Classes and Objects

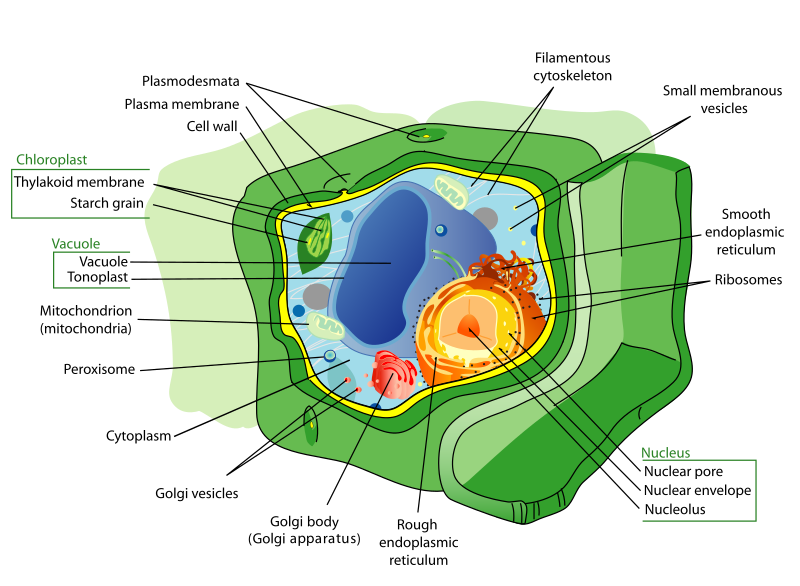

The module-based encapsulation suggested by Parnas and his contemporaries grouped state and behavior together into smaller, self-contained units. Alan Kay and his co-developers took this concept a step farther. Alan Kay was heavily influenced by ideas from biology, and saw this encapsulation in similar terms to cells.

Biological cells are also encapsulated - the complex structures of the cell and the functions they perform are all within a cell wall. This wall is only bridged in carefully-controlled ways, i.e. cellular pumps that move resources into the cell and waste out. While single-celled organisms do exist, far more complex forms of life are made possible by many similar cells working together.

This idea became embodied in object-orientation in the form of classes and objects. An object is like a specific cell. You can create many, very similar objects that all function identically, but each have their own individual and different state. The class is therefore a definition of that type of object’s structure and behavior. It defines the shape of the object’s state, and how that state can change. But each individual instance of the class (an object) has its own current state.

Let’s re-write our Vector3 struct using this concept.

public class Vector3{

public double x;

public double y;

public double z;

public Vector3(double x, double y, double z){

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.z = z;

}

public double dotProduct(Vector3 other){

return this.x * other.x + this.y * other.y + this.z * other.z;

}

public void scale(double scalar){

this.x *= scalar;

this.y *= scalar;

this.z *= scalar;

}

}class Vector3:

def __init__(self, x: float, y: float, z: float) -> None:

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.z = z

def dot_product(self, other: Vector3) -> float:

return self.x * other.x + self.y * other.y + self.z * other.z

def scale(self, scalar: float) -> None:

self.x *= scalar

self.y *= scalar

self.z *= scalarHere we have defined:

- The structure of the object state - three floating point values,

x,y, andz - How the object is constructed - the constructor that takes in parameters to set object’s initial state

- Instructions for how that object’s state can be changed, i.e. our

scale()method

We can create as many objects from this class definition as we might want. Each one will have the same behavior but different state.

Vector3 one = new Vector3(1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

Vector3 up = new Vector3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0);

Vector3 a = new Vector3(5.4, -21.4, 3.11);one: Vector3 = Vector3(1.0, 1.0, 1.0)

up: Vector3 = Vector3(0.0, 1.0, 0.0)

a: Vector3 = Vector3(5.4, -21.4, 3.11)Conceptually, what we are doing is not that different from using a compound data type like a struct and a module of functions that work upon that struct. But practically, it means all the code for working with vectors appears in one place. This arguably makes it much easier to find all the pertinent parts of working with vectors, and makes the resulting code better organized and easier to maintain and add features to. This highlights why encapsulation is one of the key concepts in object-oriented programming.