apply rotation to our direction vector

We need to know the direction the ship is facing to apply our linear acceleration. Thus, we need to convert our angle angle into a Vector2. We can do this with trigonometry:

direction.X = (float)Math.Cos(theta);

direction.Y = (float)Math.Sin(theta);Or we can utilize matrix operations:

direction = Vector2.Transform(Vector2.UnitY, new Matrix.CreateRotationZ(theta));We’ll discuss the math behind this second method soon. Either method will work.

TODO 1: Calculate and apply torque from left rocket

Here we need to insert code for calculating the torque. First, we need to know the distance from the rocket engine to the center of mass of the ship. Let’s assume our ship sprite is

$ 152x115 $, and our center of mass is at

$ <76,50> $. Thus, our r vector would be:

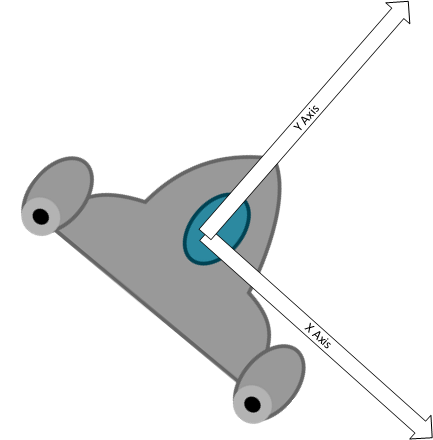

Vector2 r = new Vector2(76,50);The second value we need is our force. We could factor in our ship rotation at this point, but it is easier if we instead rotate our coordinate system and place its origin at the center of mass for the ship, i.e.:

Then our force vector is simply a vector in the upward direction, whose magnitude is the amount of the force tangential to the r vector. For simplicity, we’ll use a literal constant instead of calculating this:

Vector2 force = new Vector2(0, FORCE_MAGNITUDE);Then we can calculate the torque with the cross product of these two vectors:

float torque = force.X * r.Y - force.Y * r.X;And then calculate the rotational acceleration:

float angularAcceleration += torque / ROTATIONAL_INERTIA;The ROTATIONAL_INERTIA represents the resistance of the body to rotation (basically, it plays the same role as mass in linear dynamics). For simplicity, we could treat it as

$ 1 $ (no real effect - after all, we’re in a vacuum), which allows us to refactor as:

float angularAcceleration += torque;TODO 2: Calculate and apply torque from right rocket

Now that we’ve seen the longhand way of doing things “properly”, let’s apply some game-programming savvy shortcuts to our right-engine calculations.

Note that for this example, the vector r does not change - the engine should always be the same distance from the center of mass, and the force vector of the engine will always be in the same direction. relative to r. So the cross product of the two will always be the same. So we could pre-calculate this value, and apply the proper moment of inertia, leaving us with a single constant representing the angular acceleration from the engines which we can represent as a constant, ANGULAR_ACCELERATION. Since this is reversed for the right engine, our simplified acceleration calculation would be:

angularAcceleration -= ANGULAR_ACCELERATION * t;(and the right engine would have been angularAcceleration += ANGULAR_ACCELERATION * t;)

Thus, with careful thought we can simplify six addition operations, four multiplications, one subtraction, one multiplication, and two struct allocation operations to just two multiplications and two additions. This kind of simplification and optimization is common in game programming. And, in fact, after calculating the ANGULAR_ACCELERATION value we would probably tweak it until the movement felt natural and fun (or just guess at the value to begin with)!

Of course, if we were doing scientific simulation, we would instead have to carry out all of the calculations, couldn’t use fudge factors, and would have additional considerations. For example, if the fuel tanks are not at the center of mass, then every time we fire our rockets the center of mass will shift! That is why scientific simulations are considered hard simulations. Not so much because they are hard to write - but because accuracy is so important.