Template Method Pattern

The last pattern we’ll review in this course is the template method pattern. The template method pattern is a pattern that is used to define the outline or skeleton of a method in an abstract parent class, while leaving the actual details of the implementation to the subclasses that inherit from the parent class. In this way, the parent class can enforce a particular structure or ordering of the steps performed in the method, making sure that any subclass will behave similarly.

In this way, we avoid the problem of the subclass having to include large portions of the code from a method in the parent class when it only needs to change one aspect of the method. If that method is structured as a template method, then the subclass can just override the smaller portion that it needs to change.

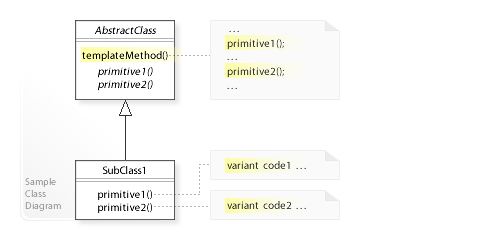

In the UML diagram above, we see that the parent class contains a method called templateMethod(), which will in part call primitive1() and primitive2() as part of its code. In the subclass, the code for the two primative methods can be overridden, changing how parts of the templateMethod() works, but not the fact that primitive1() will be called before primitive2() within the templateMethod().

Example

Let’s look at a quick example. For this, we’ll go back to our prior example involving decks of cards. The process of preparing for most games is the same, and follows these three steps:

- Get the deck.

- Prepare the deck, usually by shuffling.

- Deal the cards to the players.

Then, each individual game can modify that process a bit based on the rules of the game. So, let’s see what that might look like in code.

import java.util.List;

public abstract class CardGame {

protected int players;

protected Deck deck;

protected List<List<Card>> hands;

public CardGame(int players) {

this.players = players;

}

public void prepareGame() {

this.getDeck();

this.prepareDeck();

this.dealCards(this.players);

}

protected abstract void getDeck();

protected abstract void prepareDeck();

protected abstract void dealCards(int players);

}from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from typing import List, Optional

class CardGame(ABC):

def __init__(self, players: int) -> None:

self._players = players

self._deck: Optional[Deck] = None

self._hands: List[List[Card]] = list()

def prepare_game(self) -> None:

self._get_deck()

self._prepare_deck()

self._deal_cards(self._players)

@abstractmethod

def _get_deck(self) -> None:

raise NotImplementedError

@abstractmethod

def _prepare_deck(self) -> None:

raise NotImplementedError

@abstractmethod

def _deal_cards(self, players: int) -> None:

raise NotImplementedErrorFirst, we create the abstract CardGame class that includes the template method prepareGame(). It calls three abstract methods, getDeck(), prepareDeck(), and dealCards(), which need to be overridden by the subclasses.

Next, let’s explore what this subclass might look like for the game Hearts. That game consists of 4 players, uses a standard 52 card deck, and deals 13 cards to each player.

import java.util.LinkedList;

public class Hearts extends CardGame {

public Hearts() {

// hearts always has 4 players.

super(4);

}

@Override

public void getDeck() {

this.deck = DeckFactory.getInstance().getDeck(DeckType.valueOf("Standard 52"));

}

@Override

public void prepareDeck() {

this.deck.suffle();

}

@Override

public void dealCards {

this.hands = new LinkedList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < this.players; i++) {

LinkedList<Card> hand = new LinkedList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < 13; i++) {

hand.add(this.deck.draw());

}

this.hands.add(hand);

}

}

}from typing import List

class Hearts(CardGame):

def __init__(self):

# hearts always has 4 players

super().__init__(4)

def _get_deck(self) -> None:

self._deck: Deck = DeckFactory.get_instance().get_deck(DeckType("Standard 52"))

def _prepare_deck(self) -> None:

self._deck.shuffle()

def _deal_cards(self, players: int) -> None:

self._hands: List[List[Card]] = list()

for i in range(0, players):

hand: List[Card] = list()

for i in range(0, 13):

hand.append(self._deck.draw())

self._hands.append(hand)Here, we can see that we implemented the getDeck() method to get a standard 52 card deck. Then, in the prepareDeck() method, we shuffle the deck, and finally in the dealCards() method we populate the hands attribute with 4 lists of 13 cards each. So, whenever anyone uses this Hearts subclass and calls the prepareGame() method that is defined in the parent CardGame class, it will properly prepare the game for a standard game of Hearts.

To adapt this to another type of game, we can simply create a new subclass of CardGame and update the implementations of the getDeck(), prepareDeck() and dealCards() methods to match.